In the year since a massive shipment of ammonium nitrate exploded at Beirut port and devastated Lebanon’s capital, one of the most basic questions has proven one of the hardest to answer: Who actually owned the cargo?

Just after the blast, reporters discovered that a dormant London-registered company called Savaro Ltd had chartered the 2,750-ton shipment in 2013, intending to send it from Georgia to an explosives factory in Mozambique.

Instead, the vessel carrying it, the MV Rhosus, was detained in Beirut over unpaid debts and technical defects. The cargo sat in a warehouse until August 4, 2020, when it detonated in one of the largest non-nuclear blasts in history, killing over 200 people and displacing more than 300,000.

But figuring out just who owns Savaro has turned out to be a challenge. The company’s true shareholders are hidden behind offshore nominee directors and shareholders.

A Ukrainian businessman, Volodymyr Verbonol, who owned a company of the same name in the city of Dnipro, came under initial scrutiny. But after denying he had any connection to the Beirut shipment, he mostly escaped further attention.

An investigation by OCCRP and its partners has now proven that Verbonol was indeed behind Savaro. Following a trail of documents, journalists also found that the company was part of a larger business network that traded in technical-grade ammonium nitrate of the sort used to make explosives.

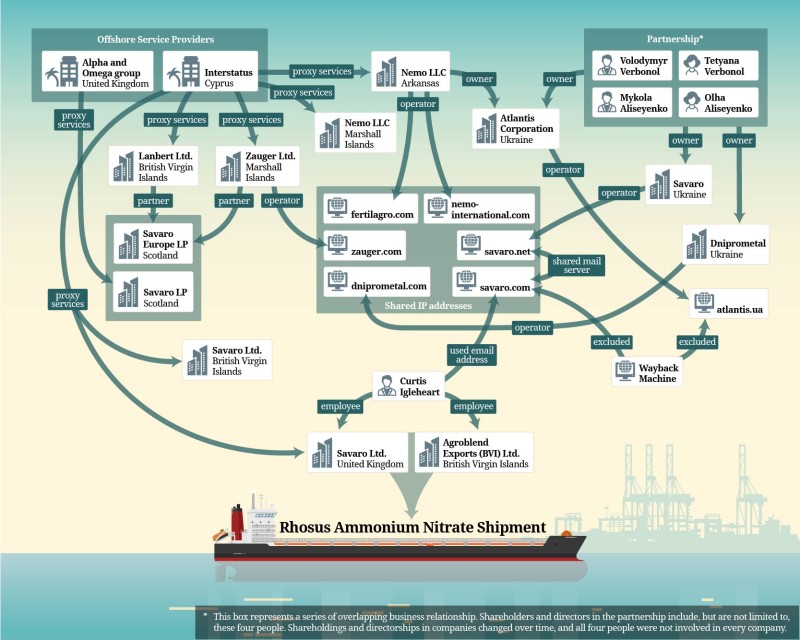

Based in Dnipro, Ukraine, the web of companies is owned and operated by a network of businesspeople including Verbonol and his father-in-law, nationally prominent construction magnate Mykola Aliseyenko. But it has disguised its operations behind at least half a dozen trade names and various strawmen and shell companies spanning England, Scotland, the Caribbean, Ukraine, the South Pacific, and the United States.

The network has sold fertilizers and chemicals to African countries since at least the 2000s. Reporters also found that the network sent at least three other shipments of ammonium nitrate to the Rhosus’ intended destination, Mozambique, in 2013. At least one Ukrainian company in the network continues to market goods online, including fertilizers. Two offshore service providers that work with clients in former Soviet republics — the Cyprus-based Interstatus and the U.K.-based Alpha and Omega group of formation agents — facilitated the network’s operations for years.

These findings paint the fullest picture yet of the people and entities behind the ammonium nitrate that exploded in Beirut. The matter may soon have legal implications, too. Last month, lawyers sued Savaro in the U.K. on behalf of the Beirut Bar Association and blast victims, arguing the company bore significant responsibility for the disaster.

The complex network behind the cargo also speaks to the sophisticated methods routinely deployed in international shipping and trade to obscure ownership, in what experts say is often a deliberate attempt to evade liability and facilitate criminal or other underhanded business practices.

People leaving Beirut after a catastrophic explosion that destroyed much of the city’s northern neighbourhoods.

Camille Abousleiman, the lead lawyer in the London case against Savaro, said the company shared responsibility for the explosion because it was the legal owner of the cargo and failed to take proper measures to retrieve the dangerous materials. He said he hoped the case against the company would be the first step in holding all those responsible for the disaster to account.

“Savaro and the people that control it have a responsibility to ensure that their cargo is stored properly and is not a risk to people,” Mark Taylor, Senior Analyst at The Docket, an initiative of the Clooney Foundation for Justice, told OCCRP.

“It’s not okay, under the international human rights regime, to just dump dangerous chemicals in a warehouse and walk away.”

Mark Taylor

Senior Analyst, The Docket

“It's not okay, under the international human rights regime, to just dump dangerous chemicals in a warehouse and walk away.”

