Nadia, a resident of the impoverished Venezuelan fishing town of Güiria, does not know if her husband is alive or dead.

He disappeared in early September, when the United States launched the first of more than 20 military strikes on alleged drug boats plying the seas off the coast of her Caribbean home, as well as further afield in the eastern Pacific.

While President Donald Trump’s administration has defended this deadly barrage as a lawful conflict with “narco-terrorists,” critics have denounced the attacks as extrajudicial killings.

The strike that appears to have taken Nadia’s husband on September 2 has generated particularly strong condemnation after it emerged the U.S. military bombarded the vessel with a second missile to kill survivors who were seen clinging to the wreckage. Numerous experts have said this violates international law.

The USS Sampson (DDG-102), a U.S. Navy guided-missile destroyer, docks at the Amador International Cruise Terminal in Panama City, Panama, on September 2, 2025.

While the maelstrom of controversy swirls in Washington, Nadia and other kin of the deceased in Venezuela remain in the dark about the fate of their loved ones, whose identities have yet to be officially confirmed.

“I haven't held a mass, nor a prayer,” said Nadia, whose name has been changed to protect her identity. “No authority gives me an answer.”

Whether her husband was killed in the first or second strike does not change the circumstances of her grief, she added. When asked about his line of work, she said: “I never asked him what he was doing, and he told me he was a fisherman.”

Nadia and other residents of the picturesque but poverty-stricken towns along Venezuela’s coastline have long lived under the thumb of local criminal groups who use its sandy shores as a launchpad for ferrying cocaine to the U.S and Europe.

Now, the people of Güiria and other fishing enclaves find themselves squeezed between two other threats: the specter of U.S. missiles, which have claimed more than 90 lives at sea, and what locals describe as a clampdown by security forces from the autocratic regime of Nicolás Maduro.

The port of Güiria in Valdez Municipality, Venezuela.

Residents in towns along the states of Falcón and Sucre, whose peninsulas jut out into the Caribbean sea, told OCCRP that Venezuelan authorities have descended on their long-neglected communities, where many people live in ramshackle homes and often go without basic amenities such as electricity and clean drinking water.

A map of Venezuela's coastline, highlighting Sucre and Falcón states.

Since the attacks, security officers have carried out patrols of the region, made heavy-handed arrests, and searched the homes of the deceased, locals told OCCRP, speaking on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals. They described a climate of intimidation that has left many afraid to speak about the incidents, or post about them on social media.

“People are afraid when they see these officials,” a community leader in Güiria told OCCRP. “For fear of going to prison, being disappeared, tortured … people know what happens to those who are detained.”

While the Trump administration has been accused of overstating the threat posed by these alleged drug-running boats, critics of Maduro say his government has downplayed the reach of traffickers in these communities and Venezuela at large, and is desperate to control the narrative.

“The regime has tried to impose silence in the entire country, in the coasts, neighborhoods, with its control of the media, censorship of criticism, [and] persecution of dissent,” said Carlos Tablante, a former Venezuelan politician who led the country’s anti-drug commission in the 1990s.

The Venezuelan government, which waited almost three months to announce an investigation into the strikes and its victims, has sought to project an image of calm that is at odds with the fear and insecurity described by locals who spoke to OCCRP. In a recent comment to the press, Venezuela’s vice president assured that the nation’s fishermen “do not fear any military might and continue fishing and casting their nets in the Caribbean sea, exercising their political and economic sovereignty."

Lying close to a porous border with Colombia, the world’s top cocaine producer, and offering broad access to the sea, Venezuela’s 2,800-kilometer Caribbean coastline has for decades served as a departure point for boats and airplanes loaded with the narcotic. According to the U.S. and groups like Transparency International, this lucrative trade has flourished thanks to support from a military and government riven by corruption.

A clandestine coca processing laboratory in Colombia, within the Amazon forest.

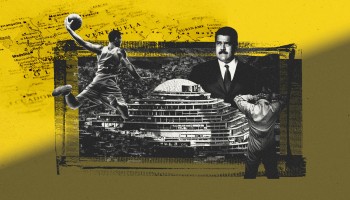

Maduro himself was indicted in a New York court in 2020 alongside other senior officials on charges including “narco-terrorism conspiracy,” for allegedly working with Colombian guerillas to “enrich” themselves and “flood” the U.S. with cocaine. While the Venezuelan leader has denied the allegations, two high-ranking generals tried in the U.S. have pleaded guilty to that and other charges.

Venezuela’s Defense Ministry and spokespersons for the Communication Ministry and National Assembly did not answer queries sent by reporters in time for publication. The Interior Ministry and the Office of the President could not be reached for comment.

