Six years ago, Ecuador inaugurated a new state-of-the-art port in the deep waters off the coast of the once sleepy fishing town of Posorja.

Equipped with security cameras lining the road that leads to the port, biometric controls at the gate, and scanners to check incoming cargo, the $1.2 billion project was designed to keep drugs out.

But trafficking gangs have encroached — quickly and violently.

Data obtained by OCCRP and partners indicates that Posorja has already emerged as one of Ecuador’s leading launchpads for cocaine, highlighting the challenges that South American authorities face in policing ports and protecting surrounding communities.

According to figures provided by Ecuadorian police, the amount of narcotics moving through Posorja has increased dramatically in recent years. In 2024, 15.4 tons of cocaine were intercepted in the district where the port is located — nearly three times more than the year before.

As the flow of drugs has increased, so has the violence; streetside assassinations are now a common occurrence, with homicides having increased 13-fold since the year after the port opened, compared to the five years prior.

“It used to be a place of peace, but now two or three people are killed per week, and shops close earlier,” a local resident who lives near the rural town, and who requested anonymity for safety reasons, told OCCRP.

Police conducting searches in Posorja, Ecuador.

The cocaine produced in neighboring countries and routed through Ecuador — now the world’s leading cocaine exporter — has traditionally been loaded onto shipping containers departing from the city of Guayaquil, which sits some 80 kilometers further inland on the Guayas river and is the country’s most populous urban center.

But Posorja’s prominence is rising, a trend that has been reflected on European shores as well: In Rotterdam, a major gateway for the drug in Europe, Posorja was the number one “loading port” in all of Latin America for cocaine seized in 2024. Authorities in Antwerp also confirmed it had been the top point of origin for cocaine shipped from Ecuador that year, surpassing Guayaquil, while German officials said the number of seizures originating from Posorja had increased, without elaborating.

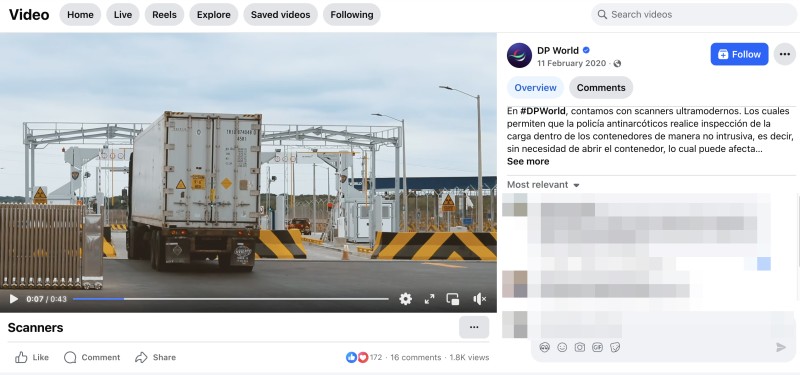

Customs presenting Antwerp port cocaine seizure results and container search methods with scanners and sniffer dogs.

Ruggero Scaturro, a senior analyst at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, said traffickers are likely responding to increased police scrutiny on traditional routes — and that they are drawn to Posorja for the same reasons that legal traders are.

"If a port is competitive and well connected via land infrastructure and also via sea trade to specific important destinations in Europe, then automatically this is going to be attractive to criminal networks," said Scaturro.

When reached for comment, the company that operates the port, DP World Posorja, said it approaches the fight against drug trafficking with “extreme seriousness,” and that its facility is “the safest and most technologically advanced port in Ecuador.”

“Far from representing a vulnerability, the terminal's robust security protocols and active collaboration with law enforcement agencies are designed to safeguard cargo and reduce risks,” a company spokesperson added.

The toll on poverty-stricken Posorja, whose dusty, sun-baked center consists of squat cinder block homes, has been heavy.

“The tranquility of fishermen and residents has disappeared,” a local newspaper recently lamented on its editorial page, calling for the state to intervene in the cartel wars that have left the people of the town “stained with blood.”

