Corrado Catesi, the Coordinator of Interpol's Works of Art unit, explained that museums became prime targets for thefts after various countries’ stay-at-home policies made burglarizing private residences all but impossible.

“Criminals were forced to find other ways to steal, illegally excavate and smuggle cultural property,” Catesi said.

This is how the pandemic “had a significant impact on criminals involved in the illicit traffic of cultural property but did not in any way diminish the demand for these items or the occurrence of such crimes,” he said.

The Interpol report analyzes data provided by 72 member states on cultural property crimes, arrests, and trafficking routes in 2020, when a total of 854,742 cultural property objects were stolen.

This can include anything ranging from coins and medals to paintings, sculptures, archaeological items, or archival materials.

Some notable examples, according to Interpol, include the theft of three masterpieces from the Christ Church College in Oxford, U.K.; as well as the theft of a Van Gogh painting from the Singer Laren museum in Amsterdam.

Numismatic, archaeological, and paleontological items have higher reported seizure rates than other cultural objects, according to the international police agency.

This is attributed to the fact that it can be difficult to trace an object’s origin outside of its local environment, which makes it burdensome for law enforcement agencies to properly identify the cultural property as stolen.

Whereas most law enforcement agents are beginners when it comes to identifying cultural property, the criminal middlemen who illicitly transport them from one country to another are usually experts in the object’s field of study.

Interpol reported that such middlemen play a vital role in established criminal networks that profit off of selling stolen or illicitly excavated objects across borders, regions, and continents to foreign collectors.

Intelligence gathered in the report outlines how they often work on commission, both for crime groups that operate by stealing as many objects as possible as well as those who exclusively seek out highly prized objects for collectors who cannot otherwise purchase them legally.

Such groups, however, do not operate exclusively in the shadows.

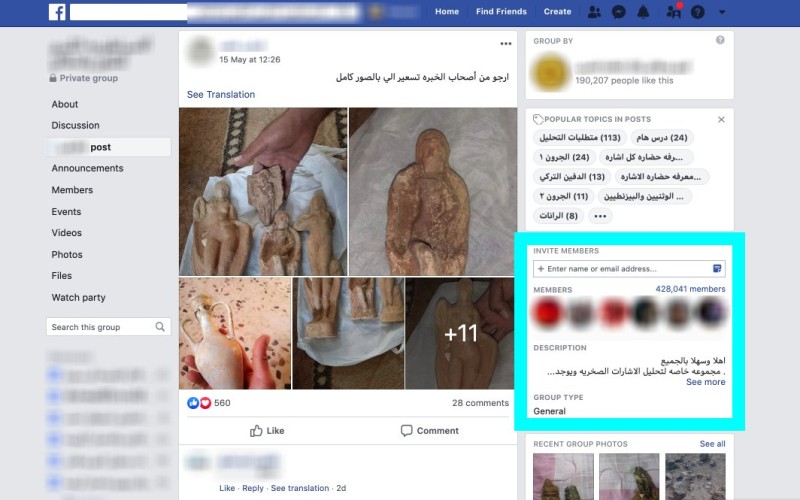

Katie A. Paul, Co-Director of the ATHAR Project, which investigates the digital underworld of antiquities trafficking, said that social media platforms are widely used to propagate these illicit markets.

One Facebook group, which they’ve discovered to be a black market site for antiquities, has as many as 300,000 members and has been growing rapidly throughout the pandemic.

“It’s also important to note that this is not isolated to Facebook,” Paul said. “Platforms like YouTube monetize videos for content creators, which means that looters can profit from the destruction of a [archaeological] site even if they don’t make a sale.”

Paul notes that the power of social media has exacerbated the challenges in keeping a lid on such black markets. “Facebook has over two billion users globally so users will cross-platform their content by posting monetized YouTube links into Facebook antiquities trafficking groups, thereby driving users to their content,” she says.

Using a series of maps and graphs, the Interpol report outlines how cultures across every region of the world are hurt by the illicit theft and trafficking of their historical objects. More than half of these objects – 567,465 according to Interpol – were reportedly seized in Europe alone.

Furthermore, given the transnational nature of organized crime, all regions have been observed to simultaneously be areas of origin, transit, and destination for stolen cultural property.

Interpol is now developing new methods to educate law enforcement agencies in how to take on this particular transnational organized crime threat.

One example is the Stolen Works of Art database, available to both law enforcement officers and the general public in order to identify culturally significant historical items. The database reportedly holds a record of more than 52,000 objects from 134 countries.

Another is the ID-Art mobile application. Launched in May earlier this year, the app grants users “access to the Interpol database, creates an inventory of private art collections and reports cultural sites potentially at risk.”

The app has already aided investigators in bringing cultural property crime cases to a close, the agency said.

In one instance, a tip-off in London allowed Spanish National Police to recover three Roman Empire-era gold coins worth an estimated 200,000 euros (US$232,710), which were stolen in Switzerland in 2012, as well as arrest the two perpetrators attempting to sell them on the black market.