Reported by

When her family comes to visit in the summer, lung doctor Maria Brăcaci Gâjiu’s children and grandchildren like to dine outside in their gazebo – if the local pollution allows it.

“We pray, ‘Lord don't let the wind blow,’ because if it does we can’t eat – ash settles everywhere, that’s how thick it gets,” she said.

Brăcaci Gâjiu and her husband live a few kilometers away from one of Romania’s biggest coal-fired power plants, in the southwestern town of Turceni, a place where residents are permitted to retire two years early due to the pollution levels.

The nearby plant is owned by Complexul Energetic Oltenia SA, Romania’s state-owned energy company, which supplies one fifth of the country’s electricity through three major plants. Oltenia almost exclusively burns lignite, a low-grade coal considered the most hazardous and polluting form of fuel.

Lung doctor Brăcaci Gâjiu and her husband with a copy of the court document they filed against Oltenia, requiring the company to reduce ash pollution, a case they won.

Like coal companies across the European Union, Oltenia must buy ‘emissions allowances’ from the bloc that give it the right to produce a certain quantity of carbon dioxide annually. The financial burden of this cap-and-trade system is designed to incentivize firms to transition away from fossil fuels such as lignite, which is associated with higher rates of premature death, childhood asthma, and neurodevelopmental issues, plus the degradation of local water resources.

But Oltenia may be paying considerably less than it should by underdeclaring its carbon dioxide emissions levels, according to an OCCRP data analysis that relies on a UN-recommended approach, which was vetted by industry experts.