In a statement sent to reporters, the Ukrainian companies denied any involvement in the Rhosus shipment, and laid the blame for the Beirut blast on Lebanese authorities.

“The entire time, the line of business of Atlantis Corporation, Savaro and Dniprosoft has been IT: the production of software and Internet marketing,” the statement said, referring to the names of three Ukrainian companies in the network.

Online advertising for other goods, such as fertilizers, was done on behalf of their clients and was “posted by employees, and often interns, who may not have fully understood that our company was acting on behalf of the manufacturers,” they said.

Savaro’s British lawyer, Richard Slade, did not respond to a request for comment.

A Lack of Accountability

Sea Shells

The Rhosus was chartered and its cargo was purchased by two companies from the Savaro network: the London-registered Savaro Ltd, and another called Agroblend Exports (BVI) Ltd in the British Virgin Islands.

Documents Show How Savaro and Agroblend Were Linked to Beirut Cargo

On paper, neither company was tied to anyone in Ukraine. Agroblend’s owners and directors are hidden behind the British Virgin Islands’ strict secrecy. Savaro’s true ownership was obscured by nominee services provided by Interstatus, the Cyprus-based corporate services provider.

Interstatus provided nominee services for at least four companies bearing the Savaro name. One, a Scottish limited partnership that declared itself a fertilizer trader, had paperwork filed jointly by subsidiaries of Interstatus and Alpha and Omega group, a U.K.-based network of corporate service providers that has been flagged for working for sanctioned individuals and alleged money launderers.

The Savaro network.

Transparency International U.K. sent a report on Alpha and Omega to U.K. revenue authorities last year urging an investigation, but have so far received no official response, the group’s investigations lead Ben Cowdock told OCCRP.

“In terms of the amount of companies that have gone on to be used in suspicious activity, [Alpha and Omega are] definitely one of the most prolific,” Cowdock said.

Interstatus is currently under investigation by the Cypriot financial regulator, CySEC, outgoing chairwoman Demetra Kalogerou told OCCRP.

Interstatus’ owner, Marina Psyllou, told OCCRP that her company had conducted full know-your-customer checks on all clients, but that she could not share the names of the true owners with third parties.

The U.K. company Savaro Ltd “to the best of our knowledge and belief was always dormant and it had always been presented to us as such by our client,” she said.

The head of Alpha and Omega, Aleksej Strukov, declined to comment on their clients but said his company works with Interstatus, providing addresses and mail forwarding services.

Savaro and Syria Suspicions

An International Trail

Reporters were able to tie Savaro Ltd. and Agroblend Exports (BVI) Ltd. to Verbonol’s network thanks to clues found in a series of emails sent by a company representative after the Rhosus was detained in Beirut.

In December 2013, an Agroblend representative calling himself Curtis Igleheart contacted a Lebanese businessman to help him retrieve the ship’s cargo, which he identified as “dangerous."

Igleheart complained that his company was blindsided when the ship’s operator, Teto Shipping, made unannounced stops in Greece and Beirut, where the Rhosus was eventually impounded.

Teto Shipping said it was too broke to continue to Mozambique’s Beira port even though it had been paid the full cost of the shipping, nearly $375,000, Igleheart wrote. He accused the operator of shaking down his company for more money.

“Presently the vessel is still [in] Beirut and vessel owners say they couldn’t load cargo in Beirut and they don’t have money to pass for Beira. They started blackmailing us to pay additional 180.000USD (otherwise we will never see our cargo).”

Nearly a year later, Igleheart reached out again to the same businessman. But now, instead of representing Agroblend, his emails were sent from a savaro.com account.

Emails from Agroblend and Savaro Domains

Although the domain’s ownership was hidden by online anonymization services, reporters found that savaro.com shared an email server with the website of the Ukrainian branch of Savaro. It also shared an I.P. address used by the Ukraine branch of Savaro, as well as with other sites linked to offshore companies in the network that advertised fertilizers and other chemicals in Latvia and the United States.

Igleheart also played a role in Savaro’s efforts to hire a Lebanese lawyer, Joseph Kareh, to inspect the ammonium nitrate in 2015. After that, the company appears to have stopped trying to recover its cargo. Savaro paid Kareh from an account in its name at the Cyprus branch of Ukrainian-owned Privatbank.

Reporters were unable to identify an employee named Igleheart in company records or reach a U.K. number he previously used.

A Fertile Market

Volodymyr Verbonol was born in 1959 and came up through the business and political circles of Dnipro, an industrial city in central Ukraine.

He worked as an assistant for prominent Ukrainian trade union leader Mykhailo Volynets and later for Denys Dzenzersky, a former member of parliament with whom he had also partnered in business.

In 2001, Verbonol set up a business called Atlantis Corporation, which marketed fertilizers and other products, according to fragments of a now-deleted webpage retrieved by reporters. Verbonol was the company’s public face.

