“Men came out of nowhere and pointed a gun at my uncle and just took my cousin,” she told OCCRP.

The Garcia family had just become the latest victims in kidnapping for ransom in Michoacan, a growing criminal enterprise in the region.

Desperate, Garcia’s family put up fliers and posted pleas for help on Facebook. Two days later, the kidnappers named their price. The family was able to scrape together the money to pay for the teenager’s safe return, but that was far from the end of it.

“My family, including my mom’s brother, started receiving phone calls from the men saying they had his daughter, which wasn’t true. They were doing that to scare them and get more money out of them,” Garcia said.

The calls even extended to Garcia’s family in California -- where she lives.

“To be honest, it makes me feel angry, sad and terrified for those who live there (in Michoacan), especially my family,” she said.

Migrants, most of them asylum seekers sent back to Mexico from the U.S. under the "Remain in Mexico" program officially named Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), wait in line to receive bottles of drinking water by a makeshift encampment in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico, October 28, 2019 (REUTERS/Loren Elliott).

Migrants, most of them asylum seekers sent back to Mexico from the U.S. under the "Remain in Mexico" program officially named Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), wait in line to receive bottles of drinking water by a makeshift encampment in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico, October 28, 2019 (REUTERS/Loren Elliott).

Michoacan has become infamous for the violence surrounding the control of its lucrative billion-dollar avocado industry. It is also known for its opium and marijuana production, starting in the 1960s, before a more recent shift to amphetamine and fentanyl.

And there is the occasional ransom gig, like Garcia’s family endured, for quick cash.

Garcia’s saga is just one example of the kind of violence and uncertainty people in Michoacan and Mexico are increasingly having to contend with.

Mexico’s president has increasingly faced criticism for his government’s non-confrontational approach to combat cartels, with rising acts of violence plaguing the country.

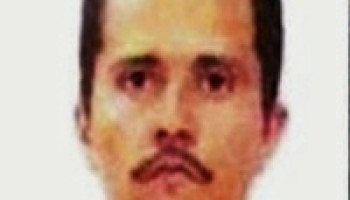

With that softer approach towards organized crime, experts believe one cartel boss is making a play to control his home state: Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, more commonly known as “El Mencho, and the head of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel.

Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, source: US State Department.Falko Ernst, a senior analyst covering Mexico for the International Crisis Group, told OCCRP that El Mencho considers the area his “birthright” and has been trying to seize it for the past eight years.

Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, source: US State Department.Falko Ernst, a senior analyst covering Mexico for the International Crisis Group, told OCCRP that El Mencho considers the area his “birthright” and has been trying to seize it for the past eight years.

“It’s his home turf. It’s not only about militants taking over commodities, it’s personal,” said Ernst. “When he left, he was a nobody.”

Ernst doubts El Mencho would be welcomed back to the community with open arms, considering the length of time the alleged kingpin has operated outside of the region.

His attempts to retake his home state have mobilized local gangs, several of whom have joined forces and formed a “Michoacan front” to fend him off.

Ernst says the attack and slaughter of 13 police officers on Oct. 14 was designed to be seen by the media, the general population and El Mencho’s rival gangs.

The bodies of the police officers were left on a paved road next to their burned vehicles 12 kilometres from where the reputed drug lord was born.

“What we’re seeing, in spectacular ways, is what has been going on for the better part of a decade,” Ernst said. “What’s more likely is … we’ll see a continuation of this violence.”

Relatives of a police officer, who was killed along with other fellow police officers during an ambush by suspected cartel hitmen, react during an homage organised by the state government, in Morelia, in Michoacan state, Mexico October 15, 2019 (REUTERS/Alan Ortega).

Relatives of a police officer, who was killed along with other fellow police officers during an ambush by suspected cartel hitmen, react during an homage organised by the state government, in Morelia, in Michoacan state, Mexico October 15, 2019 (REUTERS/Alan Ortega).

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration calls the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, or CJGN, the most violent cartel in the world, describing a series of beheadings and violence orchestrated by its members.

“I think in general terms, CJGN has moved from the fastest growing drug threat to the number one drug threat in Mexico,” Special Agent Kyle Mori told OCCRP in an interview.

The cartel largely controls 23 of Mexico’s 32 states, “as well as most of the drug routes into the US and in most continents around the world, except for Antarctica,”

he said.

Mori, who has participated in investigations of the CJGN and El Mencho for several years, says he doesn’t believe the drug kingpin’s rumored return to Michoacan is something new.

“As far as talking drug routes, I think Mencho and the CJGN have controlled drug routes and smuggling for the last six years (in Michoacan),” he said, adding he couldn’t comment on speculation regarding El Mencho’s physical movements.

But the questions remain: What can be done about the cartel wars, and how can Mexico ensure a normal life to its citizens?

In late October, about 56 percent of citizens polled by Mexico-based newspaper “Reforma” say they believe organized crime is more powerful than the government.

The poll came in the wake of a failed military firefight with members of the Sinaloa Cartel while attempting to arrest Ovidio Guzman, the son of the infamous boss El Chapo.

Despite arresting Guzman in Culiacan, the military had to give him up after being surrounded by hundreds of Sinaloa cartel gunmen. Authorities had to completely withdraw from the city.

The defeat and the resulting violence in Culiacan sparked outrage at Mexico’s military and government.

Ernst says the government’s stance of not combating cartel violence with the military could allow the situation in Michoacan to spin further out of control, as armed groups test how far they can push authorities.

For the average resident, living in any of the regions engulfed by gang violence is like living in a war zone.

Links to the cartel, no matter how tenuous, can be enough to get you killed.

Jenny, an American with family living in Michoacan, says two of her cousins were seized by a cartel a year ago.

“One of them was involved with a drug cartel,” she told the OCCRP, requesting her last name not be used. “When the cartel went to look for him, they saw him with his brother, who was innocent and not involved with the cartel.”

The two have been missing ever since.

“By missing, we mean they’re probably dead,” Jenny said.