Reported by

Emerging from an anteroom wearing a British-style red army jacket, a blue sash, and a crown of cowrie shells, the slightly-built king shuffled stiffly into his office, his eyes bloodshot and a scar running across his jaw.

His Majesty David Peii II took a seat behind a desk cluttered with bank notes bearing his portrait and a well-worn laptop that he uses to warn the world of a coming global financial collapse — and the spectacular shower of riches to come.

Once a pious young man known as Noah Musingku, His Majesty became famous for running a Ponzi scheme that is estimated to have stolen tens of millions of dollars from victims across the South Pacific around the turn of the millennium.

Fugitive Ponzi schemer Noah Musingku who proclaimed himself the king of Bougainville under the regnal name David Peii II.

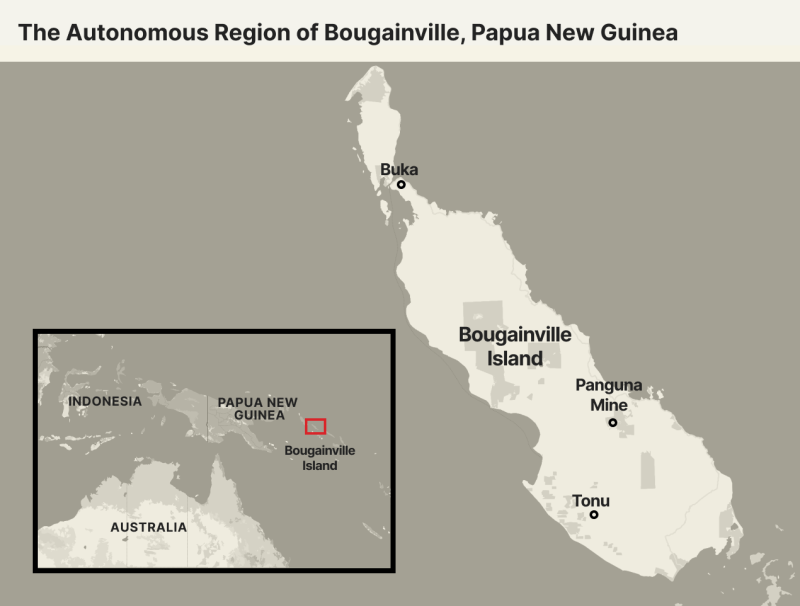

Living for two decades as a fugitive deep in the interior of Bougainville, a lush and war-scarred autonomous island on the far eastern edge of Papua New Guinea (PNG), Musingku has reinvented himself as the divinely anointed ruler of a small fiefdom of locals who believe he will make them all billionaires any day now.

But OCCRP traveled to Musingku’s metal-roofed royal compound to follow a different, unreported story.

For years, tales have trickled out about curious foreigners, usually Western men, journeying to the territory that Musingku named the Twin Kingdoms of Papaala and Me’ekamui to make their fortunes.

Unlike the miners who typically arrive to exploit this gold- and copper-rich island, these foreigners seek a different form of treasure: the crudely-printed currency on Musingku’s desk, known as the Bougainville Kina, or BVK.

The money is illegal in the eyes of PNG authorities, and worthless in the global financial system. But for Musingku’s adherents, these strips of glossy paper are more real than the U.S. dollar and a better investment than even the buzziest tech stock.

Noah Musingku, wearing a white glove, lays a hand atop bundles of his own banknotes.

Speaking to OCCRP, Musingku breezily denied accusations that he is a con artist or that the colorful bills in front of him are fake.

“The first lot was printed in Canada. The next one was in Russia,” the king rasped, gesturing across his desk. “And this one’s printed in Australia.”

“It’s hard to stop them,” Musingku said of the followers who have forded rivers and braved the cratered roads to reach his compound. “They keep on coming, keep on coming.”

Who are these visitors? A red guestbook by the door offers some clues.

Stretching back as far as 2008, it catalogues a stream of adventurers — a builder from Sussex, England; a pair of evangelical megachurch pastors from Florida; a Japanese businessman called to visit the king by the spirit of Admiral Yamamoto.

