For centuries people have searched for gold buried in the Atrato river basin in Chocó, one of the most unique and biodiverse places in the world, nestled deep in the verdant jungles of northwest Colombia.

But traditional artisanal mining has been dying out since foreigners arrived two decades ago. The bowl-like “batea” long used to pan for precious metals has been replaced by huge dredgers, known as “dragons,” that suck out vast quantities of soil from the rivers’ banks and floor.

Before, “we would carefully search for gold grains to buy food," Jaime, a local miner, told reporters from Cuestión Pública outside his wooden house late last year. “Those machines used up everything. You go out looking for [gold] and find nothing."

Chocó’s rainforests are home to a plethora of rare flora and fauna, including several endangered species and birds not found anywhere else on the planet. The region is also known for its Afro-Colombian heritage. But today, much of it is controlled by guerillas and criminal groups that feed off the illegal mining industry.

Diggers and dragons have reshaped Chocó’s landscape, diverting many of the rivers that snake through the jungle. Mercury, which miners use to separate gold from the sediment, has polluted the region’s rivers, killing dozens of children and leaving many local people with agonizing health problems.

Jaime, whose last name OCCRP is omitting for his safety, said he was forced to seek treatment for mercury poisoning in Medellín and the capital, Bogotá. “I was going to die,” he said. “I had heart problems, brain problems, my whole body hurt, my legs seized up from the pain.”

As Chocó suffers, it’s not always clear who is profiting.

OCCRP and its partners tracked down a number of people, including two U.S. citizens — a chiropractor and a real estate agent — who are being investigated for their role in an illegal mining operation in the region that officials say caused vast environmental damage. Reporters found the two men thousands of kilometers away, in the wealthy suburbs of Miami.

The two Iranian-Americans categorically deny their involvement in any illegal activity. But their former associates and an ex-employee tell a very different story about who benefited from the mining operation that wrought the environmental destruction.

Behind the dispute is an intricate and sometimes bizarre game of alleged betrayal, finger-pointing, and intimidation. While a few of the men associated with the mining have been convicted, others, including the Americans, have not and the Colombian district prosecutor’s office says the investigation is still open.

Court documents filed by Colombian prosecutors in 2018 say the Americans, Hassan Jalali-Bidgoli and Amir Mohit-Kermani, started mining activities in 2011, when they set up two companies to extract and trade gold. The documents show the Bucaramanga district prosecutor’s office issued warrants in December 2018 for the arrest of the two Americans and 11 other people — five of whom have since been convicted of environmental crimes related to the mining operation.

But the investigation into Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani appears to have stalled since then. The prosecutor’s office told reporters that the men are still part of an ongoing probe, but neither of them has been charged and it’s unclear if the Colombian warrants are still active.

Both Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani were found in Miami, where they own businesses and property. Records show the two men, along with Jalali-Bidgoli’s wife, own properties in Florida together worth more than $30 million, although there is no evidence that any of them were bought with money made from mining in Colombia.

Juan José Salazar, a lawyer for the two men in Colombia, disputed evidence of the warrants provided by reporters, writing in an email that "there has never been, nor is there currently in Colombia an arrest warrant against my clients."

“My clients have been in the U.S., in plain sight,” added their American lawyer, David Nuñez. He said they had provided the Colombian Attorney General with “materials that establish their innocence with relation to any illegal mining activities." Nuñez and a Colombian lawyer for the two promised to provide evidence of their innocence, but neither shared those materials.

Several sources, including lawyers for the men, acknowledged that an Interpol blue notice was issued to locate them, though the international police body itself declined to comment, saying the information was “confidential.”

Environmental Destruction

The Colombian court records say Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani became involved in mining in Chocó just under a decade ago.

OCCRP and its Colombian partner Cuestión Pública requested court files about the Americans, but prosecutors refused to release them because the investigation is ongoing. However, documents from the court cases against the five men who were convicted of environmental crimes suggest Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani worked with them, forming a group of companies that mined and traded gold.

In 2011, Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani set up two companies: Talbras SAS, to extract precious metals, and Comercializadora Internacional CI Tala Internacional Trading SAS, to sell them. Talbras’ paperwork says it would sell gold locally, although Comercializadora Internacional’s stated business purpose — to “market Colombian products abroad” — suggests the gold may have been destined for export.

