The phone line crackled with static — and tension — as senior executives from Eastern Europe’s largest timber processor discussed a new Romanian law that could spell the end to a business practice that had netted them millions of dollars in free wood.

For over a decade, HS Timber had required its Romanian suppliers to deliver logs that were at least 10 centimeters longer than recorded in official paperwork. The Austrian company was so powerful that many of its suppliers feared they would be frozen out of the Romanian wood industry if they did not comply with its demands for free “overlength.”

While it is common for suppliers to deliver logs with small variations in length, OCCRP’s investigation found HS Timber required its partners to provide extra wood for no extra charge. Contracts, complaints, and internal investigations by Romania’s state forestry agency indicate the practice was widespread, allowing HS Timber to accumulate large amounts of wood that were not officially declared. Over the years, this could have netted the company an estimated 1.6 million cubic meters of timber — the equivalent of cutting down more than 3,700 hectares of forest — worth some $34 million, according to calculations by reporters.

The extra wood was not officially recorded, meaning that authorities could not keep tabs on how many trees were being cut down, or tax HS Timber for processing it. But in a bid to make sure all Romanian timber is traceable, the government proposed a new law this year that would force wood companies to keep more exact records of the size of the logs they sold.

As lawmakers geared up to vote on the legislation, which threatened to curtail HS Timber’s ability to demand free extra wood from its suppliers, company executives jumped on a call.

“I return to the discussion of the lengths of the logs,” HS Timber’s top executive in Romania, Dan Banacu, said on a recording of the March 2022 phone call obtained by reporters, and verified through voice analysis. The authorities “are saying that if we measured the real length of the logs, we would not have these differences.”

“You are correct,” replied one of his subordinates, pointing out that the company’s suppliers would soon “have to switch to the real length of the logs as well.”

This is the first time senior HS Timber executives have been recorded discussing their demands for “overlength.” But it’s far from the first time that the company’s Romanian business has been investigated by authorities for not declaring all the wood it received.

Prosecutors and state forestry officials have conducted at least five probes into HS Timber for requiring free extra wood since 2011, OCCRP has learned. In 2018, the Directorate for Investigating Organized Crime and Terrorism carried out nearly two dozen raids related to corruption in the timber sector, including illegal deforestation, organized crime activities, and failing to declare wood it received. At least seven current and former HS Timber employees were informed they were suspects in the case, according to correspondence obtained by reporters.

Sources close to the ongoing investigation said officials are preparing a case against HS Timber for receiving extra wood without reporting it, which may infringe laws requiring processors to keep records of the origin of all of the timber they process. The sources close to the investigation, as well as forest guards and a financial expert, said it could also constitute tax evasion. Asked for comment, the Directorate for Investigating Organized Crime and Terrorism said it couldn’t provide details on the investigation.

HS Timber Group denied any wrongdoing, saying it complied with national standards and any discussions of lengths with the environment ministry and its staff were conducted transparently, in order to iron out any legal ambiguities.

“We are … the only company in Romania that rejects volumes of wood that exceed the legal tolerance, situations that we report to the relevant authorities” it said in a statement.

Before the introduction of new legislation on measuring logs, HS Timber said the law “did not provide a fair solution for the ‘extra’ wood” and so a “legislative vacuum was created in which unfair sanctions were applied for a legal and correctly followed procedure.” Since the new law was brought in, HS Timber said it has received “no sanction, and the extra wood reported by the receiving company was no longer considered non-originating wood.”

Asked about the probes into HS Timber’s conduct covered by reporters, the company said it had “no information about the DIICOT investigation,” adding that it “has not acquired any standing in this case and has not been indicted.”

Romania’s state forestry agency, Romsilva, said it could not disclose any information from internal investigations or reports. The Environment Ministry didn’t address the findings of this article, but said the new law was needed to bring clarity about how logs should be measured when transported from the logging sites.

OCCRP’s investigation adds to a number of questions about how HS Timber sources its timber in Romania and Ukraine. Thousands protested in 2015 after the Environmental Investigation Agency NGO secretly recorded top HS Timber officials accepting illegally logged timber and local media revealed the company had lobbied Romania’s prime minister against a law that would limit its hold on the timber market. The following year, OCCRP and RISE Romania reported that the company had been sourcing illegally harvested wood from organized crime gangs.

HS Timber publicly pledged to clean up its supply chain in 2017, and last year the company was readmitted to the Forest Stewardship Council certification scheme, which is meant to guarantee the traceability of its wood. But OCCRP has uncovered evidence that one of its mills was under-declaring the length of logs it received from Romania’s state forestry agency as recently as August.

