Since the devastating explosion of a store of ammonium nitrate in Beirut’s port on August 4, Lebanese citizens have taken to the streets in shock, outrage, and grief.

Above all, they have demanded answers: Where did the nearly 3,000 tons of explosive chemicals come from, and who owned it? Why did the rickety ship that brought the hazardous material to Lebanon end up stranded in the city’s port in late 2013? And how could the impounded chemicals sit for over half a decade in an unsafe warehouse before tragedy finally struck?

In Lebanon itself, the causes of the disaster appear to be tied to bureaucratic ineptitude. Just two weeks before the warehouse exploded, Lebanon’s president received an urgent report from the country’s security services warning him that the situation was critically dangerous.

The international side of the affair, on the other hand, quickly became lost in a maze of corporate and financial intrigue. Igor Grechushkin, the Russian man variously described as the owner or the operator of the Moldovan-flagged MV Rhosus, is said to have abandoned the vessel in Lebanon after declaring bankruptcy. The vessel’s deadly cargo had been purchased from the country of Georgia by a Mozambican firm that produces commercial explosives, via a British middleman trading firm linked to Ukraine.

The ownership of the Rhosus, and the companies that ordered the nearly 3,000 tons of ammonium nitrate to be transported halfway around the world in a rickety ship, are obscured by layers of secrecy that have stymied journalists and officials at every turn. Even the Lebanese government does not appear to know who actually owned the ship.

But an international team of investigative journalists has uncovered new facts about the lead-up to the explosion, which killed at least 182 people, injured over 6,000 and caused hundreds of thousands to lose their homes.

Reporters found that the circumstances for the tragedy were set in the baffling nowhere-world of offshore trade, where secretive companies and pliant governments allow questionable actors to work in the shadows.

Among those secretly connected to the Rhosus and its final voyage: a hidden shipping tycoon, a notorious bank, and businesses in East Africa previously investigated for ties to the illicit arms trade.

In their joint investigation spanning ten countries, reporters found that:

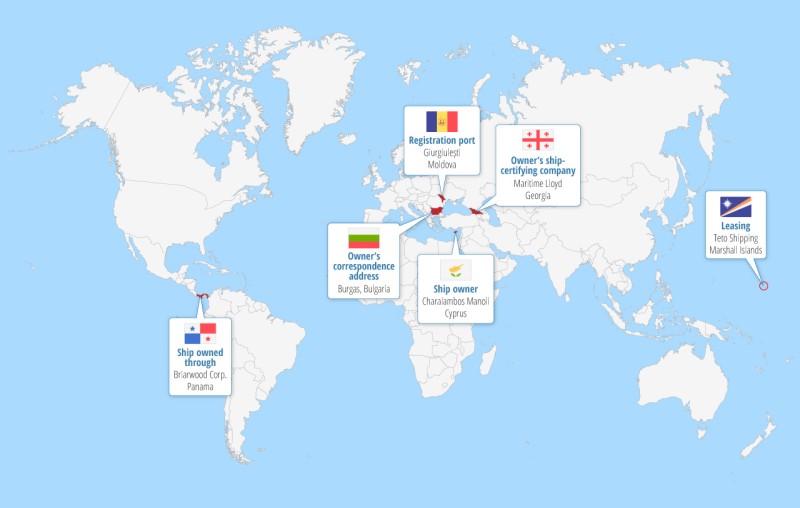

Igor Grechushkin did not own the Rhosus but was merely leasing it through an offshore company registered in the Marshall Islands. Instead, documents show that the true owner of the Rhosus was Charalambos Manoli, a Cypriot shipping magnate. Manoli denies this, but declined to provide documents to back up his claim.

Manoli owned the ship through a company registered in the notoriously secretive jurisdiction of Panama, which received its mail in Bulgaria. He registered it in Moldova, a land-locked Eastern European country that is notorious as a jurisdiction with lax regulations for vessels that fly its “flag of convenience.” To do this, he worked through another of his companies, Geoship, one of a handful of officially recognized firms that set foreign owners up with Moldovan flags. Then, yet another Manoli company, this one based in Georgia, certified the ship as seaworthy — even though it was in such bad shape it was impounded in Spain days later.