The court records say Talbras initially received approval to mine from the Paimadó Community Council in Chocó, which manages the lands on behalf of local Afro-Colombian communities. However, a senior official at the regional mining agency, Codechocó, said the approval was illegitimate, as the Council did not have the environmental license necessary to allow mining.

At any rate, the Paimadó Community Council later withdrew its approval and Talbras was dissolved as a result in 2013, according to company records.

A point of contention between the various parties is who was involved in the illegal mining operations. Reporters found four court cases related to the illegal mining, though three of them are still under investigation so prosecutors would not provide documents. The fourth case involved the conviction of five people for environmental crimes, and the case file includes indictments, evidence from prosecutors, warrants for arrest, judgments — and information on other people who may appear in the still sealed cases.

The public case refers to a “criminal organization” that carried out mining operations, subsequently called “the organization.” The case files say this organization was initiated when Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani set up Talbras and Comercializadora Internacional. Other companies were added over the course of several years, but prosecutors considered them part of the same organization.

For example, the case file says that in April 2013, the organization added another company named Vencol Mineral SAS, and soon set to work using heavy diggers and dredgers in Chocó’s Río Quito. Lawyers for Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani said they were not involved in Vencol Mineral, and had no knowledge the group was involved in illegal mining.

While who controlled the organization is in dispute, the damage it caused is not.

The first image, from 2011, shows the jungle before Vencol Mineral started operating on the Río Quito. The other, from 2018, shows the destruction their dredges wrought on the river.

In June 2013 and again the following year, Codechocó sent an environmental engineer to assess the impact of Vencol Mineral’s operations. The engineer, Erbin Rodrigo Velásquez Mosquera, told Cuestión Pública that the company had wreaked environmental destruction that would take “thousands of years” to recover from.

“We arrived by boat and the first impact we saw was that they had diverted the watercourse,” he said. “It was no longer the natural course of the river, they redirected it ... They dried it up [and] they flooded it at their convenience.”

The trees that lined the river’s banks had been cut down and replaced by piles of soil carved out from the riverbed, he said. The water, once “crystal clear,” was stained with oil from the dredgers.

Another person close to the case, who declined to be named because they are not permitted to discuss it publicly, confirmed that the mining wreaked devastation in Rio Quito. “Apart from diverting it, they contaminated it in a brutal way with the extraordinary amount of mercury that they put into the river,” said the source, adding that “there are ecological niches that will not be recovered.”

Codechocó later fined the legal representative of Vencol Mineral more than 427 million pesos (about $146,000) over the environmental damage. To date, the fine still hasn't been paid, according to Codechocó.

Then in 2015, the organization moved its operation south to the township of San Miguel to avoid a clampdown on illegal mining in the area where they had been operating, court documents say.

In July 2015, the court records say, the group set up another company called Dragados Asociados San Miguel SAS, which at the time was owned by Jalali-Bidgoli’s mother-in-law’s cousin, Moisés Ortiz Martinez.

Ortiz Martinez was later convicted of conspiracy and environmental crimes and sentenced to four years in prison and a fine of nearly 12 billion pesos ($3.5 million), which was commuted to a suspended sentence. A lawyer for Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani acknowledged the relationship, but said they had no knowledge of Ortiz Martinez’ illegal activities.

Legal Challenges

The environmental damage inflicted by illegal mining in Chocó is so devastating it has made its way to the top of Colombia’s legal system.

By 2017, the court documents allege, the criminal organization had created an end-to-end mining business that extracted gold and platinum in the rainforest and sold it abroad. According to both Codechocó and Colombia’s National Environmental Licensing Authority, none of the group’s companies was licensed to mine precious metals.

Nuñez, the American lawyer representing Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani, denied his clients ever extracted or exported gold from Colombia. Records from a commercial import/export database showed no mention of Comercializadora Internacional CI Tala Internacional Trading SAS, the export company named in the court documents.

Things began to turn sour for the organization in June 2017, when national police, military forces, and Codechocó discovered three of its dredges in the San Juan River.