These are just a fraction of the thousands of people around the world who have become enthralled by the king — and his self-styled BVK currency — without ever meeting him.

Millions of dollars have been lost, lives have been upended, and a handful of people have faced serious prison time.

This is the story of how a fugitive in one of the most isolated outposts of the Pacific united a global empire of fringe beliefs, where everything — from the nature of money, government, and the very fabric of reality itself — is up for debate.

‘An Abomination in God’s Eyes’

One of those drawn to Musingku’s world was an American father of 10 named David Johnson.

For the close-knit and god-fearing people who knew him on the plains of North Central Iowa, Johnson seemed like a man you could trust.

A devout Christian, he had grown up in the area before following in his father’s footsteps to become a financial adviser.

But the trauma of the 2008 financial crisis shattered his faith in the safety and legitimacy of the U.S. financial system.

The U.S. dollar, he concluded, was worthless — just a “fiat currency” backed by nothing but debt and government lies. The economy was a house of cards, and a reckoning was coming.

Fortunately, he saw a way out.

He had learned that on the other side of the world, a righteous Christian king, Musingku, was peddling a currency supported by something real: billions of dollars in untapped gold beneath Bougainville’s surface.

David Johnson.

“I know this fiat, debt-based monetary system is evil and wicked and satanic and an abomination in God's eyes,” he told OCCRP. “So when I found [the BVK], I'm like, ‘Wow, this is so awesome.’”

What Johnson had stumbled across was an exotic variation of a growing trend across much of the world: money-making schemes undergirded by beliefs in arcane, anti-government conspiracy theories, typically with their roots in right-wing and libertarian thought.

This is a corner of the investment world often tied up with the ideology of so-called “sovereign citizens,” who use complex and confusing pseudolegal arguments to claim they are not subject to government authority, and are exempt from everything from paying taxes to carrying a driver’s license.

Modern “fiat” currencies like the U.S. dollar, which was decoupled from the value of gold in the 1970s, come in for particular ire, as they are seen as simply backed by the formal word of a government sovereign citizens see as fundamentally illegitimate.

Having rejected the authority of everything from the Federal Reserve to the British Crown, “sovereigns” seek incredible returns in obscure investments based on novel sources of legitimacy, like Iraqi dinars or century-old bonds issued by China’s pre-revolutionary government.

They have also flocked to the BVK.

That’s what happened to Johnson. When he heard about Musingku’s currency, he decided it was just too good an investment to keep to himself. Around 2012 he began pitching family friends and church acquaintances on the BVK.

Investors could get a piece of the action, Johnson told them, by opening up a BVK-denominated account via a website for the king’s own sovereign financial institution, the International Bank of Me’ekamui (IBOM), which was offering compound interest rates as high as 100 percent a month.

Lois Roose contributed $5,000 of her retirement funds, hoping to use the returns to support her foundation for the homeless and her church.

Carly Schaefer invested $150,000 from her late mother’s estate believing it was a secure foreign investment opportunity.

“You're a Christian. I trust you,” Schaefer recalled telling Johnson, according to records from his 2017 criminal trial on a series of theft charges, in which he was later convicted.

Johnson told his clients that another economic meltdown was coming. Investing in the BVK scheme would protect them.

“So it was like, you know, let's take some of this [money] and put it in a sock and bury it for a while,” he told the court in Iowa’s Carroll County.

”And then we'll come back out… after the sun is shining again and the storm is gone.”

'I Saw the Growth of my Money, the Profit, I was Really Excited'

Resembling a spatter of deep emerald on a map of the South Pacific, Bougainville is a land of forests and volcanoes cursed by war and natural wealth.

Although the island is technically part of PNG, its 300,000 inhabitants are ethnically and culturally closer to the neighboring Solomon Islands.

In 1568, Spanish explorer Álvaro de Mendaña named the archipelago after the biblical King Solomon, believing he had discovered the source of the king's legendary gold.

He wasn’t so far wide of the mark.