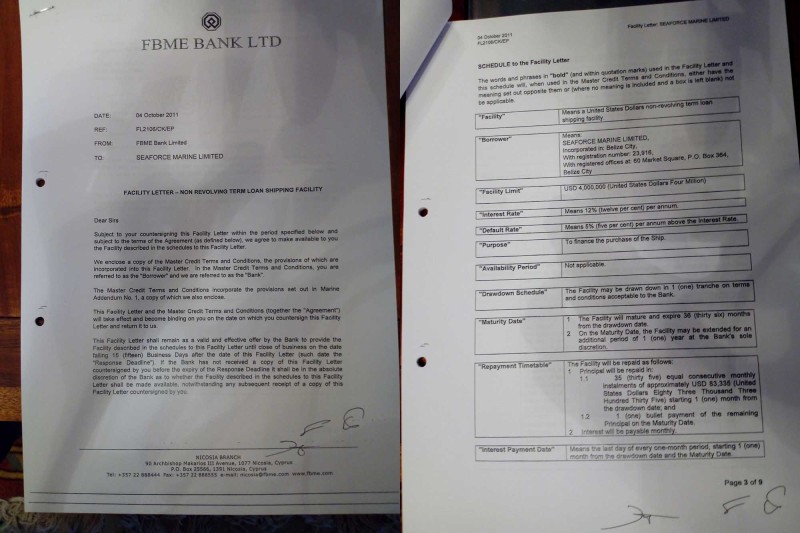

At the time of the Rhosus’ last voyage, Manoli was in debt to FBME, a Lebanese-owned bank that lost multiple licenses for alleged money laundering offenses, including helping the Shia militant group Hezbollah and a company linked to Syria’s weapons of mass destruction program. At one stage, the Rhosus was offered up as collateral to the bank.

The ultimate customer for the ammonium nitrate on the ship, a Mozambican explosives factory, is part of a network of companies previously investigated for weapons trafficking and allegedly supplying explosives used by terrorists.The factory never tried to claim the abandoned material.

The intermediary for the shipment, a British company that was dormant at the time, convinced a Lebanese judge in 2015 to get the ammonium nitrate tested for quality with the intent of claiming it. The stockpile was found to be in poor condition, and the company, Savaro Limited, did not try to take back the ammonium nitrate in the end.

The new revelations show how, at almost every stage, the Rhosus’ deadly shipment was connected to actors who used opaque offshore structures and lax government oversight to work in the shadows.

The revelations also expose the particular dangers posed by the lack of transparency in the maritime shipping industry, according to Helen Sampson, the director of Cardiff University’s Seafarers International Research Centre.

The findings “highlight all the weaknesses of the [maritime shipping] system and how they can be exploited by those who want to exploit them,” Sampson said.

The Rhosus’ True Ownership

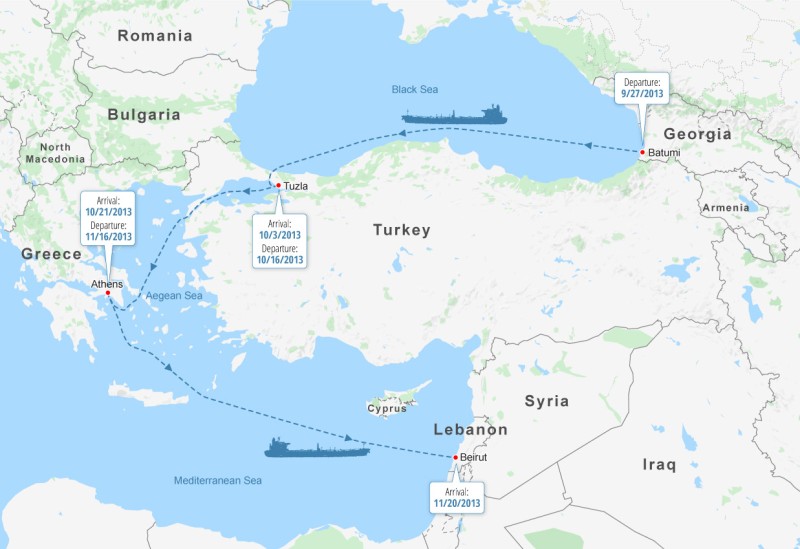

The Moldova-flagged ship that set out from the Georgian port of Batumi in September 2013, carrying over 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate made by a local factory and bound for Mozambique, was in poor shape. The decks were corroded, it lacked auxiliary power, and had problems with radio communication. The vessel stopped in Beirut to pick up more cargo and never left. It was detained first by creditors seeking debts from its operator, and later by port officials who considered it unsafe to sail.