Sources in the timber industry said the undocumented extra wood delivered to HS Timber is turned into biomass, making it virtually impossible to trace where it may have ended up.

These findings raise fresh questions about the sustainability of HS Timber’s global supply chain. Roughly three-quarters of the company’s production is sold in Europe, according to its latest sustainability report, while the rest is exported to countries such as the U.S. and Japan.

Buyers see this as “safe wood compared to other sources” because it comes from Europe, said Alexander von Bismarck, the U.S. executive director at the Environmental Investigation Agency. But, he added, “there are still big loopholes that will allow those companies to take shortcuts.”

‘Everyone Kept their Mouths Shut’

Alin grunted with irritation as he tried to find the words to describe his long history as a supplier to HS Timber. After a long pause, he leaned back in his chair, lit a fresh cigarette, and began to tell his story.

Alin grew up in the countryside and has been working in forestry since he was a teenager. Now a gruff middle-aged woodsman with a strong country drawl, he knows the Romanian timber industry like the back of his hand, and can rattle off information on the different kinds of wood logged from its forests and the various companies, large and small, that buy the timber. He says HS Timber is notorious for its overlength demands.

“The extra lengths were written in the contract — minimum 10 centimeters, maximum 25 — but we were not paid for them,” he said, asking to be referred to by a pseudonym out of concern that his business would suffer if he spoke out against HS.

The extra lengths were written in the contract — minimum 10 centimeters, maximum 25 — but we were not paid for them.

Romanian forester

As proof, he brought out two contracts his logging company signed with the Austrians, in 2010 and 2011. The documents spell out in black and white the 10-25 cm of “overlength” that suppliers must provide. Any logs that are not at least 5 cm longer than their official length will be downgraded by a full meter, and their price will be cut.

In contrast, the delivery papers for the wood that Alin supplied to HS Timber — which are required by law to accurately record how much wood is being logged from a forest — described the logs as exactly 3 or 4 meters long. Comparing the documents for a single transport that Alin made, OCCRP reporters calculated that HS Timber failed to register 44 meters’ worth of wood.

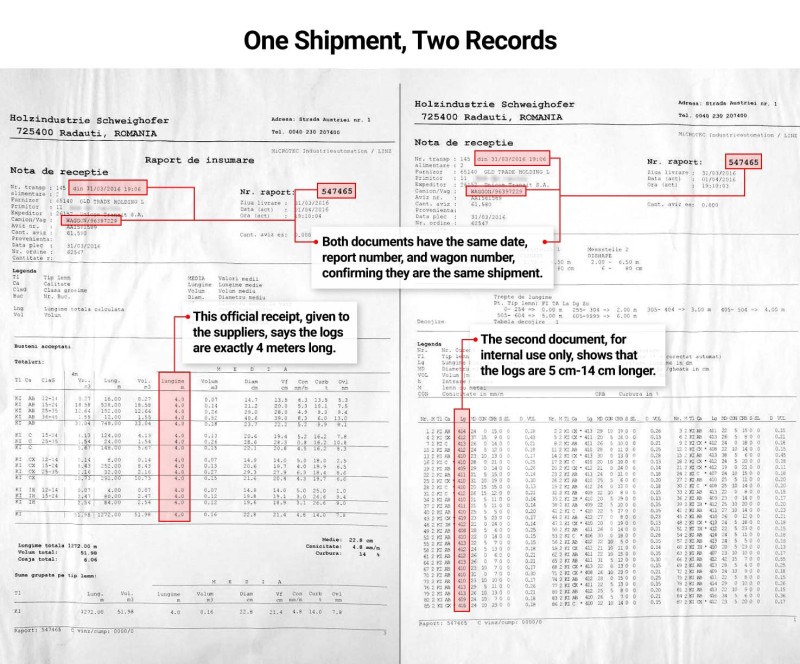

HS Timber used a similar system with other suppliers, including the state forestry agency, Romsilva, according to contracts and internal documents obtained by reporters. In several cases, HS Timber issued two sets of papers for the same shipment. One, given to its suppliers as an official receipt, measured the logs at exactly 4 meters. The other, for internal use only, described them as between 5 and 14 cm longer.

HS Timber said it was transparent with its suppliers about the quality criteria for its deliveries, and denied it had issued conflicting paperwork for the same shipment.

