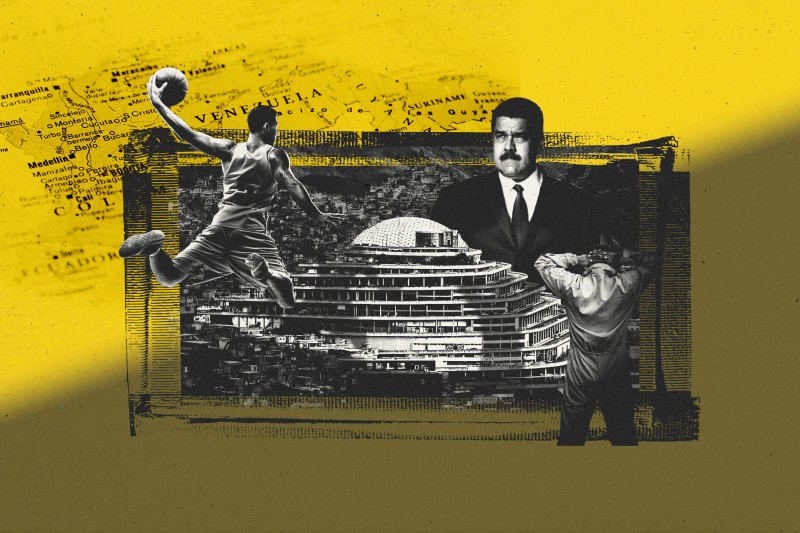

It’s a Saturday night in Caracas and the mood in the basketball arena is electric. The lights are dimmed, drums roll, a golden stream of fireworks explodes, and chants of “Vamos Pioneros!” (“Let's go, Pioneers!”) echo from the walls as the home team trots out in their bright orange uniforms, flanked by cheerleaders in orange dresses. The Pioneros del Ávila are here to play.

On the surface, tonight’s game looks like a normal professional sporting event — but there’s a dark side to this match. The basketball court where the Pioneros play their home games is located inside El Helicoide, one of the most notorious political prisons in Venezuela. A few floors down from where the cheering spectators are sipping beer and snacking on popcorn, more than 80 political prisoners are locked up in what rights groups say are horrific conditions.

The teams playing are part of Venezuela’s new “Professional Basketball Super League,” which was set up by the government several years ago with the stated goal of reviving the reputation of Venezuelan basketball.

But in practice, experts say, the Super League has become a playground for the regime of Venezuela’s authoritarian leader Nicolás Maduro and its allies, helping deflect attention from human rights abuses through what is known as “sportswashing.” In a brief report published earlier this year, Transparencia Venezuela called the new league “a network of influence that polishes the image of a repressive and opaque regime.”

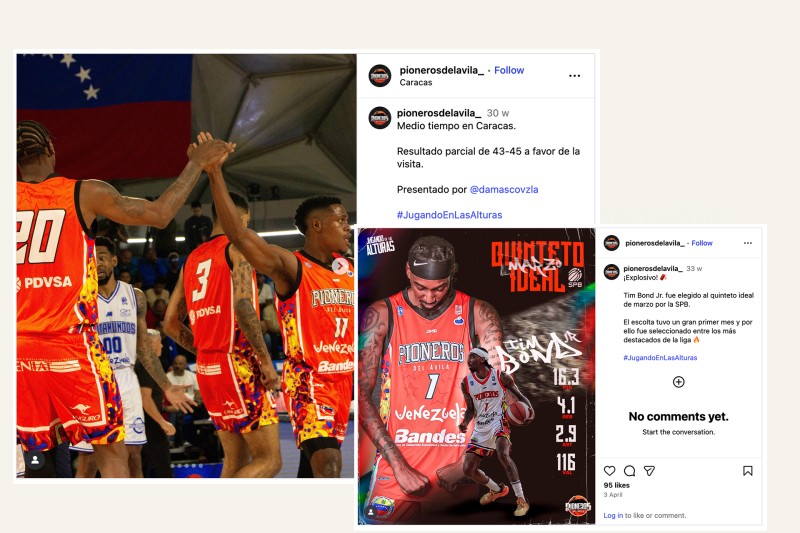

The Pioneros Del Avila (in orange) playing at El Helicoide in Caracas, Venezuela, on June 14, 2025.

