When Nicaraguans head to the polls this week they will find a ballot card clean of serious challengers to President Daniel Ortega, after a months-long crackdown that has targeted opponents of his authoritarian regime.

Since June, his government has arrested dozens of political opponents, journalists, and activists in a vicious campaign that has drawn a wave of fresh sanctions from the United States and European Union.

But while Ortega’s repressive tactics have made headlines, his regime’s role in enabling an environmental disaster with far-reaching consequences for the global climate has received much less attention.

Nicaragua, home to the second-largest rainforest in the Americas after the Amazon, is losing its forests at the fastest rate in the world. Deforestation has surged since 2014, when Ortega took direct control of Nicaragua’s national forestry agency as part of a broad power-grab that cemented his personal control over the impoverished Central American country.

United Nations figures analysed by Our World in Data, a nonprofit initiative directed by academics at Oxford University, show Nicaragua’s average annual forest loss increased from 1.34 percent between 2010-2015 to 2.56 percent from 2015-2020.

This environmental disaster has been fueled by corruption inside Nicaragua’s forestry agency, the Instituto Nacional Forestal (Inafor), and enabled by the first family, according to a cache of leaked documents analyzed by OCCRP.

The Inafor data shows the first lady Rosario Murillo — who is also the vice president — and other public officials intervened directly in the agency’s work, using it to hand out favors to politically connected companies. In another case, the data shows, a U.S.-sanctioned Supreme Court judge appears to have benefitted from an Inafor reforestation program.

OCCRP reporters also conducted dozens of interviews that expose how indigenous communities have been sidelined while outsiders log their forests –– and how basic governance and oversight functions have been subverted to the interests of the ruling family.

Nicaragua’s former environment minister, Jaime Incer Barquero, said illegal land grabbing in indigenous territories — a key driver of deforestation — is happening with the “consent of authorities at every level.”

“Corruption is the principal cause of all of these disgraces,” he said.

A former Inafor official, speaking on condition of anonymity due to security concerns, said the agency would hand out forestry permits at the direction of the presidency for political reasons, or to companies whose true owners are unknown.

“Their function is to make it appear legal, even though it isn't," said the official. "It's not only drugs that have a mafia, but also timber.”

A senior official from Nicaragua’s Ministry of External Relations did not respond to a request for comment. Murillo acknowledged receiving questions from reporters, but did not respond to them.

At a time when preserving rainforests is a key tenet of international efforts to stop climate change, Nicaragua offers a cautionary example of how corruption can subvert attempts to protect the planet. Last year it was the deadliest country in the world per capita for people who defend their land and the environment, according to advocacy group Global Witness.

“Corruption is an important driver of deforestation,” said Paulo Moutinho, a senior scientist and co-founder of IPAM Amazônia, a nonprofit research organization in Brazil that studies Amazon deforestation. “There is a sense of impunity related to environmental crimes.”

Trees and Power

In August 2017, Ortega appointed Shanda Vanegas, from Nicaragua’s southern autonomous region, as co-director of Inafor. Vanegas, reportedly the first Afro-descendant woman to hold the position, was determined to root out corruption in the agency.

Her tenure lasted barely four months.

That December, Vanegas wrote an anguished letter to Vice President Murillo announcing her resignation and denouncing corruption in Inafor, in which she blamed “internal mafias” for blocking her attempts to clean up the agency.

Emails in the cache of leaked documents shows Murillo — whom the U.S. Department of Treasury described as the “de facto co-president of Nicaragua” when it sanctioned her for corruption and human rights abuses in 2018 — kept a tight grip on Inafor, weighing in on everything from official reports to agendas for meetings with international donors.