After the ship was abandoned and impounded in 2014, leaving Ukrainian and Russian crew members stranded on board for 10 months, the ammonium nitrate was moved to a warehouse at the port. The ship eventually sank behind a breakwater, where its wreckage remains.

Following the Beirut explosion, media reports and government authorities have focused on one man as responsible for abandoning the ship and its cargo: Igor Grechushkin. A 43-year-old Russian citizen living in Cyprus, Grechushkin has been repeatedly identified as the Rhosus’ owner. He has avoided all attempts by OCCRP and other outlets to speak to him, although he was interviewed by Cypriot police at the request of Lebanese authorities on August 6.

The Ship Owner Who Wasn’t

Igor Grechushkin has attracted attention around the world for his role in the Lebanon explosion. But public records suggest that he has a history of acting as a corporate officer in companies run by others. He was also convicted of aggravated theft in the mid-2000s in Russia’s far east, for reasons that remain unclear.

But Grechuskin, on paper at least, did not own the Rhosus. Instead, through a company in the Marshall Islands called Teto Shipping, he had chartered the ship from a company in Panama, Briarwood Corporation, according to official records from Moldova’s Naval Agency.

Panama, a notoriously secretive offshore jurisdiction, does not make public the ownership of companies registered there. But by searching through court records in Cyprus, OCCRP journalists found a 2012 document showing that Briarwood belonged to Manoli.

Three of Manoli’s other companies helped the Rhosus obtain its Moldovan flag, issued its seaworthiness certificates, and provided intermediary services that helped keep the ship at sea though it was riddled with serious defects.

Manoli’s connection to the Rhosus did not stop there. Records show that another of his companies, Geoship Company SRL, was responsible for officially registering the ship in Moldova, which has notoriously lax regulations for transparency, safety, and crewing.

The Mysterious Manoli

Charalambos Manoli was born in 1960 in Famagusta, a coastal city in what is now the Turkish-controlled part of Cyprus. After studying shipbuilding in Scotland, he returned to Cyprus to work as a ship inspector, and went on to found multiple shipping companies.

A Georgian company then owned by Manoli, Maritime Lloyd, acted as the ship’s “classification society” — a body responsible for certifying that ships are seaworthy. The company was sold in 2019.

In late July 2013, Maritime Lloyd issued a certification claiming the Rhosus had been safely constructed, inspection records show. But just days later, port inspectors in Seville detained the ship, citing 14 defects, including problems with its auxiliary power system.

Solving that latter problem was key to getting the Rhosus back at sea one last time — and it was another of Manoli’s companies that did it. In August 2013, two months before the ship set off on its final voyage from Batumi, Manoli’s Cypriot ship management company, Acheon Akti acted as an intermediary to rent a new generator from international equipment rental firm Aggreko, a company representative said by email. The unpaid hiring cost for this generator would become one of the debts that stuck the Rhosus at the Beirut port.

According to Cardiff University’s Sampson, the complex web of companies around the Rhosus was typical of those used to minimize costs and shield owners from accountability.

“If you’re sailing a ship that you know is unseaworthy then you have an incentive to hide your identity,” Sampson said.

“The fact that it appears that the owner of the Rhosus actually owns the classification society which issued the ship with its certificate of seaworthiness — I’d say that means that the certificate isn’t worth anything, really.”

A Debt to a Dirty Bank

In a series of interviews, Manoli gave reporters changing accounts of the ship’s ownership. He initially claimed that his Panama company, Briarwood, had sold the ship to Grechushkin’s Teto Shipping in May 2012.

When later presented with documents that showed Briarwood still owned the ship — and that it had merely been leased to Teto Shipping — Manoli revised his statement. He acknowledged that Briarwood had indeed leased the Rhosus to Teto Shipping in 2012. But he claimed that later, in August 2013, just before the ship’s last voyage, he had transferred all the shares in the Panama company to Grechushkin, making the Russian the effective owner of the ship.