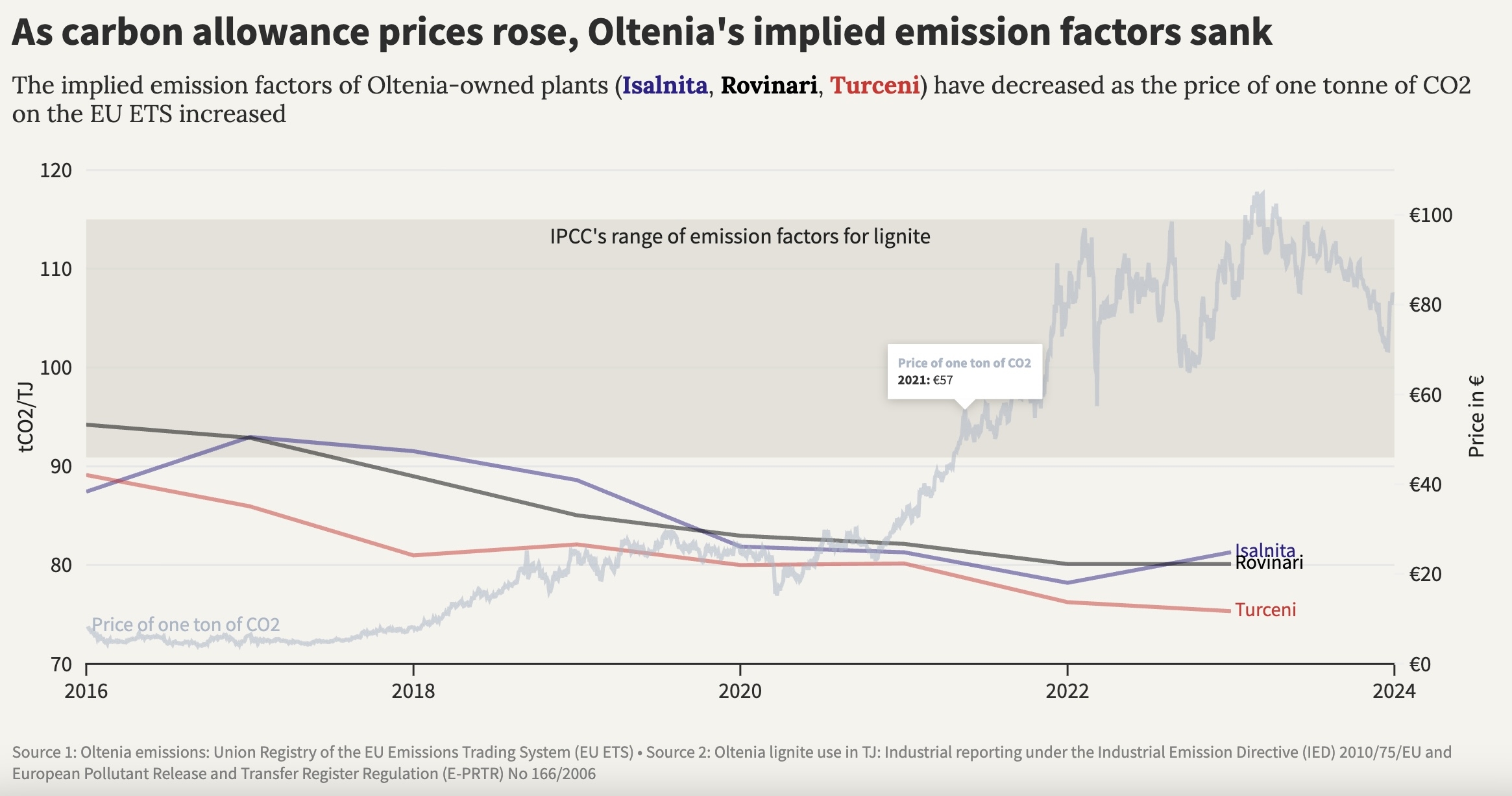

Over the last eight years, Oltenia appears to have calculated its emissions in a way that suggests its lignite plants are unusually low emitters when compared with the national averages of other plants operating in the EU. This has coincided with a steady increase in the cost of EU emissions allowances.

Based on conservative estimates, Oltenia’s possible underreporting of emissions could have saved the firm over 250 million euros in carbon taxes to the EU — money that is meant to be invested in green energy. According to OCCRP’s estimates, the company has paid approximately 2.2 billion euros in carbon allowances during this time.

View of a dust storm near Brăcaci Gâjiu’s home, with an Oltenia lignite plant in the background.

When reached for comment, the state-owned energy company conceded that it had reported lower emissions in the past seven years. Oltenia explained that this was due to the “poor-quality” lignite that the firm extracts from its mines in Romania, which it said has a low energy content and burns inefficiently.

Yet multiple experts who reviewed the analysis described this explanation as unlikely, as low quality fuel would normally generate higher — not lower — emissions to produce the same amount of power. They also cast doubt on Oltenia's claims that the lignite it burns has unusually low combustion rates, a scenario that would also require a plant to burn more fuel to generate the same amount of electricity.

“From my desk in Berlin, I don't believe these figures,” Hauke Hermann, an energy expert and senior scientist at the Öko-Institut in Germany, said of Oltenia’s reported emissions data and its explanations.

“I'd recommend having an independent lab to check them and I'm 99 percent sure that they would find an under-estimation."

Oltenia’s potential skimping on EU carbon taxes comes at the same time that the debt-hit company has been receiving hundreds of millions of euros in aid from Brussels. Under the terms of a deal struck in 2022, Oltenia was supposed to use the money to phase out coal in favor of natural gas and renewable energy sources.

However, Romania Energy Minister Bogdan Ivan said this September that the country could not afford to shutter its coal-fired power plants by the end of the year as had originally been agreed. That means Oltenia will continue burning lignite, and polluting.

Oltenia’s smokestacks power plant burning lignite, in Turceni, Romania.

Sam Van den Plas, policy director at the nonprofit Carbon Market Watch, said the findings raise questions about the validity of Oltenia’s emissions reports and a “potential lack of checks” in the EU’s emissions-trading system, known as the EU ETS.

Any underreporting would not only have saved Oltenia funds, but it would have also undermined the system more broadly, he added, leading to “unfair competition for other power plants” in the bloc.

The state company's emissions reports are checked by an independent verifier before they are submitted to national authorities, who compile countrywide data for the EU. Yet Oltenia owns and operates the laboratory whose analyses form the basis of its reports, making it difficult for outsiders to assess the underlying data.

“The ultimate question here is: 'who verifies the verifier?',” said Van den Plas, urging the European Commission to “take note” and “propose improvements” to the legislation governing the cap-and-trade system.

Brice Böhmer, Transparency International’s Climate and Environment Lead, said Oltenia’s ownership of its laboratory represents a potential “conflict of interest” that highlights how “the whole ETS system has integrity loopholes at its core.”

“The laboratory in charge of measuring emissions should have a degree of independence from the operator,” he said.