“[This] is an attempt by the state and the security forces to position themselves in society, and that can’t be in favor of the values of sport,” said Jans Sejer Andersen, a sports journalist and founder of Play the Game, a Danish group that promotes fairness and sustainability in world sports.

At least two of the Super League’s 14 active teams are owned or effectively controlled by high-ranking security officials accused by the U.N. of human rights violations, OCCRP found after reviewing public documents and speaking to sources familiar with the inner workings of the league. There is widespread speculation that many of the other teams may also have ties to the government, although journalists could not confirm their ownership structures due to Venezuela’s lack of corporate transparency.

On the upper floors they’re playing basketball, and in the basement people are being tortured. I doubt such a thing exists anywhere else in the world.

Cándido Pérez, Venezuelan sports journalist

And to top it all off, last year it was announced that Super League games would be regularly played inside El Helicoide, to the consternation of human rights activists and others who oppose the Maduro regime.

Venezuelan sports journalist Cándido Pérez described the setup as “chilling.”

“On the upper floors they’re playing basketball, and in the basement people are being tortured. I doubt such a thing exists anywhere else in the world.”

OCCRP reached out to the Venezuelan government, the Venezuelan Federation of Basketball, the Super League, and several basketball teams, including the Pioneros del Ávila, asking for comment on the league and its ties to alleged human rights violations. None of them responded.

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro waves during Student Day celebrations at the Miraflores Palace in Caracas on November 21, 2025.

“These Places Are Built to Break Wills”

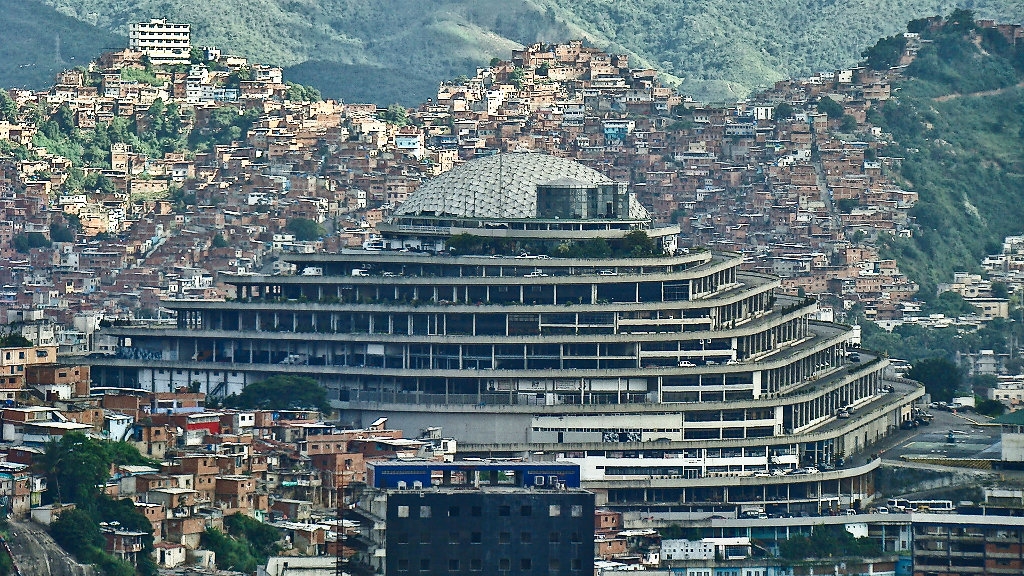

El Helicoide was once a symbol of Venezuela’s grand future.

In the 1950s, with Caracas awash in oil wealth and the dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez eager to show off his regime’s modernity, plans were laid for a huge, sinuous building that would house a luxury shopping center, complete with helipads and movie theaters. Even the name “El Helicoide,” or “The Helix,” reflects its innovative architectural design.

But El Helicoide was abandoned before it was fully constructed, after the fall of Perez Jimenez in 1958. After sitting empty for decades, occupied only by squatters, the vast space was converted, starting in the 1980s, into a headquarters for Venezuela’s national police and intelligence services — both of which have been accused of severe political repression and human rights violations. It also became a place for them to keep prisoners.