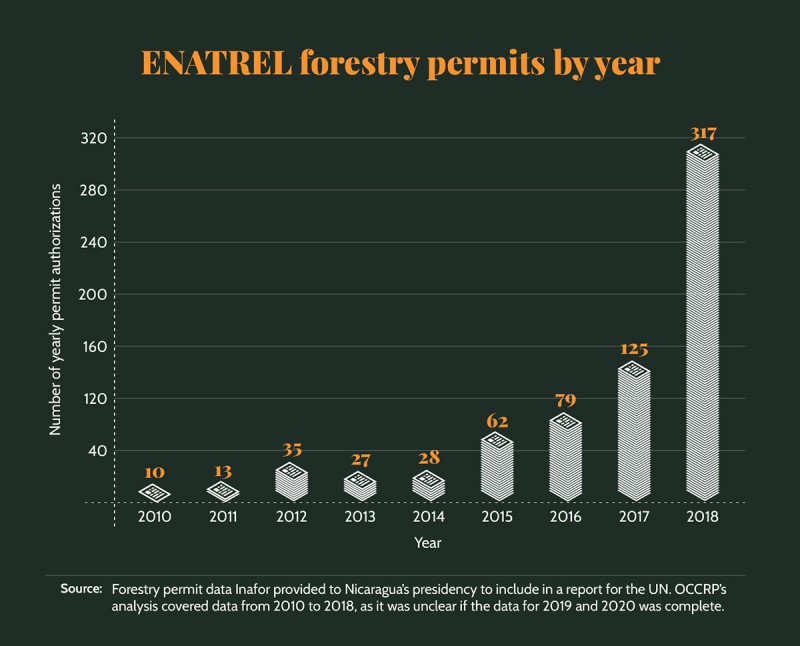

In one instance, Murillo intervened to help the Empresa Nacional de Transmisión Eléctrica (ENATREL), a state company that distributes electricity and is known to have channeled funds to the first family. OCCRP’s analysis of the leaked materials found ENATREL was the top recipient of forestry permits between 2014, when it received 28, and 2018, when it received 317.

In March 2020, Murillo approved a directive allowing the electricity company to receive permits to cut and prune trees directly from Inafor. The next month, Inafor granted ENATREL a special type of forestry permit reserved for projects in the “National and Municipal Interest.” ENATREL was also the only entity in the leaked documents that was exempted from having to pay for the agency’s inspections.

It’s unclear why ENATREL wanted so many forestry permits. Many applications in the leak say they are needed to expand the country’s electricity network. A public government plan also projected ENATREL would need increasing numbers of Inafor permits for “rural electrification.”

But the most common type of permit ENATREL received was for firewood and charcoal — both widely used sources of fuel in Nicaragua. Experts questioned why the state-owned company would need these permits, given that it does not generate electricity, only transmits it.

The former Inafor official said ENATREL was regularly granted permits despite not meeting “the minimum requirements” to obtain them, and estimated that it failed to restore 80 percent of the areas it cleared. Spreadsheets and emails in the leak list dozens of cases in which Inafor found the state company had not restored or repositioned cleared trees, as it was legally obliged to do.

“ENATREL has not shown evidence of having a restoration plan, much less implemented one,” said the former Inafor official. ENATREL did not respond to requests for comment.

Another reason the Ortega regime may have aided ENATREL is that the agency has been used to funnel money to the first family.

In 2018 and 2019, ENATREL paid nearly US$500,000 in advertising contracts to companies led by Ortega and Murillo’s children, according to investigative journalism outlet CONNECTAS. Contracts seen by OCCRP show they included an advertising company controlled by their son Juan Carlos Ortega, which the U.S. sanctioned in 2020 for spreading “regime propaganda.”

Ryan Berg, a senior fellow in the Americas Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said Ortega and Murillo have used their “army” of nine children to ensure the family has control over key sectors of the economy.

“The revolutionary credentials have long faded,” he said. “It's a family business by now.”

ENATREL was not alone in receiving special treatment. Emails in the leak show Murillo also intervened to help a pine resin company part-owned by Osorno Cóleman, a former indigenous commander who battled Ortega’s forces during Nicaragua’s civil war but later changed sides to work with his Sandinista party.

Amaru Ruiz, the director of the Nicaraguan environmental organization Fundación del Río, said Inafor works like an organized crime group, with decisions handed down from above through systems of patronage.

“It functions like a mafia,” he said of the forestry agency. “Everything comes from El Capo and La Capa,” he added, referring to Ortega and Murillo.

‘Totally ILLEGAL’

Not everyone inside Inafor was willing to accept the decisions handed down from the president’s office without question.

Aid Money Diverted?

Despite concerns about Nicaragua’s government driving deforestation, international donors have plowed millions of dollars into environmental projects in the country.