As an Australian colony, Bougainville became a central node in global commerce in the 1970s when the multinational Rio Tinto opened up Panguna, at the time one of the world’s largest gold and copper mines.

Despite the billions of dollars it generated, the mine provided little wealth for locals, while trashing the forest and rivers.

In 1988, fed up Bougainvilleans went into revolt.

Armed with old guns and Samurai swords left by Japanese soldiers defeated on the island in World War II — as well as a handful of mine vehicles converted into makeshift tanks — local independence fighters managed to quickly oust the mining company and the forces of a newly independent PNG.

In response, PNG put Bougainville under a naval blockade that sealed it off from the outside world. Imported goods, from medicine to canned food, disappeared from shelves.

Without imported fuel, locals built hydropower dams and modified cars to run on coconut oil. Money, an abstraction at the best of times, ceased to have meaning.

Public health experts estimate 15,000-20,000 people died during what locals call the Crisis, many from preventable diseases.

A view of Bougainville.

But while Bougainville’s modern economy evaporated, a young and pious man originally from Bougainville was getting fabulously rich nearly 1,000 kilometers away in the PNG capital, Port Moresby.

Noah Musingku and his brother founded an investment vehicle in the late 1990s, U-Vistract, that promised to double investor funds every month.

U-Vistract had all the hallmarks of a classic Ponzi scheme. Named after Charles Ponzi, who defrauded thousands of investors in Boston in the 1920s, Ponzi schemes promise artificially high rates of return to early investors — but they are actually being paid off with funds from later investors.

Such schemes inevitably collapse when too many investors demand redemption, or when the scheme fails to attract a sufficient number of new investments.

Noah Musingku’s U-Vistract is built on Pentecostal Christian belief mixed with traditional Bougainville myths.

With Musingku flaunting his wealth across Port Moresby, and stories swirling of the prominent Papua New Guineans who had made money off the scheme, U-Vistract spread like wildfire throughout the South Pacific and parts of Australia.

In PNG, it is estimated that as much as seven percent of national gross domestic product was soaked up at the time into U-Vistract and other “fast money” schemes.

In Bougainville, the scheme’s explosion coincided with the end of the Crisis and the emergence of a tentative peace.

Naomi Sania, a market vendor in Bougainville’s capital, Buka, was one of legions of locals who joined lines to sign up.

She was amazed when the approximately $90 she invested had doubled within two weeks. Although she was able to take some of her money out, the temptation of continued gains was just too much.

“When I saw the growth of my money, the profit, I was really excited. So I just rolled on,” Sania said.

She watched as her balance grew on paper to about $12,500.

But then the payouts stopped. Like tens of thousands of others across Bougainville and the wider region, Sania would never see her money again.

Regulators shut down U-Vistract’s Australian operations in 1999 after finding it had deceptively taken about $600,000 from local investors. PNG’s government followed suit, revoking U-Vistract’s license to operate.

Musingku and his scheme were declared insolvent by a PNG court the following year. A court-appointed liquidator concluded at least $20 million to $30 million had moved through bank accounts related to the scheme before it collapsed.

King of The No Go Zone

Musingku was undeterred. Charged by PNG authorities with contempt of court for continuing to promote his scheme, he first fled abroad to the Solomon Islands, but was swiftly kicked out. Around 2003, he returned to Bougainville.

By then the island was mostly at peace and was formally run by an autonomous government of ex-rebel leaders. But near the abandoned chasm of the Panguna mine, a disaffected senior ex-rebel, Francis Ona, had staked his own claim to rule.

The Panguna mine has become a destination for artisanal miners seeking gold since its closure.

Musingku traveled to Ona’s breakaway region, known as the No Go Zone, and made him an intriguing offer: Ona would declare himself ruler of a supposedly ancient kingdom, Me’ekamui, that would be the official government of a fully independent Bougainville, and Musingku’s U-Vistract concept would become the basis for its financial system. Ona accepted.