The local resident who OCCRP spoke to described a climate of fear, in which no one feels safe from becoming “collateral damage.”

“You don’t know who you're talking to. There are “radars” who transmit information to people from criminal gangs for minimal amounts of money,” the resident said.

A beach in Posorja, Ecuador.

50-year Concession

Posorja once subsisted on its tuna and shrimp fishing industry.

All that changed in 2016, when the government awarded a 50-year concession to DP World Posorja, the local arm of a multinational originally from Dubai, in exchange for constructing a deepwater port along the town’s Pacific coastline. The company partnered with a prominent local firm, Nobis Holding, whose CEO is the aunt of the country’s current president Daniel Noboa, a business scion who was elected in 2023. (Nobis Holding did not respond to requests to comment).

With an estimated budget of $1.2 billion, the project is one of the biggest foreign investments in Ecuador’s history.

By certain measures, it has already been deemed a success: Last year, Posorja became Ecuador’s busiest port in terms of trade volume, plus the new hub for the major shipping company Maersk, which was previously operating out of Guayaquil.

Credit: Google earth pro/Airbus/images from 2016-2024

Credit: Google earth pro/Airbus/images from 2016-2024

But with the growing trade in legal goods, traffickers have found new opportunities to hide their contraband alongside products like bananas, oat flakes, and flowers — or inside the structures of shipping containers themselves. In the first four months of 2025, more than 10 tons of cocaine have already been seized in containers carrying food products.

Across the Atlantic, port authorities in Rotterdam said they seized more than six tons of cocaine from Posorja in 2024, which was nearly double the amount coming from the next most popular loading port, Panama.

Describing this sudden four-fold increase from Posorja as “striking,” an internal report from Rotterdam authorities noted that the Ecuadorian port’s rapid expansion had made it “particularly attractive for criminal abuse, partly because customs capacity is not growing accordingly.”

The trend could also be related to shifts in Ecuador’s criminal landscape following a government crackdown on an “explosive rise in drug-related violence” that kicked off in early 2024, the report said.

Antwerp and Hamburg recorded similar shifts: In the Belgian port, the quantity of cocaine hailing from Posorja tripled between 2021 and 2024, with more than 14.6 tons confiscated over 27 seizures in 2024, while the quantities intercepted from Guayaquil decreased significantly over the same time period, according to data shared with OCCRP. And in the ports of Bremerhaven and Hamburg, German customs authorities confirmed they had seized more cocaine originating from Posorja last year, without providing further details.

A spokesperson for Ecuador’s Undersecretariat of Ports said that increased cargo volume at Posorja in 2024 may have contributed to “greater risks of contamination.”

The seizure data also “demonstrates the strengthening of the work of Ecuador's Anti-Narcotics Police, whose efforts have enabled them to intercept and prevent the international distribution of controlled substances,” they added.

Ecuadorian police, customs authorities, Posorja’s local government, the navy, and Maersk did not answer questions sent by reporters.

‘Final Destination: Antwerp’

Until recently, Ecuador was considered one of Latin America’s safest countries. Then came the cartels, from countries like Colombia, Mexico, and Albania, which have turned the nation into a logistical hub for exporting vast quantities of cocaine to Europe and elsewhere.

Ecuador’s appeal is multifold: Though it is not a producer of cocaine itself, the coastal country is conveniently wedged between top manufacturers Colombia and Peru. It is also the globe’s leading exporter of bananas — the type of perishable good favored by smugglers because of its need to move through ports quickly.

Cocaine found in banana containers smuggled from Ecuador to Europe in 2018.

Over the past five years, Ecuador has emerged as “not probably, [but] definitely the number one gateway of cocaine that is coming from Latin America towards Europe,” Robert Fay, the head of Europol’s Drugs Unit, told OCCRP.

Violence has followed on a national scale, with turf wars driving homicides up some 600 percent between 2018 and 2024.

When the port of Posorja opened for business in 2019, it was the first facility in Ecuador to use scanners designed to identify illegal goods hidden inside shipping containers.