“We give our suppliers, upon request, access to the raw data from the electronic measurement protocol, but this does not replace the receipt note. This can be used for complaints. We rarely receive complaints about the measurements we take,” the company said.

Alin said he didn’t complain because he worried HS Timber would use its stranglehold on the market to squeeze him out of wood auctions, which would make it virtually impossible to sell his timber at all. Last year, the company was fined 10 million euros in Romania for anti-competitive practices. Romania’s Competition Council was found to be exchanging sensitive information with other bigger operators, creating a cartel that allowed a few large companies to get hold of cheap wood.

“Everyone kept their mouths shut and carried on, because of their monopoly. ... Everyone went to them because they didn’t have anywhere else to deliver,” Alin said.

In 2011 — the year Alin signed his second contract with HS Timber — the Austrian company processed almost 2.3 million cubic meters of Romanian wood, reporting profits of $100 million. But as business boomed, Romania’s forests were disappearing.

Using HS Timber’s production figures from 2010 to 2016, OCCRP calculated that the company could have received upwards of 875,000 cubic meters of extra wood from its partners, worth close to $16 million. If the company continued to process the same volumes until August 2022, when it received the most recent complaint about under-declaring, it would have received at least 1.6 million cubic meters, worth an estimated $34 million, since 2010.

How We Came up with the Calculation

To work out how much extra wood HS Timber may have received from its suppliers, OCCRP started with the company’s own production figures.

Based on the average density of trees in Romania’s softwood forests, even a conservative estimate of the extra wood equates to the deforestation of around 3,700 hectares, or around 5,000 soccer fields.

Four sources in the wood industry said HS Timber converts this extra wood into biomass briquettes, a supposedly green source of energy made from renewable materials such as wood, plants, and animals.

“When it is turned into biomass,” Alin said between cigarette puffs, “well, it becomes untraceable.”

HS Timber did not respond to questions from OCCRP on what happened to the extra wood.

Inexplicable Shortfalls

Known as the “lungs of Europe,” Romania is home to the largest remaining natural forests in the EU, but they are disappearing fast. Data from the National Forest Inventory shows some 38 million cubic meters of forest is logged every year, only half of which is legally cut.

In 2015, Romania’s Supreme Council of Defence declared illegal logging a potential national security risk, owing to its impact on both the environment and the national budget. Forestry and furniture making count for around 3.5 percent of Romania’s GDP. The country is now facing an infringement procedure by the European Commission for failing to protect its woodlands, including allowing state-backed logging in protected areas.

HS Timber’s Romanian business was built on processing wood from state forests. After opening its first factory in 2003 in Alba county, in Transylvania, the company signed a multi-year contract with Romsilva giving it access to huge swathes of prime softwood timber, like pine and spruce.

But HS Timber appears to have treated the forestry agency as it did many of its thousands of private Romanian suppliers. An official from Romsilva, who spoke to OCCRP on condition of anonymity for fear of losing their job, said HS Timber also required an “overlength” on the logs it received from the state agency. As with Alin, if the logs were under 5 cm too long, HS Timber would downgrade the amount it paid for them.

“These terms were not included in the original contract, but in the annex,” he said.

Foresters on the ground were not always aware of these terms, however. The source said that at several points, foresters in Alba county, where HS Timber opened its first mill, noticed that around a tenth of the wood on every truck delivered to the company was not being recorded. Concerned that they would be blamed by their bosses for the shortages, in some cases they illegally logged more trees to make up the difference, the source said.

Documents from internal Romsilva probes back up his claims, showing that state forestry employees repeatedly complained that the Austrian company was not paying for all the wood it received from them because the logs didn’t have “overlength.” The issue came to a head in 2011 when a group of Romsilva foresters wrote a series of letters to their managers complaining about the issue.

“We raise this issue because it isn’t a singular occurrence, it is happening with almost every truck that we send to Holzindustrie,” explained one letter from February 2011.

In a response to one of these complaints, seen by OCCRP, HS Timber said it had cut Romsilva’s pay because two dozen 3-meter-long logs that did not have the required 5 centimeters of overlength were downgraded. Another three logs were also downgraded from 4 meters to 3 meters for lacking overlength.

At one point, frustrated that management didn’t seem to be taking their complaints seriously, foresters from Alba county took matters into their own hands. They loaded several trucks with logs, painstakingly recorded the length of each one, and documented it all with photographs. When HS Timber recorded receiving less wood than measured, the foresters thought they had all the evidence needed to hold the company to account.

