A company tied to Lebanon’s central bank governor bought a stake in his son’s company, then sold it to a major Lebanese bank that he regulates, OCCRP and Daraj.com have learned.

These findings raise questions about whether the deal represented a conflict of interest for controversial Banque du Liban (BdL) Governor Riad Salame, whose extensive offshore real estate investments were the subject of an investigation published in August by OCCRP and Daraj.com, its partner in Lebanon.

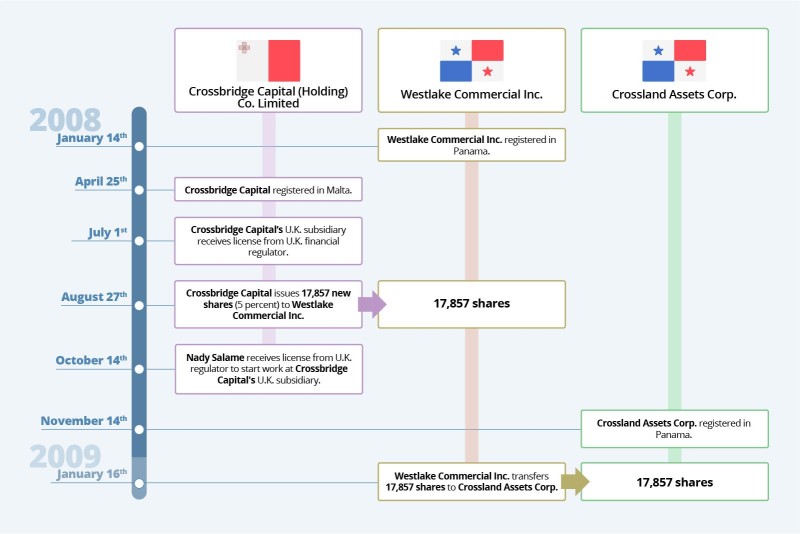

The transaction involved shares in Crossbridge Capital, a London wealth management firm, that were held by an obscure Panama-registered company, Crossland Assets Corp. Salame’s son, Nady, formerly worked for Crossbridge and retains shares in his old firm.

Bank Audi, Lebanon’s largest bank, acquired the Crossland shares in 2016, as Riad Salame was instituting a controversial monetary policy that benefited the bank to the tune of $1.6 billion.

Who was behind Crossland Assets? It is impossible to say because its ownership is shielded by corporate secrecy laws. But there are clues tying it to Riad Salame.

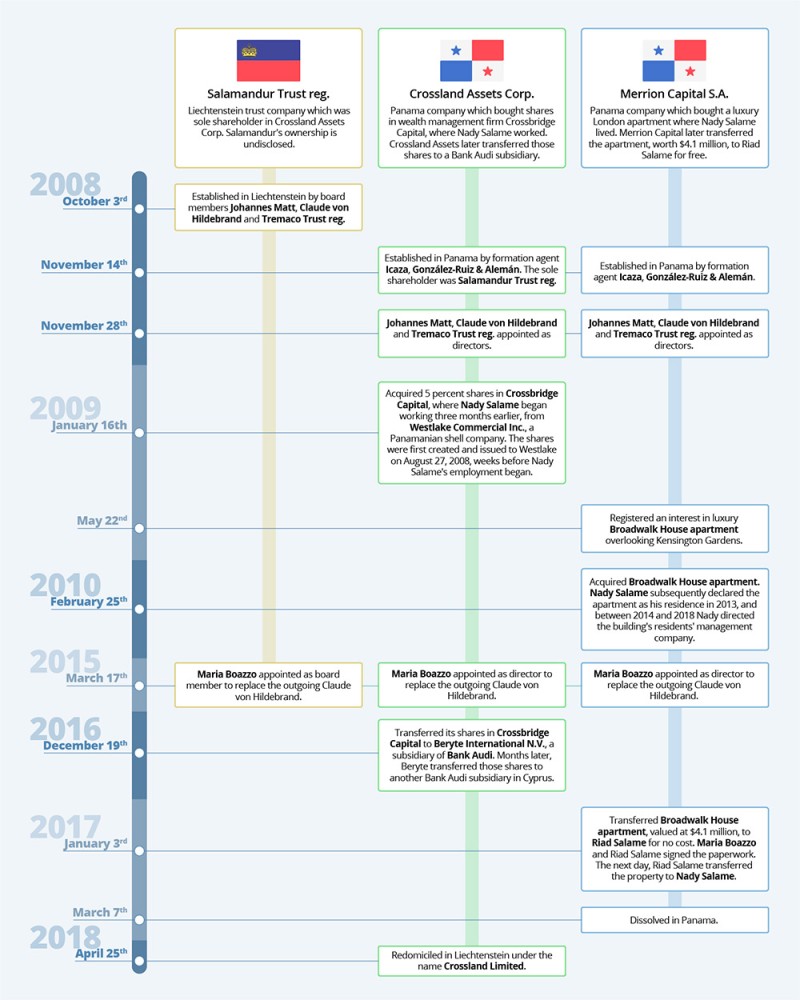

Crossland was set up on the same day in 2008 and placed under the same management as another Panamanian company, Merrion Capital S.A., that gave Riad Salame a luxury apartment in London. The same group — two directors, two subscribers, an agent, and a treasurer — also managed Crossland’s sole shareholder, a Liechtenstein trust company.

