Reported by

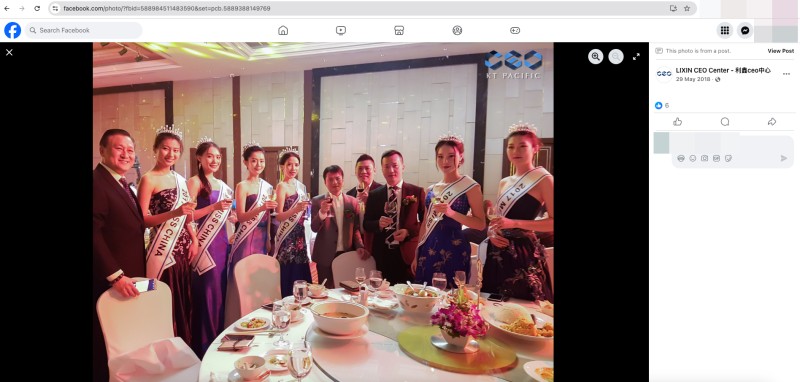

Surrounded by beauty queens and drinking red wine, the Hsu brothers toasted the groundbreaking of a 33-story luxury development in Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh in May 2018.

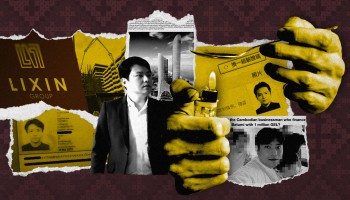

It was the first big property deal for the Lixin Group of companies, owned by the older of the two Taiwanese brothers, Hsu Ming-chao. Over the next few years, it would expand into a sprawling conglomerate with interests in biotech, e-commerce, events management, publishing, and more.

The Hsu brothers celebrating the groundbreaking of a luxury property development in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in May 2018.

Lixin now claims to hold 35 million square meters of land, and is even building an entirely new city in the southwest of Cambodia.

But underneath Lixin’s seeming runaway success lies a more complicated story.

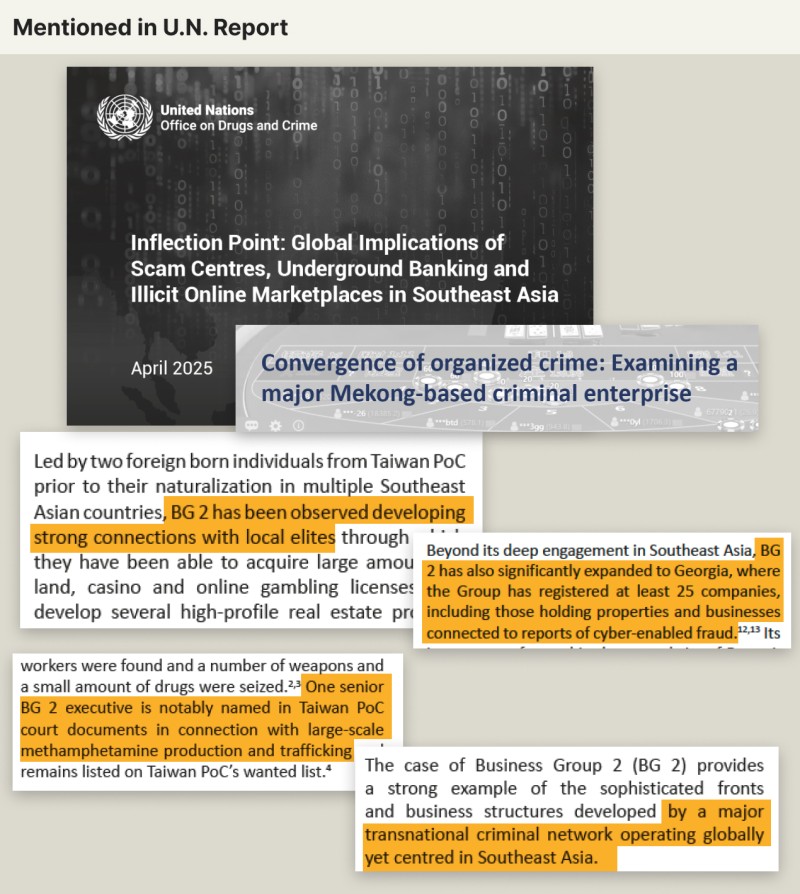

A United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) report published in April 2025 featured a case study on a “major Mekong-based criminal enterprise” which it identified only as “Business Group 2.”