A complaint was filed with prosecutors from the National Anticorruption Directorate, who interviewed several Romsilva executives. At the same time, Romsilva launched its own internal probe to see if HS Timber was under-counting the amount of wood it received.

But the Romsilva source said the internal control officer who was investigating the case decided to blame the officers who brought the complaint rather than face the wrath of his superiors. “He told [the people who brought the complaint] that their volume estimations in those trucks were not correct,” the official said, adding that the investigation was then dropped.

Romsilva refused to provide OCCRP with the findings of any internal investigations into HS Timber, saying they were “not public information.” HS Timber did not address questions about Romsilva’s investigations when asked to comment. The National Anticorruption Directorate said it ended its investigation after deciding the allegations didn’t fall within its mandate.

The following year, in 2013, another internal Romsilva investigation in the county next to Alba, Cluj, also found shortfalls of wood, and noted that HS Timber had marked good-quality logs delivered by the state agency as low-grade firewood. The county’s forestry police said they had tried again in 2016 to investigate disparities in how much wood was being delivered and how much HS Timber recorded, but the company had refused to provide documents.

Further northeast, in Suceava county, the Forest Guard said they had inspected one of HS Timber’s warehouses in Rădăuți in 2017. Inspectors concluded the company had broken Forest Code laws on ensuring the traceability of its wood, confiscating 1,842 cubic meters and fining the company a little over $1,200.

In 2018, the Forest Guard from Brasov also confiscated what it said was illegal extra wood from HS Timber. The company challenged the decision in court, but lost. The case is now with Romania’s Court of Appeal.

Asked about the Forest Guard seizures, HS Timber said that “deviations may occur … due to differences in the accuracy of the measurement methods used.” The company said it paid its suppliers only for “wood that met our requirements,” and always “notified the Forest Guard of these volume differences.”

HS Timber appeared to still be trying to extract free wood from its suppliers as recently as this year — after the new law requiring companies to record more exact lengths of logs was passed. In August, a Romsilva official from Bacau county, near HS Timber’s newest factory in the town of Reci, wrote to the company complaining it had undercounted a delivery of logs by roughly 10 percent.

Building ‘Mutual Trust’

Since media reports exposed evidence that HS Timber was receiving illegally harvested wood in 2015 and 2016, the company has tried to reform its image.

In its latest sustainability report, HS Timber says it is committed to transparency, including promoting “mutual trust” with partners. Key to its action plan are 3D laser scanners installed in its three Romanian factories to ensure that “volumes of timber in excess of the legally admissible threshold” are excluded from production.

“The system, authorized and periodically verified by the National Metrology Institute, represents the most advanced technology in the field used internationally,” HS Timber told OCCRP.

CCTV footage from inside one of the factories shows logs delivered to HS Timber being measured and photographed, but internal documents seen by reporters show that the scanners were frequently not employed. A list of more than 73,000 wood deliveries to two factories from 2014-17 obtained by OCCRP shows that scanners were not used to measure the logs in around 58,000 of them — more than three quarters of the time.

HS Timber did not answer questions from OCCRP about why the scanner was not used.

Even when it was used, the scanner seems to have done little to stop HS Timber from under-recording deliveries. In the complaint sent in August, the Romsilva official from Bacau county noted that the system had miscounted how many logs had been delivered.

“The number of logs registered by your scanner is smaller than the one we counted manually. This makes us think that the electronic estimations of the volume of wood might be affected by errors,” the official wrote.

Four days later the manager of HS Timber’s new factory in Reci, Adrian Radu, replied, agreeing to use the “volume of wood given in your delivery papers,” and not the one calculated by the scanner.

The issue of measurements became even more fraught this year, when Romania brought in the new legislation requiring all logging companies to record the exact size of the timber they deliver, removing the previous margin for error that HS Timber had exploited.

The change caused consternation among senior executives in HS Timber’s Romanian operations. “This is very sensitive,” one of the company’s officials can be heard saying in the recording from March. “We have to think when we will measure the real lengths ... the supplier will somehow automatically have to switch to real lengths as well, to get closer to the volume.”

Ciprian Musca, president of the Romanian Foresters Association, which represents more than 2,000 logging companies, including some of HS Timber’s partners, said suppliers should stop delivering timber if they are not paid for the full amount.

“Everyone needs to play fair,” he said. “If you ask me to deliver logs with a length of 4 meters and 10 cm, then this is what I have to write in the delivery papers … the real length of the logs.”