Crossland was only two months old when it acquired the Crossbridge Capital shares, suggesting it was established for the purpose of buying them from another Panama shell company, Westlake Commercial Inc. Westlake’s ownership, and the terms of the transfer to Crossland Assets, are unknown.

Westlake, which has reported no other business activity, previously paid Crossbridge Capital $2.5 million for about 5 percent of the company.

Under Lebanese law, the Central Bank governor is prohibited from engaging in outside business beyond holding securities or shares in joint stock companies.

Ali Zbeeb, a Beirut-based lawyer and expert in international banking and financial regulation, told OCCRP that violating the prohibition would be considered a conflict of interest that could prompt removal from office.

No public records show a direct link between Riad Salame and Crossland Assets, nor is there direct evidence that he broke the law. However, OCCRP’s findings raise serious questions the powerful governor has refused to address.

OCCRP asked Salame three times over four months if he held an interest in Crossland Assets. Each time he deflected or ignored the question.

“We fail to understand this question,” he said through his attorney. He said OCCRP should contact Crossbridge Capital, which cited EU confidentiality directives in declining comment.

When asked again about Crossland Assets, Salame responded, “Any private matter is not open for discussion.” When asked about Westlake, Salame responded, “We have not identified any matter of public interest in your email... Consequently, we have nothing more to address in this communication.”

Lebanon’s Offshore Governor

The Apartment

A key piece of evidence tying Riad Salame to Crossland Assets is a luxury apartment in London where his son, Nady, lived for years.

Before joining Crossbridge Capital in 2008, the younger Salame interned in the London operation of Credit Suisse, whose former directors founded Crossbridge Capital and made him one of their first hires.

In 2009 Merrion Capital filed papers to register an interest in a luxury apartment just across Hyde Park from Crossbridge Capital’s office in Mayfair. Merrion Capital bought the apartment outright in 2010. Nady Salame declared it his residence in corporate documents in 2013.

On January 3, 2017, Merrion Capital transferred the apartment, valued at $4.1 million, to Riad Salame, who signed a statement saying the transaction was “not for money or anything that has a monetary value.” The next day he gave the apartment to his son.

This series of events suggests Riad Salame received a large gift from an unknown party or that he owned or controlled Merrion Capital, which was dissolved two months later. He did not respond at all when OCCRP asked about this company.

Nady Salame, who still owns the apartment, did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

The Shell Game

Crossland Assets, the Panama company linked to Merrion Capital, moved to Liechtenstein in 2018. It reported $42.8 million in cash assets and $1.8 million in portfolio investments in December 2019.

Since its creation, Crossland Assets has been owned by a Liechtenstein trust, which is not required to file public information about its shareholders.

But the trust has a familiar name: Salamandur Trust reg.

Riad Salame did not respond when asked if he held an interest in Salamandur, or whether its name was derived from his own. But at least once in the past he appears to have been inspired by family names in creating legal entities.

What’s in a Name?

Salamandur was established in October 2008 with three board members: Johannes Matt, a former member of Liechtenstein’s parliament; Tremaco Trust reg., Matt’s professional trust services company; and Claude von Hildebrand.

A month later, the same three directors were appointed to run Crossland Assets and Merrion Capital.

Von Hildebrand resigned all three directorships in early 2015 and was replaced by Maria Boazzo, another trust professional based in Switzerland. All three trust professionals were associated with a tax evasion scheme that led to a record $2.6 billion fine in 2014 for Credit Suisse in the United States.

Questionable Associations

The same trust professionals who manage offshore shell companies tied to Riad Salame participated in a trust business involved in a tax evasion scheme that led to a record $2.6 billion fine for Credit Suisse in the United States.

Conflict of Interest

Beirut-based Bank Audi’s operations are regulated by and highly dependent on the policies of Lebanon’s Central Bank, which has been run by Riad Salame since 1993.

Bank Audi in recent years has benefited from so-called “financial engineering,” an unconventional monetary policy Salame introduced in 2016. The policy involved complex and opaque deals that enabled commercial banks to profit from swapping dollars for local currency, at a premium.

While financial engineering benefited all banks, the Banking Control Commission of Lebanon determined that Bank Audi saw the biggest profit from it — some $1.6 billion in 2016 alone.