When asked about the strikes and their legality, White House spokesperson Anna Kelly told OCCRP they had been launched against “designated narcoterrorists bringing deadly poison to our shores."

‘Strange boats passing’

Known for its colorful carnival festivities and colonial-style architecture, Güiria was once kept afloat by a fishing industry that saw boats go out trawling for shrimp and fish, a practice which was banned for environmental reasons in 2009.

Not long after, the fishermen who remained were battered by Venezuela's crippling economic crisis, which sparked fuel shortages and soaring prices that have left vast swathes of the population facing severe food insecurity.

Today, the state continues to cap the sale of subsidized gasoline at quantities that fishermen said fall short of what they need in order to travel the distance to turn a profit.

“There used to be 10 fishermen on this street,” one middle-aged fisherman told OCCRP, adding that many have abandoned the job because they don’t have enough money to repair their boats.

Now only five remain, and they are “all the same age,” another chimed in. “In other words, there are no new fishermen.”

A damaged boat in the village of Morro de Puerto Santo in Sucre state, Venezuela.

This economic deprivation has made Güiria and other outlying towns fertile ground for criminal groups who, in addition to drugs, use the coast as a base for smuggling migrants fleeing Venezuela’s many crises.

In a small village in eastern Falcón, where homes are made of a patchwork of sheet metal and wooden planks, it is an open secret that irregular activities are carried out by people who, according to one local, “are not from here.”

At night, “the boys always see strange boats passing by with two engines sticking up. Around here there’s no fishing zone with boats that carry two engines,” the local told OCCRP.

These are “good boats,” they added. “Are you really going to be out fishing with a boat like that?”

A home in a coastal village in eastern Falcón state, Venezuela.

The description matches the type of vessels that appear to have been targeted by the U.S. strikes: speedboats outfitted with extra motors that allow them to reach speeds between 20 and 50 knots.

While they are relatively small, measuring usually between six and 15 -meters long, these vessels offer enough space to stash hundreds of kilos of cocaine and extra fuel drums to extend their range to destinations as far afield as the Dominican Republic, a key transit hub for U.S.-bound cocaine.

Engines for such boats are also easy to obtain and replace in the Venezuelan towns whose concrete piers are lined with weatherbeaten vessels.

"If one sinks or you lose it, its replacement is immediate," said Andrei Serbin, a security expert who heads a think tank that focuses on Latin America, Coordinadora Regional de Investigaciones Económicas y Sociales.

Crime Syndicates ‘Were the Authority’

According to Serbin, the state has retreated from outlying regions like Sucre and Falcón in recent years, leaving behind lower-level security forces who have become “complicit with the paramilitary groups.”

One fisherman from Sucre interviewed by OCCRP said that the local crime syndicates have become unofficial arbiters of justice in this vacuum. Instead of police, “they were the authority,” he said. “They would send for the culprit, investigate, take them away, and administer their punishments, the tortures they deemed appropriate."

Maduro and his regime spokesmen have long rejected accusations from the U.S. that he and other high-ranking officials are involved in drug trafficking themselves as part of the “Cartel of the Suns,” a term used by experts to describe a loose network of military and political actors who allegedly profit from the trade with the protection of the state. In a recent letter to the Trump administration, Maduro slammed the allegation as “fake news.”

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro speaks during a pro-government rally opposing U.S. President Donald Trump in Caracas on August 14, 2017.

Experts, however, question the sincerity of his government’s efforts to stem the flow of drugs surging through the country. In a 2024 report, Transparency International's Venezuelan branch found that a “lack of reliable public information” provided by government agencies, coupled with curbs on press freedom and “the use of propaganda in state-run TV stations,” make it difficult for civil society to evaluate the regime’s anti-drug policies.

While the production of cocaine has hit all-time highs and seizures of the drug have soared in many countries in recent years, Venezuela's figures have remained relatively stagnant: Over the past two decades, authorities have been reporting seizures averaging around 35 metric tons, year after year.

“The debate cannot continue to be reduced to how many kilos are seized, how many boats are destroyed, or how many human beings turned into drug mules rot in jail,” said Tablante, the former Venezuelan politician. “The question remains the same as we asked decades ago: Who protects? Who allows it? Who benefits?”

Michael Vigil, a retired agent who previously led the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s international operations, said the quantity of cocaine diverted through Venezuela is “higher” than what the country is reporting.

But he also criticized the Trump administration’s approach and described the recent strikes, which are part of wider military buildup in the region that has fuelled speculation Washington is seeking political change in Caracas, as acts of “political theater.”

“It’s going to have zero impact on the drug trade,” he said.

“The people on those boats are just really at the very low, low end of the drug trade. They're doing it because they're trying to survive.”