When Ona died in 2005, Musingku gathered his followers and parts of Ona’s armed faction and moved to his ancestral village of Tonu, deeper in the No Go Zone.

In this new capital, he crowned himself king. But by then he was essentially broke, according to John Cox, an Australian social anthropologist who has studied Ponzi schemes in the Pacific.

Musingku ratcheted up his rhetoric in response. U-Vistract evolved from a mere get-rich-quick scheme into the promise of a holy revolution that would bring wealth and freedom to Bougainville.

Musingku began stringing along his still-unpaid followers with a story that he was “a massive reformer of the whole global financial system,” Cox said.

The pitch was that “as God's plan is going to be revealed, and people are signing on to this all over the world… all the wealth that you see white people enjoying in the New York Stock Exchange or London or wherever — we're going to have that.”

That sort of escalation is “classic in the psychology of cognitive dissonance,” Cox explained.

“Dial up the rhetoric, increase their outreach, really dig in rather than thinking ‘gee, this whole thing’s falling apart.’”

Musingku’s village of Tonu soon developed all the trappings of a pseudo-state, with its own royal palace and parliament made from wood, thatch, and corrugated metal roofing.

Noah Musingku’s royal palace in Tonu.

At its heart was also a clutch of buildings that he claimed were financial institutions — a central bank, a local bank, and a bank for international customers, the International Bank of Me’ekamui, or IBOM — that dealt in the BVK.

The threat this posed to Bougainvillean authorities was obvious. In 2006, a group of fighters aligned with the island’s legal government attempted to storm Tonu.

They killed four of Musingku’s bodyguards and wounded the king with a gunshot through his neck, but the raid was ultimately unsuccessful.

From Con Artist to ‘Cult’ Leader

Since then an uneasy peace has prevailed. Still officially a wanted man today, Musingku does not leave his royal territory, a loosely defined region with several thousand followers in the island’s south.

In 2019, over 98 percent of Bougainvilleans voted for full independence from PNG, which is due as soon as 2027. At this key moment, the government appears to have decided that picking a fight with an armed and aging conman is not in its interests, and has not pursued Musingku.

Left to his own devices for two decades, Musingku’s world has evolved into something often called a “cargo cult,” a controversial term coined to describe millenarian cultural movements that emerged in Melanesian islands in response to colonization and World War II.

Believers would mimic the rituals of a more technologically advanced society in the hope it would bring them actual cargo like food, goods, and technology.

Such movements have seen locals attempt to summon foreign riches by, for example, building fighter planes from wood, or radios from coconuts.

In some ways, Musingku’s mimicry of international finance fits the definition of a cargo cult, Cox said.

But the term is fraught with colonial baggage, he said. And after all, aren’t the West’s faith-based financial trends — from sovereign citizen schemes to cryptocurrency — their own form of cargo cults?

“There are all these ways of creating dark money that having an alternative form of sovereignty – at least in your head – facilitates,” Cox said.

Indeed, Musingku was adept at straddling these two worlds.

From the earliest days of his return to Bougainville, Musingku has forged ties with Westerners drawn to his vision.

One of the first was Jeffrey Richards, a self-styled royal who prefers to be called Prince Jeff. In the 1980s, he helped form a microstate in rural northern Australia called the Independent Sovereign Neutral Nation of Mogilno, based on early sovereign-citizen-style ideas.

He told OCCRP he was invited by Musingku to Bougainville in 2004 to help set up his new kingdom.

“He had the belief of sovereignty, but he didn't know exactly how to go about it,” Prince Jeff told OCCRP.

“So I told [Musingku], you know, he needs to create his flag, create his postal stamps and then … [proclaim] sovereignty.”

Prince Jeff convinced two men — one of whom owned a Cessna private jet — to fly clandestinely to the airstrip near the abandoned Panguna mine.

The pilot was detained but Prince Jeff and the remaining passenger, his acquaintance “Lord” James Nesbitt, disappeared into the No Go Zone.

After two “mind-boggling” years in Bougainville’s interior, which included witnessing Musingku’s elaborate coronation, the pair were arrested for immigration violations in 2006 during a trip to the island’s capital Buka and swiftly deported.