Citing law enforcement sources and court documents, the UNODC report said that Business Group 2 had an “expansive portfolio of interests in land-based and online gambling, cyber-enabled fraud operations, and large-scale drug trafficking.”

Multiple sources involved in preparing the report, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were discussing confidential U.N. matters, confirmed to OCCRP that “Business Group 2” referred to Lixin Group.

Excerpts from the April 2025 UNODC report.

A Lixin Group representative, Grant Tao, said the company was unaware of the report, but strongly denied any wrongdoing or involvement in illegal gambling or cyber-fraud.

“If the client confirms that BG2 in the U.N. report is alluding to Lixin Group, the client will contact the relevant U.N. departments and submit relevant evidence to explain the situation and clarify the facts,” he told OCCRP.

Previously unreported Chinese court judgments obtained by OCCRP provide evidence of a scam operation in Cambodia run by an entity called “Lixin,” which siphoned its proceeds into real estate.

According to the two court judgments, Chinese employees of Lixin wooed victims on social media and enticed them into chat groups, where other fraudsters then posed as successful investors. Those who invested in the syndicate's bogus stock and crypto schemes would either see their money siphoned off directly or frozen for fabricated reasons.

Other victims, according to a defendant’s confession cited in one of the judgments, were lured to join fake gambling platforms, which were rigged to ensure they would lose their money after an initial winning streak.

Testimony from defendants and witnesses cited in both court judgements detailed a sophisticated operation, with various departments set up by the company called “Lixin,” including a business department that assigned workers to “sub-groups” and a logistics department that procured fraud tools. A property department, meanwhile, invested the illicit earnings into real estate developments in Cambodia and other overseas investments. It was, said one court judgment, “an attempt to legitimize the proceeds of crime.”

China has no jurisdiction over Lixin since it is based in Cambodia, and Lixin itself was not accused in the cases, but one of the judgements described it as a “foreign fraud syndicate” that “practiced telecommunications network fraud.” The Chinese court ultimately found 16 former Lixin employees, all Chinese nationals, guilty of telecommunications fraud. The court also found that victims who testified in the case had been cheated out of about 10 million RMB ($1.4 million at today’s rates). No record of an appeal was found in China’s digital court records system, China Judgements Online.

The relatively small losses identified in the cases is dwarfed by the size of Southeast Asia’s scam industry today. A different UNODC report found that scams generated up to $37 billion in losses for its victims in East and Southeast Asia in 2023, with a “predominant proportion” of the losses caused by Southeast Asian organized crime groups.

Lixin’s lawyers denied it was the company cited in the Chinese court cases, saying that proceedings related to “individuals, scam methods, fund flows, and site references in these cases have no connection whatsoever to Lixin Group.”

Even so, many of the defendants and trial witnesses used the name “Lixin” to describe the “fraud ring” they had joined.

In testimony cited in one of the judgments, several of the accused said they worked inside a Sihanoukville office building referred to as "Lixin 3rd Building." Later, one witness said, the scam operation moved to an upper floor of a building called “Harbor City WM Casino.”

According to the UNODC report, “BG2” had invested in a “large business park” in Sihanoukville where “multiple raids … have resulted in rescues of people claiming to be detained there and forced to engage in online crimes.” Multiple sources involved in compiling the report said this referred to Lixin Harbour City, a sprawling compound that made headlines in August 2022 when local media reported it had been raided by Cambodian police. The police found 35 trafficked workers in the building and arrested a manager working in one of Lixin Group’s buildings, the reports said. OCCRP could not determine if formal court proceedings were ever opened after the arrests, and Cambodian government and court officials did not respond to questions on the case.

Tao, the Lixin representative, told OCCRP that the Lixin Harbour City compound had been developed by Lixin, but that the group was “never involved in project operation and management” at the site. He also denied the compound had ever been raided.