An OCCRP tally found that between 2007, when Ortega began his second term in office, and November 2020, donors including the United Nations, the World Bank, and the Inter-American Development Bank approved over $513 million in grants, co-financing, and loans to Nicaragua. The country was also included in some $3.68 billion of regional and international funding handed out by the Global Environmental Facility, which distributes funds from major international donors.

The funding has drawn criticism from conservationists and indigenous rights groups.

"The Nicaraguan government has demonstrated that it cannot protect our communal lands, our forests, or our indigenous and Afro-descendent population,” the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples and Afro-descendents of Nicaragua wrote in an open letter to the UN’s Green Climate Fund, after it approved the $115 million Bio-CLIMA project in November last year.

The World Bank, which withdrew its backing for the project early this year, citing concerns about implementation, said it “stands ready to continue supporting forest conservation projects in the future”. The Green Climate Fund did not respond to a request for comment.

But data from the Inafor leak shows one of Nicaragua’s key reforestation programs may also have been used to benefit an Ortega ally.

Many of the thousands of emails and documents in the cache of data relate to the agency’s National Reforestation Crusade, when everyone from police and soldiers to students and local volunteers plant trees around the country. The annual crusades have reportedly planted close to 250,000 hectares since they started in 2007.

The crusades are part of the National Forestry Program, which receives funding from the Inafor-managed Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Forestal (FONADEFO). The fund was established in 2006 to support sustainable forestry management projects with a mix of money from the state, private donations, and grants from international donors, which have included the World Bank.

Nicaraguan ecologist Fabio Buitrago said the crusades have been used to benefit Ortega’s allies by funding private plantations over public projects. Under Nicaraguan law, anyone who operates a forest plantation can deduct up to 100 percent of land taxes and 50 percent of municipal taxes on land sales.

"It was a pretext to channel money to individuals and companies who aligned with the government," said Buitrago, from the leading Nicaraguan environmental group Fundación Nicaragüense para el Desarrollo Sostenible (FUNDENIC). "A good part of the money that they were able to raise did not end up being directed to reforestation of public lands."

One beneficiary, the leaked Inafor data shows, was Marvin Ramiro Aguilar Garcia, the vice president of Nicaragua’s Supreme Court and a senior member of the Sandinista party. A close ally of Ortega and Murillo, Aguilar was sanctioned by the U.S. last year for supporting the “regime’s systematic identification, intimidation, and punishment of political opposition."

A spreadsheet detailing plantations registered for the 2018 crusade shows Aguilar operated an Inafor plantation in San Pedro de Lovago, a municipality in the central region of Chontales, where both he and Ortega were born. Others list dozens of tiny parcels of land he owns in Santo Tomas and Juigalpa, also in Chontales, where he also received trees that year and next.

Buitrago said it would be illegal for Aguilar to receive benefits from FONADEFO under the fund’s rules and Nicaragua’s Constitution. Reporters tried for months to find out details of the payments, and other information about Inafor’s inner workings, but sources were too scared to speak, fearing for they and their families’ safety amid the current political crackdown.

Neither Aguilar nor Inafor responded to repeated requests for comment.

All of the trees Aguilar received in San Pedro de Lovago in 2018 came from DESMINIC S.A., one of Nicaragua’s largest mining companies, which at the time was owned by Canada’s B2 Gold, the Inafor spreadsheets show.

Like the judge, DESMINIC operates forestry plantations in Chontales, where it owns a major mine called La Libertad. The project has been criticized for displacing indigenous communities and other smallholders in the area, and local people say it has caused environmental damage, including poisoning water sources and killing native wildlife and fish.

Data in the leak shows Aguilar received trees from DESMINIC in 2018, the year after he reportedly signed an agreement for the mining company to provide funding to a government scheme to improve access to justice for people in Chontales.

DESMINIC said it is committed to preserving and managing the environment in the areas where it operates, that the company respects human rights, and does not promote the displacement of indigenous communities, or any others.

In a statement, the company said its “relationship with the Government of Nicaragua, and its officials, is framed in compliance with national laws” and it requires workers and suppliers to follow a code of conduct. DESMINIC did not address specific questions about its relationship with Aguilar.

Ortega’s ‘Slush Fund’

In March 2019, members of an indigenous community cooperative in Nicaragua’s North Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region wrote to Inafor seeking help.

