Reported by

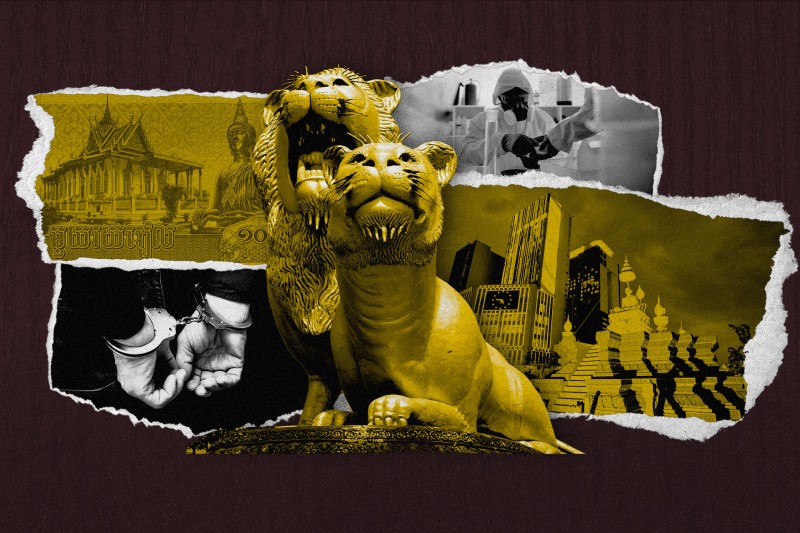

Cambodia is a global epicenter for scam centers, home to one of the biggest synthetic drug labs ever detected, and its citizens have been involved in an array of Southeast Asia’s most infamous — and lucrative — transnational crimes. Meanwhile, “corruption and official complicity” enables “endemic” human trafficking involving tens of thousands of victims, according to the U.S. State Department.

Cambodia’s government, which did not respond to questions from OCCRP, has launched a crackdown on scam factories and says it has made thousands of arrests. It also signed agreements to strengthen anti-money laundering measures last year. Even so, international observers remain concerned.

Last weekend, China’s embassy in Cambodia said its ambassador had met with senior Cambodian ministers to protest the disappearance of its citizens in the country. The ambassador urged the Cambodian government to “ take concrete measures to severely crack down on crimes such as illegal detention and violent assault against Chinese citizens, as well as online fraud activities.”

“We've been increasingly concerned about the power and influence of organized crime in Cambodia, and its regional and global impact,” Jeremy Douglas, deputy director of operations at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), told OCCRP. “It's become a safe haven in recent years and the state hasn't stepped in, or won't.”

How did it come to this?

Buddhist monks walk down a dirt road in front of new construction in Sihanoukville, a port city in Cambodia's south that has become the epicenter of a huge gambling and scam center boom over the past decade.

Democratic Hopes Dashed

At the end of the Cold War, Cambodia was hailed as a shining light of democratic promise in Southeast Asia. An estimated 1.7 million people, or one fifth of its population, had been killed under the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime in the 1970s and the country was later racked by civil war. But a peace deal brokered in Paris in 1991 ended the violence and ushered in elections and a democratic constitution.