El Helicoide

The use of the space as a prison intensified under the governments of Hugo Chávez and his successor, Nicolás Maduro, and it became infamous after hundreds of young protesters who had demonstrated against their regimes were thrown into El Helicoide in the 2010s. The facility now holds dozens of political prisoners, including dissidents, journalists, and human rights activists, many of whom report having been tortured or mistreated inside, especially at the hands of Venezuela’s Bolivarian National Intelligence Service, known as SEBIN.

Demonstrators march during an anti-government protest in Caracas, Venezuela, on March 12, 2014.

The U.N.’s Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Venezuela, which monitors human rights in the country, has repeatedly highlighted “dire” conditions in El Helicoide, including torture with electricity, “brutal” beatings, and confinement in overcrowded cells without natural light or bathroom facilities.

Opposition politician Freddy Superlano has been detained there for over a year without trial, and has not been allowed to see his family or meet with a lawyer, according to his wife, Aurora. She told OCCRP that the only sign of life she receives is her husband’s used clothing, which is periodically handed over to her by prison authorities.

“I smell it and I know it is his,” she said.”

Venezuela’s former defense minister, Raúl Isaías Baduel, who was imprisoned multiple times after breaking with the Chávez regime, died inside El Helicoide in 2021 after being denied medical treatment, according to his family and human rights groups monitoring his case. (The Venezuelan government has denied this, saying that he died while being treated for COVID-19.) His son Josnars, who was imprisoned alongside his father, said he had personally been subjected to extreme torture, including being suspended from walls and having his testicles shocked with electricity.

“These places are built to break wills,” said Andreina Baduel, Raúl Baduel’s daughter.

Raúl Isaías Baduel and two of his children.

Current inmates include prominent human rights defender Javier Tarazona, who the U.N. found was beaten, suffocated with plastic bags, and locked up for 45 days with the light on 24 hours a day in a punishment cell, and journalist Carlos Julio Rojas, who has been detained in solitary confinement for months on end, according to a Venezuelan journalists’ group. (On November 17, the Venezuelan government allowed the journalist’s association to visit him after four months in isolation.) Lawyer and human rights advocate Rocio San Miguel has been held in the prison since February 2024, without the right to contact her lawyer. Her family has said she had a shoulder fracture that went untreated for several months.

But to the chagrin of advocates for these prisoners, the Pioneros del Ávila have also moved in. Their home court is a multi-story pyramid of gray concrete on top of El Helicoide known as “The Mountain.”

“For us, it’s deeply concerning that El Helicoide — a site of systematic torture — is being used as a tool to whitewash those responsible for crimes against humanity through sporting events,” said Víctor Navarro, a former political prisoner inside El Helicoide who now directs an NGO devoted to preserving the historical memory of those who were locked up there, in an interview with Efecto Cocuyo.

The people locked up inside El Helicoide know that basketball games are taking place above them, but cannot hear them through the facility’s concrete walls, according to a family member of one of the prisoners, who spoke on condition of anonymity due to security concerns.

Pioneers and Spartans

“The Mountain” was renovated and converted into a sports facility in 2022, according to local media, and renamed the Elio Estrada Paredes Gymnasium in honor of the commander-general of the Bolivarian National Guard.

Estrada Paredes was sanctioned in September 2024 by the U.S. Department of Treasury for his role in “repression of the Venezuelan people and denial of their citizens’ rights to a free and fair election.” He was also identified by the United Nations as part of the chain of command responsible for torture and mistreatment of prisoners in El Helicoide.

His namesake gymnasium’s home team, the Pioneros del Ávila, were founded in April 2024, and there is no publicly available information about who owns them, although their uniforms bear the logos of several government bodies that sponsor the team: the Ministry of Interior, the national oil company PDVSA, and Venezuela’s national tourism brand.

Images from the Pioneros del Ávila's social media pages show their uniform sponsors, including PDVSA and the Venezuelan Ministry of Interior.

The team’s publicly listed president is Adelis Pamela Peña Soto. Social security documents obtained by OCCRP show that she has been an official with the Bolivarian National Police since 2023.