Yet it didn’t take long for traffickers to target the site. Within four months, authorities had already seized more than 230 kilograms of cocaine in containers transporting flowers and bananas to the Netherlands and Poland, respectively.

DP World advertising their scanning system on their Facebook page.

Intercepted chats sent by alleged members of a major drug trafficking network show how quickly gangs jumped on the new location.

"It's from Posorja. Final destination: Antwerp," reads an August 2020 message sent to the alleged boss of the group, who has been charged with leading a drug trafficking organization.

“It's leaving from the yard / Posorja-Hamburg,” reads another text he received that year.

Human Factor

According to Mauricio Santamaría, who led Posorja’s police force until last April, two of Ecuador’s most violent gangs are vying for control of trafficking logistics in the area: Los Choneros and Los Lobos.

These two groups — former allies turned bitter rivals — have been key drivers of the bloodshed that has plagued Ecuador since 2020, leading President Noboa to declare a state of emergency at the start of last year.

In Posorja, the gangs have threatened local residents and used their homes as warehouses to store drugs, said Santamaría.

“They try to force people from their homes to use them for stockpiling, or they extort fishermen," he said.

Police set up a special intelligence unit to prevent the contamination of shipping containers, he told OCCRP.

But they have faced reprisals. Last March, gunmen reportedly opened fire on a local police base, wounding a lieutenant.

While the port has several layers of surveillance measures to control who and what can enter the facility, most of the seizures in 2025 have been made after reaching one of the final barriers of defense: a canine unit that sniffs containers at key intervals in the loading process.

The dogs are able to detect drugs which are concealed in sophisticated ways — such as mixed in liquid form into textiles or other materials — that the scanners cannot always spot.

But the animals have another advantage; they cannot be bribed to turn a blind eye. According to an internal EU 2024 security assessment prepared by a Danish consultancy, Posorja’s personnel were rated as one of the port’s biggest vulnerabilities, with a “high risk” of infiltration and corruption.

The port has put “special measures” in place to address this, the report notes, such as transporting employees out of the facility by bus to prevent traffickers from approaching them. The company also carries out “confidence” assessments on staff every two years, including checking for signs of unexplained wealth.

Yet as Posorja takes on larger volumes of trade, it should anticipate more “pressure on port facility workers to facilitate contamination inside the terminal,” the report noted.

Truck drivers who deliver cargo to Posorja have also reported facing pressure. In testimony from a 2023 court case, a driver whose Rotterdam-bound banana shipment was later found to contain 1.1 tons of cocaine described how men entered his vehicle at gunpoint on the way to the port.

“They instructed me to enter [the port] and not say anything to anyone, warning that they knew where I lived and with whom, and that if I said anything, they would kill my family and me,” said the driver, who is seeking to appeal his drug trafficking conviction.

The drugs were later discovered by the canine unit.

A Chilling Effect

The surge in violence, which often takes place in public places, has had a chilling effect in Posorja.

In the five years before the port opened, there had been just 13 murders in the town. Since 2020, there have been more than 200. Police suspect the majority of the killings are related to the drug trade.

Families and friends mourn the victims of a massacre in a bar in Ecuador's Guayas province, linked to drug trafficking, on July 29, 2025.

Scaturro, the security analyst, noted that it’s especially difficult to escape the reach of traffickers in a small town like Posorja — home to some 33,000 people — whose economy is now centered around the port.

“I would assume that at least half of the people that live in the village are in a way or another involved in the port businesses, from dog [handlers] to the truck driver to the guy at the gas station,” he said.

This leaves them “exposed” to the “illicit activity [that] takes place and manifests in those premises.”

On July 12, a video showing a man’s body lying facedown on a rural road was posted by a Facebook page that covers local news.

“Violence and death continue unabated in Posorja,” the post reads. It was the 25th killing of the year.

Paul Vugts (Het Parool) and Brecht Castel (Knack) contributed reporting.