Manoli agreed to allow reporters to view documents showing a share transfer or a contract of sale, but subsequently refused reporters’ attempts to set up a video call to do this.

Manoli also sought to distance the ship’s owner — who he claimed was Grechushkin — from culpability in the explosion.

“The cargo went to Lebanon in 2013. Not now. They confiscated the man’s ship over there. And he declared bankruptcy because of the confiscation of the ship,” he said by phone. “Given this, what’s the responsibility of this man if Lebanese authorities didn’t properly store this fertilizer?”

Manoli denied there was any conflict of interest in his operating the companies that helped register and certify the Rhosus.

Registry documents also show that the Panama company that owned the Rhosus, Briarwood, maintained its mailing address at a now-defunct company in Bulgaria, named Interfleet Shipmanagement. The owner, Nikolay Petrov Hristov, confirmed that the company was a junior partner of a Cypriot firm of the same name owned by Manoli.

Hristov claimed he froze the Bulgarian company in 2012 after Manoli got him involved with the Sakhalin’s FBME loan without his knowledge.

Manoli, however, said that Bulgaria’s Interfleet Management had nothing to do with Sakhalin other than “technical management.”

One Last Stop

While OCCRP’s investigation shows that Grechushkin didn’t own the Rhosus, he was involved in much of the vessel’s direct operation. The ship’s captain at the time of its last journey, says Grechushkin personally ordered him to dock the Rhosus in Beirut on its way to Mozambique.

The stated reason for the last-minute stop, according to the captain, Boris Prokoshev, was to pick up trucks and other cargo in order to pay for passage through the Suez Canal. But the plan was scrapped after the first truck loaded onto the vessel almost damaged its deck, Prokoshev said.

This account is backed up by a document obtained from Lebanon’s Ministry of Public Works and Transport.

Grechushkin soon abandoned the ship. Captain Prokoshev and three crew members, however, would spend the next 10 months trapped aboard the vessel by Lebanese authorities as creditors pursued Grechushkin for his debts. Lebanese inspectors who boarded the vessel in April 2014 said the crew had almost no food or money, and garbage was piling up on deck.

Correspondence held by Lebanese authorities show that on at least one occasion, in March 2014, Grechushkin did try to rescue the crew. Captain Prokoshev, however, complained soon afterwards that Grechushkin’s company had stopped paying their salaries and was avoiding all communication with them.

Lebanese authorities and the ship’s creditors apparently had no idea that Manoli was the owner of the ship. Neither Manoli nor his companies are mentioned in any Lebanese court documents obtained by reporters. Nor is there any indication that any attempt was made to contact him.

The Mozambique Connection

The owners of the Mozambican factory that ordered the ammonium nitrate did not attempt to retrieve the cargo after the Rhosus was seized.

Documents obtained by OCCRP show that the factory, Fabrica de Explosivos de Mocambique, is part of a network of companies with connections to Mozambique’s ruling elite. The companies had been investigated for illicit arms trafficking and supplying explosives to terrorists.

The factory is 95-percent owned by the family of the late Portuguese businessman Antonio Moura Vieira, through a company called Moura Silva & Filhos.

In an email, Antonio Cunha Vaz, a spokesman for Fabrica de Explosivos, said it had ordered the ammonium nitrate through Savaro Limited. When the shipment never arrived in Mozambique, they simply placed another order.

Moura Silva & Filhos was previously investigated for allegedly supplying explosives used in the 2004 train bombings in Madrid that killed almost 200 people. The following year, after receiving a tip from Spanish authorities, Portuguese police raided four warehouses belonging to the company, seizing 785 kilograms of explosives allegedly concealed from its inventory system.

The company is also linked to Mozambique’s first family and military. Fabrica de Explosivos’ current head, Nuno Vieira, has since 2012 been the business partner of Jacinto Nyusi, the son of Mozambican President Filipe Nyusi, with whom he owns an events and marketing company.

The same year, Vieira, together with Mozambican state investment company Monte Binga and the country’s secret service, founded Mudemol, a munitions and explosives manufacturer that supplied the military. Filipe Nyusi was the minister of defense at the time. Monte Binga has since been flagged by the United Nations for allegedly breaking international sanctions by involving itself in military deals with North Korea.