But three different people who have been involved in the Venezuelan basketball community for decades — all of whom spoke on condition of anonymity due to fears for their security — told reporters that the de facto owner of the team is Rubén Darío Santiago Servigna, the commander general of the Bolivarian National Police, which is headquartered in El Helicoide along with SEBIN.

Santiago Servigna has also been sanctioned by the U.S., with the Treasury Department citing harassment and arbitrary detentions made by Venezuelan police in the aftermath of the 2024 presidential elections.

The police official did not respond to questions from journalists on his connections to the Pioneros del Ávila. But he is vocal about his passion for basketball — and the Super League.

"Right now, here at El Helicoide, not only is the National Basketball Super League being played, but a wonderful tournament is taking place, a tournament of the militia," said Santiago in a radio program he hosts, “The Rhythm of Security, with the Bolivarian National Police.”

“We have been fortunate to have the opportunity to be in the Super League, a Super League that is developing in the best possible way every day, despite all the obstacles, and today more than ever it is becoming one of the most important leagues in all Latin America.”

Rubén Darío Santiago Servigna promoting his radio program on Instagram.

Another new Super League team, which also plays at El Helicoide, is the Spartans Distrito Capital.

The Spartans, whose mascot is a chisel-jawed ancient warrior in a Roman helmet, are openly led by Leonel Alberto García Rivas, who acts as the team owner. He is the director of the elite special operations corps of the Bolivarian National Police.

Along with Santiago Servigna, García Rivas was identified by the U.N.’s International Fact-Finding Mission on human rights in Venezuela as part of the chain of command of special police groups that the U.N. said were actively involved in torture, arbitrary detentions, and enforced disappearances, as well as torture and ill-treatment, including sexual violence and other human rights violations, of political prisoners in Venezuela. In March of this year, García Rivas was sanctioned by the Canadian government for his links to human rights violations.

Unlike other Super Liga team owners, García Rivas publicly embraces his role and appears at public events linked to the Spartans. Earlier this year, he took part in a press conference at a Caracas restaurant where the team’s’ 2025 roster was presented to fans and the media.

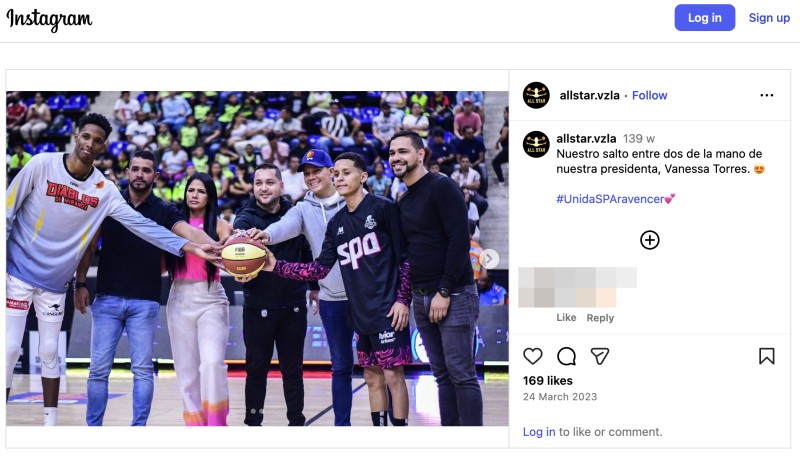

His wife, Qweany Vanessa Torres Toro, is the team’s president, according to its social media pages, and the face of many of its public initiatives, including basketball training clinics and the donation of balls and sports uniforms for underprivileged children.

Qweany Vanessa Torres Toro at center court ahead of a Spartans match in March 2023.

The team’s social media pages have frequently posted images of Torres Toro attending Spartan games and tossing up ceremonial jump balls at center court to start play. In one, from March 2023, she poses with her husband at the center of the court ahead of a match between the Spartans and the Diablos de Miranda. “Our jump, led by our president, Vanessa Torres 😍” the caption read.

A third Super League team also appears to have deep patronage links to Venezuelan intelligence. According to its social media page, the Gladiadores de Anzoátegui are officially owned by Fabián Carmine Eliantonio Gamboa, a regional pharmaceutical entrepreneur and government contractor.