Lawyers for Lixin did confirm that Hsu Ming-chao — the main shareholder in the companies that make up Lixin — was an investor in WM Casino, also mentioned in testimony during the trial.

The WM Casino in Sihanoukville, pictured here in 2020 after the online gambling ban went into effect in Cambodia.

Online Casino Pioneers

As the sleepy seaside Cambodian city of Sihanoukville transformed into a glitzy gambling mecca for Chinese tourists in the mid-2010s, Lixin Group was quick to get in on the action. In 2017, it launched the WM Hotel & Casino near the city’s center.

From the outset, it offered both in-person and online gambling, with a roped-off area set aside for studios where dealers took bets in real time from gamblers watching on their phones or computers.

By 2018, Hsu Ming-chao was selling online gambling software at a trade fair in Macau, showing off WM’s casino studio setup and apps. The event featured an appearance from Jacky Wu, a Taiwanese TV host and singer. (Wu’s agent told Taiwan’s The Reporter, an OCCRP partner, that the singer had simply been “invited to perform at the event” and had no other ties to Lixin.)

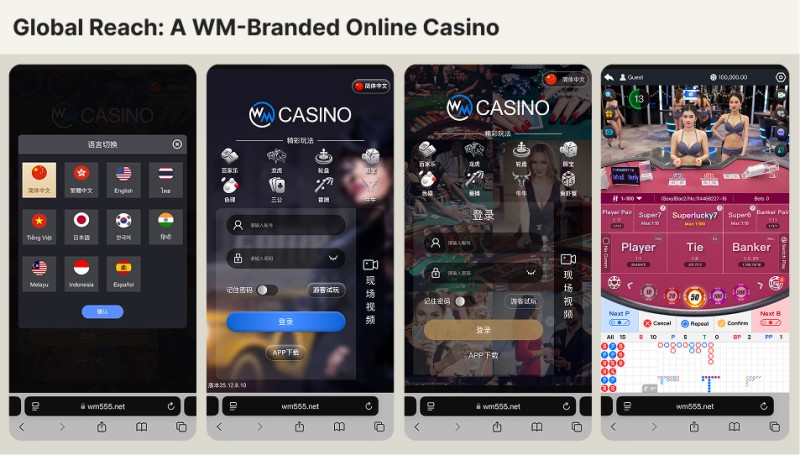

Tao, the Lixin representative, denied the company had developed “any online gambling software”, or provided “gaming software to any gambling website,” but the UNODC report noted that “BG2” provided its software to “hundreds of licensed and unlicensed online gambling websites.” This coincides with a 2018 raid in Taiwan’s Kaohsiung City, Hsu’s hometown, during which police discovered a room full of servers supporting WM gambling websites, among others.

By late 2019, Cambodia’s then-leader Hun Sen had announced the government was banning online gambling operations on its territory, following complaints from the Chinese government.

Despite the ban, reporters found at least nine online gambling websites and apps that used WM’s branding or linked to WM-branded casino sites as of November 2025. One WM app offered gambling in 11 different languages.

Screenshots from an active online casino using the WM branding.

According to documents provided by Lixin’s legal team in response to OCCRP queries, Hsu Ming-chao exited an investment agreement underpinning the WM casino project in December 2019. The venture was loss-making, the lawyers said. However, documents reviewed by OCCRP show Lixin Construction Co. Ltd — whose sole shareholder and director is Hsu Ming-chao — applied to the Cambodian Ministry of Commerce to register trademarks for WM Casino, WM Hotel and Lixin Casino in July 2020, after his lawyers said he divested from the casino business. A Cambodian trademark holder has exclusive rights to use the name and logo, and can license it to others for payment or stop unauthorized use of the brand.

In subsequent correspondence with OCCRP, Lixin lawyers said the trademark applications were “made as part of our client’s overall business plan,” without going into further detail.

All the applications were granted, although two and a half years later they were challenged by Starwood Hotels & Resorts and the status of the trademark application is currently marked “pending” in the World Intellectual Property Organization database. The challenge was based on the similarity of the WM brand to that of Starwood’s luxury W Hotel chain.