When reached for comment, a spokesperson for the European Commission said that while EU law permits power plants to use their own laboratories to analyze emissions, the regulations “strongly prefer the use of external, accredited laboratories,” especially for higher emitters like Oltenia.

When queried, Oltenia said that Romanian authorities did not consider its use of its own lab to be a conflict of interest.

Do you have a tip about integrity issues related to the EU ETS?

'Not Plausible'

To calculate how much carbon dioxide their smokestacks release annually, power plants use what is known as an “emission factor,” which reflects how much of the greenhouse gas is emitted relative to the amount of energy contained in the fuel they burn.

While smaller plants typically use emission factors based on national averages, or a set of “default values” provided by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), large facilities such as those run by Oltenia calculate their own figures for more precision.

Although this data is not publicly available, OCCRP was able to calculate the state energy company’s emission factors by comparing two metrics publicly reported by the company to the EU annually: the energy theoretically contained in all of the lignite burned by each plant over the course of one year, and those plants’ annual carbon dioxide emissions.

By dividing each plant’s emissions with its fuel intake, reporters found what is known as the plant’s “implied emission factor.” The IPCC recommends using this data point to verify and compare emissions data across different countries.

OCCRP’s analysis revealed that the firm’s implied emission factors were far below the national averages of lignite plants in other EU states. That would suggest Oltenia’s plants were unusually low carbon dioxide emitters, meaning they could purchase fewer allowances for their annual output.

Most of the plants’ implied emission factors also fell outside the range of “default values” for lignite calculated by the IPCC.

For instance, Oltenia’s lowest implied emission factor in the past eight years — which was reported by one of its plants in 2023 — was 18 percent below what the IPCC considers to be the bottom range for lignite.

When reached for comment, Oltenia said it had been using higher emission factors than those calculated by OCCRP and that OCCRP’s calculations “may contain an error.” The company later said the methodology used by OCCRP was not applicable because its lignite plants employed cogeneration — a specialized process that allows power plants to generate both electricity and heat at the same time.

But Oltenia did not provide any details or evidence of these claims, and the plants examined by OCCRP are not listed by Romania's national energy regulatory agency as having accredited cogeneration units. Furthermore, two experts confirmed that cogeneration would not affect the manner in which OCCRP calculated the firm's implied emission factors.

Oltenia acknowledged in its response to reporters’ questions that its emission factors had decreased over the past seven years. This was due to Romania’s low-quality lignite, the company said.

View of lignite at Oltenia’s facility in Turceni, Romania.

Emissions experts consulted by OCCRP, and who reviewed reporters’ methodology and Oltenia's reply, cast doubt on this explanation.

“Justifying low emissions through poor coal quality is questionable, because low-grade lignite should normally produce more emissions per unit of energy produced, not less,” said Mihai Constantin, a senior researcher at EPG, a non-profit think tank focused on energy and climate policy in Romania.

Hermann, the German energy expert and senior scientist, concurred.

“Lignite is a bad fuel: there is a lot of ash and water in it, so you need to transport and burn a much larger quantity than other types of coal to produce the same amount of energy, which is very inefficient and leads to higher carbon dioxide emissions," he said.

According to Euracoal, an umbrella organization for Europe’s coal industry, there have been no changes in the composition of Romanian lignite between 2015 and 2022.

Questions Over Oxidation Factors

Oltenia did not always report such low emissions data.

An independent study published by Babeș Bolyai University notes the company’s emission factors were much higher in 2010, and in line with values used by other countries, when the cost of an EU carbon allowance was just 14 euros per tonne of carbon dioxide.

According to OCCRP’s estimates, the implied emission factors used by the company’s Rovinari and Turceni plants later decreased by approximately 15 percent between 2016 and 2023. During the same period, the price of carbon allowances increased to almost 90 euros per tonne.

If over the past eight years Oltenia had instead used the lowest default emission factor provided by the IPCC, it would have had to pay at least 250 million more euros in carbon taxes, OCCRP estimated. Companies also have to pay a 100 euro penalty for every unreported tonne of emissions.

OCCRP is not the first to question Romania over the unusually low emissions reporting in its lignite sector, which is dominated by Oltenia, whose plants account for 99 percent of the country’s production.