Yet the Gladiadores wear the yellow-and-black logo of “Team Espartanos,” a sports collective that promotes soccer and extreme sports and is closely associated with Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Granko Arteaga, director of special affairs of the General Directorate of Military Counterintelligence (DGCIM). Granko Arteaga wears the logo of the Espartanos on his uniform sleeve, as do his subordinates. Media outlets in Spain and Venezuela have described him as founder of Team Espartanos, which shares a name with several other companies he reportedly owns, including a rum brand.

The DGCIM is one of the most feared security forces in Venezuela — and a major perpetrator of human rights violations, according to the U.N. fact-finding mission. For his own role in these violations, Granko Arteaga has been subject to personal sanctions since 2019 in the United States, the European Union and Switzerland. The sound of his name, according to the recent report on basketball by Transparencia Venezuela, “sends shivers down the spines of Venezuelan civil society.”

A New “Golden Age”?

There’s a basketball court or corner hoop everywhere you look in Venezuela, a reflection of the country’s love for the game — its most successful team sport on the international stage for decades. The Venezuelan men’s national team has qualified for five World Cups and two Olympic Games, and were crowned South American champions three times.

Venezuelans still speak with pride about the sport’s glory years in the early 1990s, when the national team finished second at the 1992 Olympic qualifiers to the legendary U.S. “Dream Team.”

Pérez, the sports journalist, said he and others recalled this era with deep nostalgia.

“You saw the Sunday or Saturday games, which were held in Caracas, packed to the rafters … wherever they were held,” he said. “And when it became professional, the whole business opened up and they earned very good money.”

Children play basketball on a court in Caracas, Venezuela, in November 2017.

Underpinning it all was the Liga Especial de Baloncesto, the country’s first professional basketball league, which was founded in 1974 by a sports journalist and promoter, and gave rise to several legendary teams.

But by the 2000s, economic decline and shifting political priorities began to erode the foundations of the Liga Especial.

“The problem was that financially, profits were declining, and so the quality of the [player] imports they brought in also declined, and in general the quality of the games was low, and some felt that the investment they had made was not paying off,” Perez explained. “So they gave up the teams, some sold them, some passed them to family members, but that’s what happened.

“That was the end of that golden age.”

Eventually, the government of President Maduro stepped into this void, and began tightening the links between the sport and the regime. In December 2019, Hanthony Coello, vice minister of Interior Policy and Legal Security at the time, was appointed the head of the Venezuelan Basketball Federation, a governing body that oversees the sport at all levels.

At a press conference to mark his appointment, he announced that a new “Basketball Super League” would be created the following year in an effort to revive the sport.

“We had some good decades of professional basketball, but times have changed, and we need to adapt to the new times, we need new ways of managing, we need to look to international markets,” he said.

The Basketball Super League started up in 2020, with 13 teams. Some were respected clubs with long track records of success, like the Caracas Crocodiles and Carabobo Globetrotters, but the league also came to include several new clubs, including two that now play at El Helicoide: the Pioneros, and the Spartans Distrito Capital. (In 2022, the league’s composition was slightly adjusted and its name changed to the Professional Basketball Super League after it merged with another league.)

The league has successfully recruited a number of international players, including U.S. college basketball veterans and even two former NBA players, Dwight Buycks and Hollis Thompson.

Coello, who is now a ruling party congressman, has remained closely tied to the Super League, regularly showing up at matches and attending the league’s annual meeting last year as an honored guest. He did not respond to a request for comment.

The FIBA Connection

Although it is unclear how much organic support the Super League has, its games are widely broadcast on Venezuelan public television and admission is free, which ensures that the stands are always full. At the game in June attended by reporters, spectators queued for up to two hours to get a red armband that provided free admission to the basketball stadium.

The place filled up quickly to full capacity: In the aluminum bleachers, people squeezed together, perching their children on their laps to make more room, as the orange-clad Pioneros faced off against the Carabobo Globetrotters.

But above it all, at the very top of “The Mountain,” hangs a large poster with three huge faces that serve as a constant reminder of presence of the Venezuelan regime: the late strongman Hugo Chávez and his successor, Maduro, alongside Venezuelan hero Simón Bolívar, whose mantle Chávez claimed to have taken up.

Large white letters at the bottom of the poster read: “Command by obeying the people.”