One of Prince Jeff’s principal legacies was a piece of infrastructure that would allow Musingku to spread his financial gospel far and wide: a satellite internet connection.

In 2008, on the eve of the global financial crisis, Musingku used his new internet connection to launch IBOM’s website.

IBOM’s website

‘Like Tokens for Rides at a Carnival’

The man who truly set IBOM off as a global phenomenon was a retired electrical engineer from Texas, Benjamin Young.

IBOM appeared to be a perfect fit for an operation that Young co-headed, the Internet Catalogue Club (ICC), a network of websites that evoked both old-school coupon clipping and fringe anti-government ideology.

“Frankly, the entire global banking system is built on fraud,” Young told OCCRP in an interview.

Charging a $25 entry fee, the ICC allowed members to trade with each other using digital tokens, including ZCash, a pseudocurrency found by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 2011 to have taken $4 million from investors without giving them the promised returns. (Young denied any wrongdoing, but was eventually barred by the SEC from associating with a securities broker or dealer. He and a co-defendant argued in court that ZCash was never meant as an investment and was intended for use inside ICC’s closed system, “like tokens for rides at a carnival.”)

Young’s ICC also offered members the opportunity to invest in obscure financial instruments that sovereign citizens often claim can be exchanged as legal tender, such as promissory notes, which are essentially legal IOUs, and international bills of exchange (IBOEs), a kind of legal document used in international trade.

The ICC was a place where members could easily sink their U.S. dollars. Getting them back out again was more difficult.

The club reminded its members that it adhered “to the Biblical injunction against litigation.” If they were unhappy with a product or service they had bought, the ICC offered them reimbursement – in the form of another of its in-house tokens.

In the BVK, Young found a new form of currency he could offer members. Around 2011, the ICC and Musingku reached an agreement that would allow club members holding promissory notes, IBOEs, and Iraqi dinars to convert them into high-interest BVK accounts — after they paid an additional $450 in U.S. fiat currency.

Musingku received a torrent of “money” in the form of sovereign citizen IOUs, as well as what looked like international recognition for his self-styled financial system. ICC members, meanwhile, got the promise of exponential returns.

“[Musingku] provided at that time a 75-percent-per-month compounded interest,” Young told OCCRP.

Such a rate would convert a minimum deposit-holder into a millionaire in just over a year.

The ICC members who ended up opening accounts at IBOM, Young said, were “all very happy.”

Meanwhile, Young entered himself into the U.S. government’s foreign agents register as an official diplomat of Musingku’s royal government.

ICC members took over the running of the IBOM website, and fanned out around the world to promote the scheme, at investment seminars and online, armed with sovereign citizen-style talking points and allusions to the Biblical myth of King Solomon’s gold.

Patrick Steensma, a Dutch lawyer and alternative medicine practitioner who has written a book about the “International Banking Cabal” that manipulates world events, was drawn in by the ICC’s glittering pitch.

In 2011, he traveled to Musingku’s kingdom to help cement the alliance between Musingku and his new foreign partners. He spent almost three weeks with the self-styled king, and fell in love with the island and its long-exploited people.

Steensma accepted an appointment as Musingku’s royal adviser.

“He trusted me, I think, and he needed somebody like that,” he said.

It would be the first of five trips to Bougainville.

The BVK Goes Global

With the ICC’s endorsement, word of the BVK investment spread across the world. At least 1,500 people from North America, Europe, and Australia opened IBOM accounts. Among them was Johnson, the God-fearing financial adviser from Iowa.

Originally encouraged by a friend in Texas to convert his Iraqi dinars into BVK, he then invested U.S. dollars via the ICC, and sought out new investors to open high-interest accounts at Musingku’s bank.

The half dozen people who gave Johnson over $330,000 for their BVK accounts never saw their money again.

The man who eventually put Johnson in prison was Rob Sand, a boyish-looking 43-year-old who is currently the narrow favorite to become the next governor of Iowa in 2026.