Their cooperative, Bloque Sipbaa, was having trouble getting permits to log and transport wood from lands that collectively belonged to their communities. The delays had chased away a financial backer and “left us indebted to the investor and without credibility as a cooperative,” the letter said.

Just a few years earlier, wrote Bloque Sipbaa’s representatives, the forests in the area had been cleared by another company without approval from Inafor. That company, however, had high-level political connections.

Alba Forestal, as it was called, was part of a sprawling group of joint ventures set up by late Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez as a conduit to provide aid to his close ally Ortega. In 2019 the U.S. sanctioned the group, named Albanisa, with U.S. National Security Adviser John Bolton describing it as a “slush fund of the corrupt regime of Daniel Ortega.”

Alba Forestal was created with the intention of helping rural communities — most of them indigenous — to benefit from trees felled by Hurricane Felix, which ravaged Nicaragua in 2007.

But a 2020 report by El Confidencial and Armando.info found the project was in fact used to clear healthy trees to reap profits for Albanisa. Between 2009 and 2016, Alba Forestal cut down more than 12.4 million cubic meters of timber across Nicaragua, according to Rodrigo Obregon, a former deputy manager in the group.

“The Alba Forestal project in reality was national deforestation,” Obregon told independent Nicaraguan paper Confidencial.

Another report from Connectas and Nicaraguan outlet Divergentes found that between 2012 and 2016, Alba Forestal made almost $6 million by exploiting land belonging to indigenous communities in northern Nicaragua.

A spreadsheet in the leaked Inafor documents shows Alba Forestal was handed six permits covering two areas in Puerto Cabezas, near where Bloque Sipbaa was based, between 2011 and 2013.

Alba Forestal’s business had a devastating impact on Bloque Sipbaa. Its former manager, Juan Carlos Ocampo, said that Alba Forestal undercut the cooperative’s business model, forcing them to sell raw timber for a fraction of the price of the processed wood it had been selling.

When Alba Forestal opened a road into the forest starting in 2007, land-grabbers poured into the community’s territory, seizing plots of land and cutting down trees, according to Mateo Ocampo, who was Bloque Sipbaa’s president at the time.

“Now practically the entire area of the cooperative is ruined,” said Ocampo.

Nidia Matamoros, a former World Wildlife Fund staffer who worked with the Bloque Sipbaa for years, said that the cooperative’s land is now mostly cattle pastures operated by settlers.

“Ecologically, it’s a crime,” Matamoros said.

‘A Complete Network’

Most deforestation in Nicaragua is not caused by state entities, however, but by private companies, and the illegal land-grabbers that often pave their way.

The government has named agribusiness and cattle ranching as the top drivers of forest loss. Environmentalists say Nicaragua’s booming gold industry is also a growing problem, with mining projects causing deforestation and pollution, and driving violence against indigenous people.

Despite presenting itself as anti-deforestation — Ortega even refused to sign the Paris Agreement for two years on the basis it did not go far enough — Nicaragua’s government has worked hard to promote these sectors. From 2006 to 2017, mining concessions more than tripled as environmental regulations were slashed and the government created a state mining company to cash in, according to Nicaraguan environmental group Centro Humboldt.

State investment agency ProNicaragua has also been criticized for offering vast amounts of land for plantations and seeking to attract foreign agribusiness with the “Most Aggressive Fiscal Incentives in the Region.” ProNicaragua is run by Ortega and Murillo’s son, Laureano Ortega Murillo, who the U.S. sanctioned in 2019 for engaging in “corrupt business deals”.

Mining and agribusiness also encourage land grabbing, where settlers illegally clear land that they later sell to these companies. Buitrago estimated 80 percent of deforestation in Nicaragua is illegal, much of which experts say is enabled by corrupt local officials.

The former Inafor official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said the central government has tried to eliminate authorities in indigenous territories that do not do their bidding. "It’s a complete network, that is why they guarantee control over the elected territorial authorities,” they said.

Incer, the former environment minister, said local government officials also play a critical role in this network of environmental corruption.

“Local authorities in those municipalities and those departments are the ones in charge of giving permits, or turning a blind eye, or submitting to a payment to let the trucks go through,” he said.

“It is a whole skein of corruption that is destroying the survival capacities of Nicaraguans and making Nicaragua a poorer country."