A spokesman for Marriott hotels, which owns Starwood, confirmed the trademark challenge. “This is a routine trademark registration dispute, which we understand remains ongoing. Marriott International does not currently have any relationship with Lixin Group or business operations involved in the WM Casino project.”

The WM Casino building in 2020.

When OCCRP reporters visited Sihanoukville in 2024 and 2025, they found evidence of an online casino still running in the building that formerly housed WM Hotel & Casino, although it was in considerable disrepair. (Lawyers for Lixin denied that the group was involved in this casino.) Every hour or so, young women would alight from vans before entering a side door guarded by a security guard, some wearing distinctive black-and-white dresses. Hours later, journalists saw several female dealers wearing the same dresses on the gambling apps featuring WM’s branding.

A Cambodian woman working as a dealer inside the WM building told reporters there were 50 or 60 live dealers there. For a shift that started at 3 p.m. and finished at 11 p.m., she said dealers earned $600 per month, above the average Cambodian wage, as well as free accommodation. A grocery stand seller working nearby also said there was a casino inside the building, which operated online.

During a second visit to the building in late November 2025, a reporter observed SUVs and 25-seat buses transporting female workers to the compound, which now has “FODUNA CASINO” emblazoned on its facade. OCCRP was unable to find a public entrance to the building and, according to two nearby vendors and two tuk-tuk drivers, the casino does not allow walk-in gamblers.

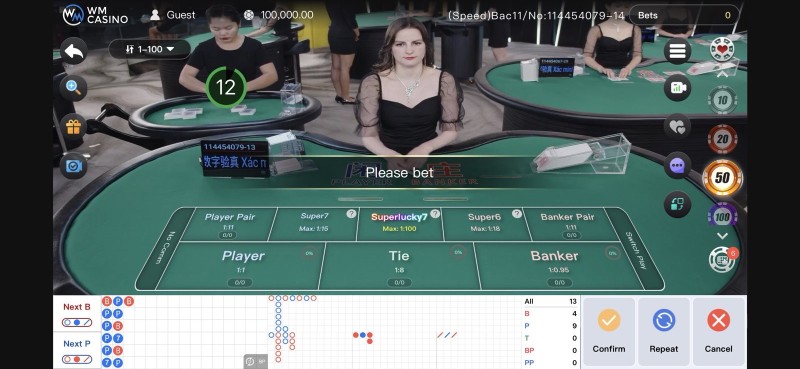

A review of the WM casino app, meanwhile, showed that two workers first seen working as live dealers in July 2024 were doing the same job in similar surroundings in December.

A screenshot from a WM Casino-branded gambling app taken in December 2025.

A New Sihanoukville?

Sihanoukville today is a shadow of its former self. Most of the Chinese tourists and many workers have vanished due to the gambling crackdown and Chinese government restrictions on travel, while the construction cranes have mostly gone. Half-built apartment blocks and rubble-strewn vacant lots dot the city.

But Lixin is planning a massive development nearby that could supplant the ravaged city altogether: A hugely ambitious project to build a 2,500-hectare metropolis dubbed Sihanoukville New City.

Hun To — the cousin of the country’s current prime minister and nephew of Hun Sen, the former leader — is heavily involved, corporate and government records show. The firm Lixin Development, co-directed by Hun To and Hsu, is one of the major partners in the project. A second Lixin company has also invested.

The development includes a business district with a skyscraper, hotels, a logistics hub, a technology park and expansive residential areas. For tourists, there will be world-class hotels, casinos, an eco-resort, a top quality golf course, a theme park, and a horse racing track.

A visit to the site last year by OCCRP showed vast tracts of land have been cleared and new roads and roundabouts constructed.

Since that visit, an integrated resort consisting of two towers of accommodation and a casino has opened in the precinct, with the hotel already taking bookings, its social media accounts say.

The city will be, according to a Lixin promotional video, “a Cambodian version of Shenzhen,” the Chinese mega-city that had just 300,000 residents in 1980 and is now a trading hub that boasts a population of 17 million people.

Speaking at an event in August 2019, Hsu said the city would be a model for others in Cambodia and across the region, according to media reports.

"Lixin Group would like to thank Prime Minister Hun Sen and the Cambodian government for giving our group such a good opportunity,” he said.