In 2016 and 2018, UN observers asked the country to explain its low average national lignite emission factors, which closely match the figures OCCRP estimated for Oltenia.

Several years later in 2022, the observers again asked Romania to explain why its emission factors for lignite were so far below the IPCC’s default ranges.

In response, Romania, like Oltenia, cited the country’s poor quality fuel, which it said burns inefficiently for a variety of reasons, including old equipment.

The experts involved in overseeing the UN reports, which labeled the issue as "Resolved" after receiving a response, told OCCRP they were not authorized to comment.

Drone image of an ash pit at Oltenia's Turceni plant

‘Lack of Checks’

Reporters were unable to identify a specific regulatory body or agency that is responsible for further scrutinizing data submitted under the EU ETS and following up on questionable submissions.

The European Commission spokesperson told OCCRP it was the duty of national authorities to “investigate and, if necessary, impose corrective measures or penalties” in cases of misreporting.

“This duty includes following up on verifier reports, conducting their own checks, and taking action against non-compliant operators,” the spokesperson said.

When reached for comment Romania’s National Environmental Protection Agency, which collects the data from operators and produces Romania’s annual emissions reports, said it played no role in the audits of each company’s emissions reports that are carried out by private verifiers.

It also refused to share Oltenia’s figures with reporters, claiming that doing so would entail “a lot of work both physically and mentally,” and would require the operators' permission. It did not respond to specific questions about Oltenia’s reports.

The independent verifier who has been checking Oltenia’s emissions reports since 2018 told OCCRP it “analyzes the accuracy and completeness” of the company’s yearly submissions, including checking for the “correct application of emission factors.” It does not, however, "have the capacity to perform laboratory analyses” or "request other laboratory analyses in addition to those provided,” the company said.

Oltenia said Romania’s national agency did not carry out any inspections at its plants “because there were no grounds to do so.”

‘Total Indifference’

The goal of Europe’s emissions-trading system is to make releasing carbon dioxide so expensive that companies are driven to invest in greener energy sources.

“That’s why coal plants are shutting down across Europe, even in countries without ambitious climate policies: the economics simply don’t stack up,” said Alexandru Mustață, a Romanian campaigner for the NGO Beyond Fossil Fuels.

EU Emissions Controversies

Yet as Oltenia has potentially been paying less tax than it should, the Romanian government has also been dragging its feet on transitioning away from coal-fired power plants, citing energy security concerns and delays in investments to alternative energy sources.

“Romania could fall into energy poverty or even blackout if these power plants are shut down, especially during the winter period, when we have neither solar nor wind energy, and this could lead to Romania being paralyzed,” the country’s Energy Minister has warned.

Corina Murafa, a former energy expert for the World Bank, suggested Romania’s failure to move away from coal was a “political decision”, and could be related to a desire to keep receiving EU subsidies.

“The problem is [the subsidies] are being granted during the implementation period of this restructuring plan [for transitioning away from coal]... With this restructuring plan constantly being extended and renegotiated, theoretically, they’re also seeking to extend the subsidies,” she said.

While Romania’s government says that moving to alternative energy sources is expensive, the healthcare costs of dirty air also run high.

Between 2012-2021, pollution from power plants and other forms of industry have cost the EU more than 2.7 trillion euros in the form of negative impacts on health and the environment, according to the bloc’s environmental agency. Data from the same agency shows that in 2021 alone, Oltenia’s plants generated more than 1.4 billion euros in such societal costs.

Lignite ash storm near Oltenia ash pit, in Turceni, Romania.

Gheorghe Sanda, the head of Romania’s national environmental guard in Gorj county, where two Oltenia plants are based, said his staff make routine inspections to ensure the coal plants are following regulations — and find frequent violations. In the past decade, they have fined the two Oltentia plants more than 30 times for infringements such as exceeding air pollution levels or illegally depositing waste.

“We can't demand perfectly clean air — but we do expect demonstrable efforts to show us they are doing everything within their power to address the problem,” said Sanda.

Oltenia told OCCRP that it had implemented measures demanded by the national environmental guard in a timely fashion.

Brăcaci Gâjiu, the lung doctor, fears for the health of her community, and has found the response from authorities to be dispiriting.

“I can tell you, I’m deeply disturbed by their indifference,” she said. “Total indifference.”

This investigation was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe and Arena for Journalism in Europe.