Reported by

When Swedish health authorities investigated more than a dozen cases related to one doctor, they found he had inappropriately administered medication to multiple patients, causing one of them to suffer a double lung collapse.

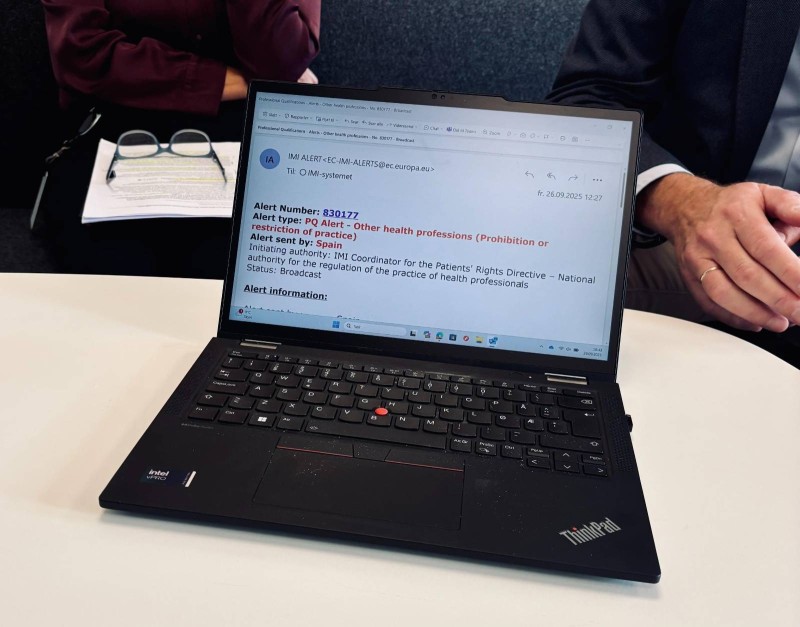

Citing inadequate medical knowledge and patient safety risk, authorities revoked the doctor’s license in 2021, and immediately filed an alert to the Internal Market Information System (IMI).

That alert went out to the other 29 countries that make up the European single market. Norway followed suit, revoking the doctor’s license there and sending a second alert a few months later.

By then, the doctor was practicing in Cyprus. But authorities in that country didn’t read the warnings — a common issue, according to data obtained by reporters, which shows that only about one third of the jurisdictions open the alerts.

In Cyprus’ case, authorities didn’t access the alerts until this past October — the day after OCCRP and media partners published Bad Practice, which exposed how doctors are able to hop jurisdictions and keep working despite losing their licenses for serious offenses.

Now, journalists have obtained IMI alert records that contain access logs, confirming which authorities opened the warnings.

An analysis of more than 500 alerts issued about doctors in 2024 and 2025 reveals a troubling pattern: While only a third of jurisdictions open the warnings, even fewer take the extra step to access personal data, which includes the identity of the disciplined doctor.

Even worse, half of the states that are part of the IMI didn’t open any of the alerts filed for “substantial reasons” last year — including Cyprus.

The Bad Practice investigation also found that some countries rarely or never file alerts about the disciplinary actions, which they’re obliged to do under EU rules.

Under EU regulations, member states are not required to consult the IMI alerts. But the data analysis showing that many health authorities don't look into the warnings raises questions about the effectiveness of the system. The findings also bring up serious concerns about patient safety.

“It is clear that the countries that have not yet used the available functionality in IMI need to change both their attitudes and actions in order to contribute to increased patient safety in Europe,” said Sjur Lehmann, director of the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision.

“In addition, the IMI system itself should be improved, making it easier to use,” he told OCCRP’s Norwegian media partner, VG, in an email.

‘Inefficient’ System

Lehmann's suggestion that the system needs improvement appears to be shared by others who find it cumbersome to use.

The national IMI coordinator for Cyprus told OCCRP’s Cypriot member center, CIReN, that the emailed alerts are redacted due to data protection. Therefore, a recipient must take further steps to establish the full content and relevance of the alert.

Cyprus is not alone in describing the process as burdensome. Other authorities have admitted to not reading the alerts for similar reasons.

Belgian authorities told OCCRP’s media partner De Tijd that they don’t proactively open warnings about healthcare providers. They added that the emailed alerts don’t contain the name of the medic, and that the system is not synchronized with national databases to help identify relevant alerts about doctors working in their country.

“The only way to process all those alerts would therefore be through manual control, case by case, which is labor-intensive, inefficient and difficult to achieve,” said Federal Public Service Public Health spokesperson Annelies Wynant.

Eglė Savulienė, who heads Lithuania’s healthcare accreditation authority, shared the same complaints with OCCRP’s media partner 15min earlier this year.

She said it was “not possible to identify which [doctor] is being referred to from the received electronic notification.” She added that ”in order to review the information, I have to go to the identification number indicated in each letter. We simply do not have enough human resources to review everything every day.”

The IMI system costs about 2 million euros per year ($2.4 million) to run, and is used for alerts regarding multiple regulated professions, not only doctors. The EU Commission said in an emailed response to questions that it is “continuously working on improvements, for example by adding new functionalities, making the system easy to use.”

“The functioning of IMI Alert system in the broad sense is based on cooperation between Member States and their compliance with the obligation to send alerts and on the adequacy and quality of legal and operational national frameworks concerning authorisation of medical personnel,” the commission said.

‘Challenges Patient Safety’

The records obtained by reporters show that 15 countries did not access any IMI alerts about medical professionals issued last year, which were filed for “substantial reasons.” They are: Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, France, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovakia, and Slovenia.

Substantial reasons for filing an alert may include misconduct, ongoing disciplinary measures, or criminal convictions, according to the European Commission.

Another three countries — Austria, Estonia, Finland — opened fewer than five alerts.

Several countries do consistently read alerts, according to the data. Authorities from Sweden, Spain, Norway, Netherlands, Malta, Poland, Ireland, Italy, and Denmark appear to have accessed all — or almost all — the “substantial reason” alerts sent last year.

But even though Norwegian authorities use the system diligently, Minister of Health and Care Services Jan Christian Vestre said it needs improvement.

“It is not satisfactory, and it challenges patient safety throughout Europe,” he said in an emailed response to questions.

Norway has deployed a bot to read all the alerts sent by the IMI system, which is reflected in the 100 percent access rate in 2024. But even that innovation has not led to a bulletproof review process.

In the Bad Practice investigation, VG identified multiple doctors who were licensed in Norway despite being banned in other countries for serious offenses, including sexual assault. Norwegian authorities have since launched dozens of investigations, and suspended or revoked the licenses of at least seven physicians.

Cross-border communication is key to ensure that authorities in different jurisdictions are able to identify banned doctors and investigate them, according to Vestre.

“When we have a common labor market for healthcare personnel, it is important that information exchange across countries is practiced in a good way,” Vestre said. “I still believe that the way IMI is organized and functions today is not sufficient.”