Bank Audi became a major investor in Crossbridge Capital through deals structured in a way that obscured its association with Crossland Assets.

A subsidiary, Banque Audi Suisse S.A., agreed to acquire about 19 percent of Crossbridge Capital in December 2014. The deal was valued at about $9.5 million, but it didn’t close until September 2015 — about a month after Nady Salame stopped managing money for Crossbridge clients.

Crossbridge also received a $14.5 million general purpose loan from Beryte International N.V., an obscure and largely inactive Bank Audi subsidiary registered in Curaçao.

In December 2016, Beryte International also acquired the Crossbridge Capital shares held by Crossland Assets. Terms of that deal are unknown, but the shares were valued at $2.06 million when they were transferred to yet another Bank Audi subsidiary six months later.

A Lebanese attorney who specializes in public policy law questioned the deals in light of Riad Salame’s apparent ties to Crossland Assets.

“The occurrence of transactions between [Crossland and Beryte] indicates conflict of interest represented by commercial dealings and maybe indirect participation in the operation of Audi Bank and its activities,” Nizar Saghieh, co-founder of the Beirut-based legal reform advocacy group Legal Agenda, told OCCRP and Daraj.com.

“Audi Bank is a financial institution which is under the supervision of Riad Salame, and of which he is banned to participate in through any form or shape during his work,” Saghieh added.

Mohammad F. Mattar, a Lebanese lawyer known for his work on cases involving corruption and financial crime, agreed with Saghieh.

In a letter to Daraj.com, Mattar described the use of offshore trusts and corporations as “a contrived and concocted corporate shielding meant not to be easy to pierce. ...This structure in itself uncovers the intention to hide, or at best obscure the transactions that were carried out.

“The design that comes out looks more like a cover-up scheme,” Mattar added. “This, in fact, puts in question the integrity, if not the legality, of the whole operation pending further conclusive investigation.”

Bank Audi currently controls about 23 percent of Crossbridge Capital, and Banque Audi Suisse CEO Phillipe Sednaoui has been on the company’s board since early 2016. He declined comment.

Farid Lahoud, the bank’s group corporate secretary, said in an email that “the acquisition of shares in Crossbridge by members of the Bank Audi Group was consistent with, and conducted solely on the basis of, the Group’s own strategic and commercial interests.”

Riad Salame dismissed any suggestion of wrongdoing.

“[W]e vigorously refute having been in a conflict of interest situation or favored any bank we regulate,” he said in an email to OCCRP. “Private matters do not have to be in the public arena in the absence of any irregularities. … I have always drawn a strict line between my private matters and my public position and require that you do the same.”

Crossbridge Capital manages $4.5 billion in assets. Its shareholders include Abdulaziz Ghazi Fahad Al-Nafisi, a Kuwaiti businessman; Nabil Aoun, a prominent Lebanese stockbroker; Julius Baer Investment Limited, a subsidiary of the Swiss private bank; Pierre Fattouch, the late cement tycoon who in 2019 was charged with tax evasion in Lebanon; Ramzi Sanbar, a Lebanese construction magnate; and the owners of Lebanon’s First National Bank, Roland El Hraoui and Rami El Nimer.

But the identity of the firm’s single largest shareholder is a secret.

A company registered in the British offshore jurisdiction of Jersey holds 41.3 percent of Crossbridge Capital’s shares. That company, Dominion Employee Benefit Trustees Limited, is administered by the global private wealth business Dominion. Its beneficial owner is not public record.

One other Crossbridge Capital shareholder, T-Prime Limited, at nearly 1.6 percent, is registered in the British Virgin Islands, with equally secretive owners. Neither BVI, a British Overseas Territory, nor Jersey, a British Crown Dependency, require public disclosure of beneficial owners.

Jersey’s secretive legal arrangements “attract illicit financial flows from across the world," according to the Tax Justice Network. The island in 2019 committed to starting a public register of beneficial owners in line with EU standards, but has been criticized for slow implementation.

Ben Cowdock, Investigations Lead for Transparency International U.K., which campaigns against corruption in the United Kingdom, said lack of transparency in company ownership can facilitate abuse.

“It's no secret that opaque companies are used to hide the identities of their owners, which can help keep conflicts of interest hidden," Cowdock said. “To guard against the abuse of U.K. companies, opaque offshore vehicles holding shares in U.K. firms should be required to declare who truly owns them.”

Jim Henry, a Tax Justice Network Senior Economic Adviser and Senior Fellow at Columbia University’s Center for Sustainable Investment, questioned why a central bank governor would make overseas investments through opaque offshore companies.

“The fact that [Salame] has offshore wealth is not per se illegal," Henry told OCCRP. “The fact that he didn’t report it raises questions about whether it was legal and what the sources of the income are.”