As an assistant state attorney general in 2017, Sand successfully prosecuted the case against Johnson in the Carroll County court.

He saw Johnson as a man on the verge of bankruptcy who used his Christianity as a front to deceive those around him — but said he was still struck by how committed he was to the fantasy of the king’s money.

Noah Musingku has printed banknotes bearing his own face, which are used as the official currency in his self-proclaimed kingdom.

Throughout his investigation, trial, and eventual conviction, Johnson expressed regret that people felt that they had been ripped off, but denied he had done anything wrong.

Before going to court, Johnson spent much of his interrogation trying to convince the detective interviewing him that the BVK was actually an excellent investment, Sand said.

And even as he stood before the judge for his sentencing, Johnson insisted he would be able to redeem the currency via the ICC’s tokens and repay his victims.

Although prosecutors hadn't asked for it, the judge slapped Johnson with the maximum possible sentence of 20 years in prison.

"How do I protect society from someone who doesn't think they've done anything wrong? How do I do that? I have to put them in prison," Judge Kurt Stoebe said.

Johnson was one of at least two American investment advisors to receive prison time for BVK-related schemes.

The following year, Edward Campell, an Ohio man who the U.S. justice department said falsely claimed to investors to be a former Navy SEAL, was sentenced to five years for taking over $1.4 million from at least 44 people. He did not respond to questions from OCCRP.

Summarily ‘Extinguished’

It was Musingku himself who brought it all to a halt.

While the Internet Catalogue Club was getting cash from depositors, according to court records from an Australian civil fraud trial, Musingku and some of his supporters say he did not see any of it.

By 2015, Musingku had started to believe the deposits being passed on to him by the ICC — in the form of IBOEs and promissory notes — were entirely worthless. The man behind the Pacific’s most notorious Ponzi scheme decided that he himself was being scammed.

In a series of royal decrees, Musingku denounced the investment products provided to him by the ICC as “a Deceit and Fraud and were presented to me and officers of IBOM under Fraudulent Misrepresentations and Breaches of Good Faith.”

Musingku froze IBOM’s operations. The accounts set up in partnership with the ICC – and the trillions of BVK supposedly held therein – were summarily “extinguished.”

Western BVK promoters scrambled to mollify those who lost out by offering them the ability to again transform their holdings into other exotic investments, including the ICC’s in-house currency.

ICC co-founder Young offers a different account of what transpired. He told OCCRP that in 2015 he received information from the U.S. Embassy in Papua New Guinea that Musingku’s currency was illegitimate, and ended the ICC’s relationship with Musingku.

Because IBOM investors were able to convert their BVK losses back into ICC tokens, there was “no harm done,” he said.

“If I had even dropped a piece of paper on the sidewalk, I’d be in jail now. They’re all coming after me because everything I’ve done is completely legitimate,” he said.

Young did not respond to follow-up questions sent by OCCRP.

A worker at one of Musingku’s self-declared banks stamps account-opening documents.

‘Semi La-La Land’

“That’s a 100% lie,” said Steensma, the Dutch alternative healer turned royal adviser, said of Young’s account.

Although Steensma had come to Musingku via the ICC, he had come to believe its financial instruments were bunk.

In 2015, he secretly traveled back to Bougainville to break the news to Musingku and help him draft his royal decree zeroing out ICC members’ accounts.

Asked by OCCRP if he regretted promoting something that he later concluded was a scam, Steensma said that he, too, had been hoodwinked.

“[Young and his associates] have a very good way of disguising things and smoke-screening things, and then at some point it becomes apparent.”

After the bond with his global following was sundered, Musingku spent a long spell in relative obscurity.

Steensma said he stuck with the king for a while, and even helped him launch a new IBOM website. But by 2017 his belief in Musingku was also beginning to ebb.

“Many scammers flocked to [Musingku] of course. And yeah, he didn't have the wherewithal, the skill set to discern a good guy from a scammer,” Steensma said.