The explosives factory that was meant to receive the Rhosus’ cargo also shares an address with ExploAfrica, a company co-owned by the Vieira family. Confidential corporate and government documents shared by the Conflict Awareness Project, a U.S.-based nonprofit, show that ExploAfrica and its affiliates were investigated by South African and Portuguese authorities for obtaining U.S. and Czech weapons that later ended up in the hands of rhino and elephant poachers in South Africa’s Kruger National Parks on the border with Mozambique.

A South African front company that was allegedly used to buy the weapons, Investcon, is closely tied to Maputo-based Bachir Suleman, designated by the US government as an alleged “drug kingpin”.

In an email, Antonio Cunha Vaz, a spokesman for Fabrica de Explosivos, said that staff members from Moura Silva & Filhos were interrogated by police but were cleared of any wrongdoing. He said the company’s business links to the Mozambican president’s son were transparent, and denied any connection to alleged drug kingpin Suleman.

“All the deals made by ExploAfrica were perfectly legal and ...If there was any use of weapons for purposes not complying to the law, ExploAfrica is not responsible for them,” Cunha Vaz added.

The Middleman

While the Mozambican factory made no apparent effort to claim the material, another company did: the trading firm that acted as a middleman in the deal.

Company records show that the middleman, United Kingdom-based Savaro Limited, ordered the ammonium nitrate at a time when it reported no official business activity to U.K. authorities. It has remained dormant since.

Savaro Limited is linked to another company called Savaro in the Ukrainian city of Dnipro, via a series of shareholders and directors in Cyprus and the United States. The Ukrainian company’s director is Vladimir Verbonol, a local businessman. He told OCCRP he had no connection to the shipment.

Court documents show that Savaro in February 2015 hired a Lebanese lawyer to petition a local court to inspect the quality and quantity of the ammonium nitrate then being held in the port warehouse. That expert report concluded that most of the one-ton bags containing the ammonium nitrate — approximately 1,900 — were ripped and had their contents spilling out.

The documents show that Savaro declined to carry out chemical testing of the ammonium nitrate, and there is no record of the company attempting to recover the material after that point.

In Savaro’s place, a new potential buyer was sought for the dangerous stockpile.

First the Lebanese Customs Department asked the country’s army to take it, but they refused, instead suggesting that it be offered to a local manufacturer, Lebanese Explosives Co, owned by businessman Majid Shammas. There is no record of the company accepting the offer.

The army then suggested simply sending the ammonium nitrate back to Georgia at the expense of the importer. This, too, never happened, for reasons that remain unclear.

By February 2018, Lebanese authorities appear to have given up on their efforts to offload the ammonium nitrate.

But the stockpile remained in an unsecured warehouse — an explosion waiting to happen.

In a July 20, 2020, report to the president and prime minister — just two weeks prior to the explosion — Lebanese security services warned that there were serious security flaws at the facility that left the ammonium nitrate open to theft.

One door of the unguarded warehouse was missing, while there was also a hole in the southern wall, the report said.

“In case of theft, the thief could turn these goods into explosives,” the report warned.

According to three European intelligence sources investigating the blast, who spoke to reporters on the condition of anonymity, the amount still stored in the warehouse by August may have been smaller than the initial 2,750 tons. They said the size of the explosion was equivalent to as little as 700 to 1,000 tons of ammonium nitrate.

But the blast was big enough to destroy large parts of eastern Beirut. It was one of the strongest non-nuclear explosions ever recorded.

Reporting by Aubrey Belford, Rana Sabbagh, Stelios Orphanides, Sara Farolfi, Eli Moskowitz, Sarunas Cerniauskas, Antonio Baquero, Riad Kobeissi, Diana Mukalled , Eman Qaisi, Giannina Segnini, Ana Poenariu, Atanas Tchobanov, Assen Yordanov, Ion Preasca, Yanina Korniienko, Karina Shedrofsky, Khadija Sharife, Nino Bakradze, Aderito Caldeira, Juliet Atellah, Alexey Kovalev, Fritz Schaap, and Christoph Reuter.

This story was produced in collaboration with Daraj.com (Lebanon), ARIJ.NET (Jordan), Meduza (Russia), iStories (Russia), Der Spiegel (Germany), RISE Moldova, RISE Romania, Bivol (Bulgaria), ifact.ge (Georgia), aVerdade (Mozambique)