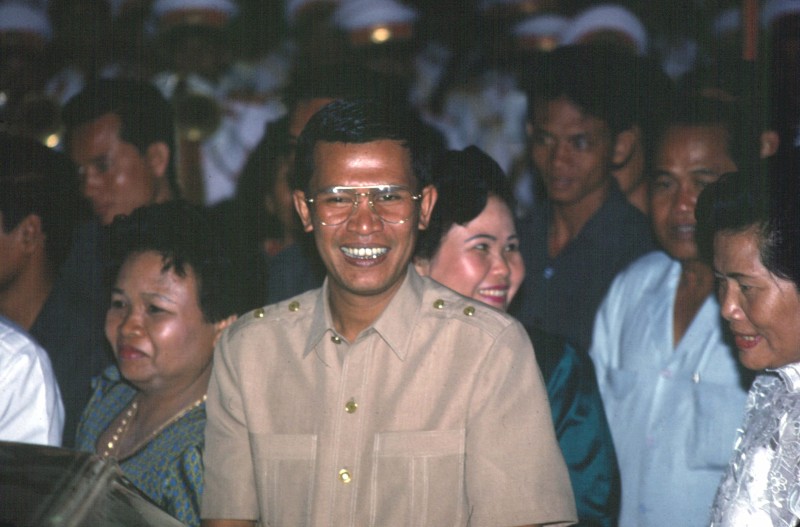

Cambodia’s lurch toward authoritarianism began right after the 1993 election, when its ruler Hun Sen refused to accept defeat in the polls, instead becoming co-leader in a compromise deal before a coup in 1997 elevated him to sole prime minister. He would continue leading the country until 2023, when he finally relinquished power — to his son, Hun Manet. By that time, Cambodia’s opposition had been outlawed, its leaders imprisoned, and many independent media outlets shut down.

Hun Sen in 1991.

Hun Sen announcing on July 26, 2023, that he would resign after 38 years as prime minister and pass power to his son, Hun Manet.

“Corruption goes hand-in-hand with authoritarian regimes built around an individual or family. It allows the ruler to combat any internal threat to their power from political, military and business elites,” said Lee Morgenbesser, an associate professor of comparative politics from Australia’s Griffith University. “The logic is simple: the ruler provides an umbrella of protection for illegal activity, in return for loyalty from various elites."

“It’s a cesspool and the cesspool gets bigger over time as new people are drawn in.”

Corruption goes hand-in-hand with authoritarian regimes built around an individual or family.

Lee Morgenbesser, professor, Griffith University

Patronage Networks Evolve

As Hun Sen settled into autocratic rule, he began to build a patronage network which tied business interests to political power. A small group of tycoons with political, business and family links to the ruling family and other senior government members was granted concessions to log forests and extract minerals, Global Witness found in a landmark 2007 report, "Cambodia's Family Trees."

The most powerful logging syndicate at the time was led by Hun Sen’s cousin and included the brother-in-law of the minister of agriculture, forestry and fisheries, the Global Witness report said. The ties were so tight that some of the tycoons also became senators for the ruling Cambodian People’s Party, further entrenching the network. By 2012, five of these tycoon-senators held 20 percent of total land allocated through concessions, amounting to more than half a million hectares.

The entrance to the Cambodian Senate headquarters in 2016.

Since then, Cambodia’s patronage networks have widened to include China-born citizens who face criminal allegations abroad, and have gained Cambodian nationality.

“The profits from transnational organized crime have become intertwined with Cambodia’s longstanding patronage system,” said Neil Loughlin, a Southeast Asia expert from City of London University.

Chen Zhi, the head of Cambodia’s Prince Group and a major business figure in the country — until he was arrested and extradited to China last month in the wake of sweeping U.S. sanctions — was appointed to the privileged position of “oknha,” or “lord,” in 2020.” He has also been an adviser to both Hun Sen and Hun Manet.

Cambodia’s Interior Minister, Sar Sokha, has also come under scrutiny for his role as the founding director, alongside Chen Zhi, of one of the companies in the Jin Bei Group. Jin Bei was sanctioned by the U.S. for its alleged role in hosting the Prince Group scam centers and engaging in human trafficking. Sar Sokha — who took over the position of Interior Minister from his father in 2023 — ceased being a director of the company in August 2018 and has denied he has any investments or links to Jin Bei.

Cambodia has cancelled Chen Zhi's passport and extradited him to his home country of China.

Hun To, the nephew of Hun Sen and cousin of Hun Manet, was a director of Hui One Pay PLC, which was sanctioned earlier this year by the U.S. Treasury for its role in transferring the proceeds of cyber crime, including directly working with North Korean officials to launder the proceeds of cyber heists. The Cambodian government shut down Hui One in December.

Hun To remains chairman of Lixin Development Co Ltd, a key company in the Lixin Group, which an OCCRP investigation this week revealed has been linked to scam centers in Sihanoukville and apparently illegal gambling operations. (Hun To has not been sanctioned or implicated in any wrongdoing.)

Cash for Citizenship

Cambodia’s “payment-for-passports” citizenship scheme has underpinned the penetration of crime groups into the country. Adopted in 1996, Cambodia’s Law on Nationality offers citizenship in exchange for donations and investments of at least 1 billion riel ($246,00 Cambodia ) or 1.25 billion riel ($308,000), respectively. As well as gaining Cambodian passports, new citizens can take new names.