Having defrauded thousands of people with his U-Vistract Ponzi scheme in the 1990s, Musingku may have begun to suffer from overconfidence, leaving him blind to manipulation.

Or, in Steensma’s version of events, Musingku was just too naive.

“He's not of bad faith, he just has a bit of a semi-la-la land idea of how we can set up [his financial system],” Steensma said.

‘Everyone is Tired of the Beast System.’

A decade after the collapse of IBOM’s website, many of Musingku’s followers remain undaunted.

Traveling through the wretched moonscape of the abandoned Panguna mine to Musingku’s kingdom in mid-2024, an OCCRP reporter found Musingku’s financial dreams very much alive.

Amid the oppressive tropical heat, the well-manicured lawns of the royal compound were populated by a small smattering of faithful, most of them old men from around PNG.

Musingku was a near-immortal being, they said.

“He’s already signing decrees for 1,000 years,” Philip Mapah, his minister of finance, told OCCRP. “He will live beyond 1,000 years.”

Musingku’s minister of finance, Philip Mapah, stands at a teller’s desk in one of the king’s self-declared banks at his royal compound in Tonu, Bougainville.

The king had been making moves.

In 2023, he launched a foreign exchange app that claimed to be able to convert BVK to 40 different currencies. (It has since closed down, and the Indian software developers who made it say they were never fully paid.)

But the best was yet to come, Musingku told OCCRP in the gloom of his office, surrounded by the stacks of BVK, a globe, and souvenirs from foreign visitors.

The repeated failures of his financial structures to gain international recognition were all part of the plan.

Like Jesus Christ himself, Musingku said his system needed to be killed before it could be resurrected.

But unlike the Son of God, he needed more than just three days.

“It’s a big system. I cannot do it in three weeks, I cannot do it in three months, I cannot do it in three years. It has to be three decades,” Musingku said.

Soon, Musingku said, he would declare a state of emergency that would kick off his so-called Universal Payout Program (UPP), the long-awaited financial rapture that would finally make his followers unspeakably rich.

“Now, [the global financial] system is going to be destroyed and taken over.”

'I’m In For a Couple of Trillion'

In Musingku’s third act, he is once again looking to entice international investors — including those who had already been burned in the online banking saga.

Some foreign investors who had their BVK accounts wiped out before have been offered the ability to start earning some of it back, via a scheme involving a $20 down payment and another alternative currency that is mostly used in Zimbabwe.

In April, Musingku finally announced he was beginning his universal payouts.

Initially promised in just weeks or days, the payments have, perhaps unsurprisingly, faced delays.

Musingku is now sending near-weekly emails to his global followers recounting the various court cases, paperwork, and medical misadventures that keep getting in the way, but which will soon be overcome.

“Everyone is tired of the Beast system. They’re tired of the Serpentine system,” he wrote in one September email that promised electronic payments “from the coming week onwards.”

Noah Musingku is in his red uniform and crown, which reads “KING.”

When that deadline failed to arrive, Musingku sent out another email boasting of “letters of support” he had received from the United States and the United Nations.

Five days later, he just needed to hop on a quick conference call with the president of an unnamed country. It was, he wrote, “only a formality before releasing our funds.”

Ten days later, still no payouts. Nothing to fear.

“The whole world is dancing to our universal payout music knowingly or unknowingly.”

Among those eagerly waiting is Prince Jeff, the Australian sovereign citizen.

Come payday, Prince Jeff will help build roads and houses in Musingku’s kingdom, he said.

“I should be able to help him now do his projects once I get paid, because I'm in for a couple of trillion [dollars],” Prince Jeff told OCCRP.

Also ready to receive his windfall is Johnson, the financial planner and father of 10 from Iowa.

Although Johnson had originally been hit with a 20-year sentence back in 2017, he was released on parole in just under two years.

Johnson’s stint in prison did nothing to dissuade him from the belief that the BVK is a solid investment backed by God and gold.

“As soon as the king releases his funds and all the I’s are dotted and the T’s are crossed, we are expecting to have some funds here.”

“I’m saying in the next couple of weeks.”