With partners including the construction magnate Aliseyenko, Verbonol soon established several companies marketing goods and services including fertilizers, metallurgical equipment, software, and web design. One of them was the Ukrainian branch of Savaro, established in 2009.

Linked to these Ukrainian companies was a web of offshore shell companies, most of which were run by Interstatus, company registry documents show. They included companies under the Savaro name in Scotland, England, and the British Virgin Islands, as well as other related holding companies in the Marshall Islands and the United States.

The interior of a building in Dnipro, Ukraine, used by Savaro network companies.

New Ammonium Nitrate Shipments Revealed

Verbonol’s Ukraine-based Atlantis Corporation shut down in 2011 after declaring bankruptcy, but other companies in the network kept operating.

The same year, web administrators contacted the Internet Archive, a nonprofit digital archive which backs up old websites through the Wayback Machine, and asked them to remove records of two of its main websites, savaro.com and atlantis.ua, Wayback Machine director Mark Graham told OCCRP.

Reporters were able to recover fragments of Atlantis Corporation’s prior website that were crawled by a third party site, the translation service Linguee. They show that the company advertised fertilizers and publicly declared Verbonol as its president. A snapshot of savaro.com still available online shows a list of agricultural chemicals , including ammonium nitrate.

A screenshot of an archived version of one of Atlantis Corporation’s websites, from 2004, shows the company marketing fertilizer.

Verbonol and his partners’ Ukrainian companies appear to have stopped advertising fertilizer online under their own names after this point. Savaro in Ukraine began to present itself as a seller of machinery and equipment, and, later, a software and web development services provider. However, the websites linked to the offshore structure continued to market chemicals.

A former Savaro network employee, who worked for the Ukrainian companies around the time of the Rhosus shipment, told OCCRP he saw little evidence they were doing IT work, and that fertilizer sales remained the main part of their business.

“I hardly remember anyone who could be connected to software. There were no IT guys or software developers,” said the former employee, who asked not to be named out of concern for his safety.

Reporters also learned that, the same year as the Rhosus shipment, Savaro also sent over 17,000 metric tons of ammonium nitrate in three separate shipments to Beira, Mozambique. The Rhosus had also been destined for Beira before being detained at Beirut’s port.

The same Mozambican company that was meant to receive the Rhosus cargo, Fábrica de Explosivos de Moçambique, told OCCRP that it had purchased two other shipments from Savaro in 2013, amounting to nearly 11,000 metric tons of technical grade ammonium nitrate, which is typically used to make explosives.

Fábrica de Explosivos de Moçambique spokesman Antonio Cunha Vaz said that as far as he knew, Savaro was a Ukrainian company whose boss was known to him simply as “Mr. Volodymir.”

Savaro’s sister company, Agroblend, also sent a third shipment of 6,500 tons of ammonium nitrate from Ukraine and Croatia to Beira, which arrived in August 2013, according to MUR Shipping, the Netherlands-based operator of the ship that carried it. It is unclear who purchased this third shipment. Cunha Vaz said his company was not the customer.

A red plume rises from Beirut’s port following last year’s explosion.

Disappearing Acts

With legal action looming in London, the owners of Savaro appear to be moving to cover their tracks.

On August 23, the company’s ownership was transferred to a Ukrainian lawyer named Volodymyr Hliadchenko. Ukrainian records show that Hliadchenko is the apparent nominee owner of at least a dozen local companies, including at least one at the same address where the Ukraine branch of Savaro is located.

Reached by phone, Hliadchenko said he had been looking to buy a London company and had selected Savaro at the suggestion of other Ukrainian lawyers. He said the company was not to blame for the Beirut disaster.

The network also may have attempted to hide the fact that they were continuing to sell chemicals.

In July, reporters found a website advertising fertilizer and other materials{:target="_blank:} under the name Dniprometal, the same name as a company set up in July 2011 by Verbonol and Olha Aliseyenko — whose patronym, Mykolaivna, indicates she may be Mykola Aliseyenko’s daughter.

At the time, the site listed a Dnipro office address used by the company and other Savaro network firms. It also shared an I.P. address with several linked companies.

In their response to OCCRP, Verbonol and partners said Dniprometal had never conducted any business, including trading fertilizers.

Shortly after, reporters found that the Dnipro office address used by Savaro companies had been removed from the website and replaced with the official registry number and address of a separate company, which was also called Dniprometal but was owned by different people and had shut down over a decade ago.

Reporters sent a follow-up email to Verbonol and partners, asking them if they had changed the website in order to deceive reporters or plaintiffs in the London lawsuit.

They did not respond.

Graham Stack (OCCRP), Rana Sabbagh (OCCRP), Aleksey Kovalev (Meduza), Nino Bakradze (ifact.ge), and Sarunas Cerniauskas (OCCRP) contributed reporting.

CORRECTION: This story was updated to reflect the fact that Denys Dzenzersky is no longer wanted by Ukraine’s National Anti-Corruption Bureau. His case was dropped in late 2020 after the country’s Constitutional Court nullified the article of the criminal code under which he was being investigated.