“With new identities, criminals can cross borders freely, set up companies and move assets,” Jason Tower, a Southeast Asia crime expert who now works at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, told OCCRP in 2024.

This week, OCCRP revealed that a Taiwan-born methamphetamine manufacturer evaded a 12-year jail sentence in his homeland by fleeing to Cambodia, taking citizenship and changing his name to Thomas Xu.

Xu then used his new identity to invest in Georgia and attend high-profile events held by Cambodia’s Lixin Group alongside politicians and business tycoons in both countries.

Cambodian citizens sanctioned by Western governments, under investigation by China, or both include Chen Zhi, the Prince Group tycoon; Dong Lecheng, an aviation mogul the U.S. Treasury Department said was linked to online scam centers; and She Zhijiang, an illegal online gambling magnate who was extradited from Thailand to China in November. All were born in China, but secured Cambodian passports as they built up their empires there, enabling them to take advantage of the country’s patronage networks and weak law enforcement.

Nine of the 10 people convicted by Singapore authorities for their role in a $2-billion money laundering syndicate in 2023 were also born in China and acquired Cambodian citizenship.

In the wake of the publicity about the Chinese-Cambodians involved in the Singapore-based gang, Cambodia’s government stopped publishing the names of new citizens in the royal gazette.

“Now that this data is secret, it is much easier for criminals to use these passports to evade arrest,” Tower added.

From Casinos to Scam Centers

While the Cambodian passport scheme gave alleged criminals mobility, a new seam of opportunity was opening up in Cambodia for organized crime as casinos boomed.

The Cambodian government dramatically increased casino licenses starting in the mid-2010s, and the port town of Sihanoukville was quickly transformed into a gambling mecca for predominantly Chinese tourists.

A casino under construction in Sihanoukville in 2018.

Meanwhile, the Naga World casino in the capital Phnom Penh expanded rapidly thanks to customers funneled to it by Suncity, the junket operator led by Alvin Chau. Chau was later sentenced to 18 years in prison following a Macau court finding that he headed a criminal syndicate involved in illicit gambling and fraud.

“Junkets were the primary modality for laundering money through land-based casinos [in Cambodia]. They were the cornerstone of a massive underground banking system,” said John Wojcik, senior threat researcher for Asia at Infoblox Threat Intel.

Operators also set up online casinos servicing gamblers who could place bets on their phones and computers in real time with dealers streamed live from a casino floor.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020, seriously curtailing international travel, junket operators collapsed, forcing organized crime groups to search for new sources of revenue and labor, according to the UNODC.

“They doubled down on online casinos and cybercrime,” said Wojcik.

Casino premises and hotels, now devoid of patrons, were used to host scam centers and the labor problem was addressed by trafficking workers from around the world and forcing them to undertake the fraud schemes.

“Dormitory-style bedrooms were constructed in the complexes; scammer training manuals were created; enforcers were hired to control trafficking victims; and the mass recruitment of trafficking victims began,” the UNODC said.

Massive Scam Operations Target Victims Worldwide

Fueled by the rise of cryptocurrencies and digital payments systems, scam compounds and online betting platforms have thrived in Cambodia, targeting victims worldwide. Across Southeast Asia, the UNODC estimated last year that the fraud farms generate $40 billion in annual profits.

It's clear that the accelerating scale, sophistication and reach of Cambodia-based crime groups is overwhelming law enforcement and criminal justice systems around the world.

John Wojcik, senior threat researcher, Asia at Infoblox Threat Intel

A figure for the contribution of Cambodia-based scam centers was not provided by the UNODC but recent U.S. enforcement action against Prince Group highlighted the scale of the country’s involvement.

The U.S. Department of Justice filed a forfeiture complaint to seize $15 billion of bitcoin allegedly linked to Chen Zhi. The indictment against him quotes a Prince Group co-conspirator as boasting that Prince earned $30 million a day from scams, almost $11 billion a year. The group had “billions in financial flows” and made a “particularly significant” contribution to the $10 billion lost by Americans last year to Southeast Asia-based scams, the U.S. Treasury Department said.

“It's clear that the accelerating scale, sophistication and reach of Cambodia-based crime groups is overwhelming law enforcement and criminal justice systems around the world — and rapidly outpacing governments’ ability to contain the situation,” said Wojcik.