In December 2018, warrants were issued for 13 people associated with the alleged illegal mining operation, including the two Americans. Five of them were captured that month and convicted of various environmental crimes the following year, including contaminating the environment and illicit exploitation of mining deposits and other minerals.

The defendants’ attorneys, Harlan Lozano Quinto and Cristino Parra Mosquera, told OCCRP they would only answer questions in person at their offices in Chocó. Journalists couldn't meet them there for security reasons.

Gold Rush

Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani declined to be interviewed directly, but said through their American lawyer that they had been inadvertently drawn into the affair when a well-intentioned loan turned bad.

By their account, the saga began in 2010, when the pair lent money to Juan Carlos Marulanda, a Colombian man Jalali-Bigdoli had worked with in South Florida. The money was meant to buy gold in Colombia to sell in the U.S., but Marulanda instead spent it on mining equipment, which he then gave to Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani to pay off his debt.

In a bid to recoup their losses, they then set up the Colombian gold companies, according to their lawyer, Nuñez. He admitted his clients had lent their mining equipment to Ortiz Martinez, but argued they had no idea he was going to use it for illegal mining.

“They had no knowledge of Mr. Ortiz’s use of their equipment for any unauthorized/illegal gold mining activity,” Nuñez told reporters.

Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani’s former business associates told very different stories, however, accusing the Americans of betraying them and sending people to intimidate them into turning over their business.

A former legal adviser to Talbras, lawyer Ángela Salazar Ríos, said she told Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani their gold mining operations were illegal.

“I explained to them, ‘this is not like in any country, here things are already regulated, this is a crime, you have committed many crimes,’” she told reporters.

Nuñez said Salazar Ríos was fired from Talbras after Ortiz Martinez accused her of stealing, adding: “Ms. Salazar’s account is entirely inaccurate. None of it is true.”

Salazar Ríos said she was owed back pay, and filed a suit alleging labor violations, which was dismissed under what she considered “strange” circumstances.

Marulanda also disputed Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani’s version of events, saying the money they supposedly lent him was actually a $100,000 investment intended to expand the mining operations of one of his partners in the region. That partner, Josecarlo Souffront Mozzicato, separately backed up Marulanda’s account.

Souffront said he was later pressured to “transfer” his operations to the two Americans in exchange for about 50 million pesos (around $28,4000 at the time). Fearful, he said he left Colombia in September 2011, after filing a legal complaint, but received a notice the case was closed two years later.

A former associate of Souffront, speaking on condition of anonymity, independently supported his account of being forced into a negotiation and stripped of his business.

Armed Groups in Control

Marulanda also said he fled Colombia late in 2011, after enforcers visited him demanding money.

The pair’s lawyer, Nuñez, said his clients had not hired “anyone to collect on the loan debt” and “deny any allegation that they were in any way involved in criminal activity.”

None of the parties provided documents to back up their various accounts. Corporate filings show Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani opened a Florida-registered company with Marulanda in 2010 and another Colombian mineral trading company with Souffront in March 2011, but it otherwise has not been possible to verify either version of events.

Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani said through their lawyers they have not been in Colombia for years. Mohit-Kermani has been licensed as a chiropractor in Miami, and Jalali-Bidgoli is an architectural engineer and general contractor.

The two men appear to be living well.

Records show Jalali-Bidgoli and his wife have amassed a portfolio of 12 properties worth more than $22 million, including beachfront pads and mansions in exclusive areas. At least three of them were bought between 2013 and 2016, when the organization was operating in Chocó. Mohit-Kermani owns two Miami properties worth $9.7 million, according to documents seen by reporters.

Corporate records show Jalali-Bidgoli is also tied to a network of at least 43 companies in Florida, as well as others in tax havens such as Panama.

Reporters found no evidence Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani’s properties were bought with funds from illegal mining, and their lawyer said they have never made any profit from Colombian gold.

Few Environmental Prosecutions

Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani are still the subjects of an ongoing investigation into allegations of damage to natural resources, environmental contamination, illicit exploitation of gold deposits and conspiracy to commit a crime, according to Colombian authorities.

Five of their alleged accomplices were convicted of multiple environmental crimes in August 2019 and sentenced to four years in jail and each fined close to 12 billion pesos (about $3.5 million). But their sentences were later suspended for three years.

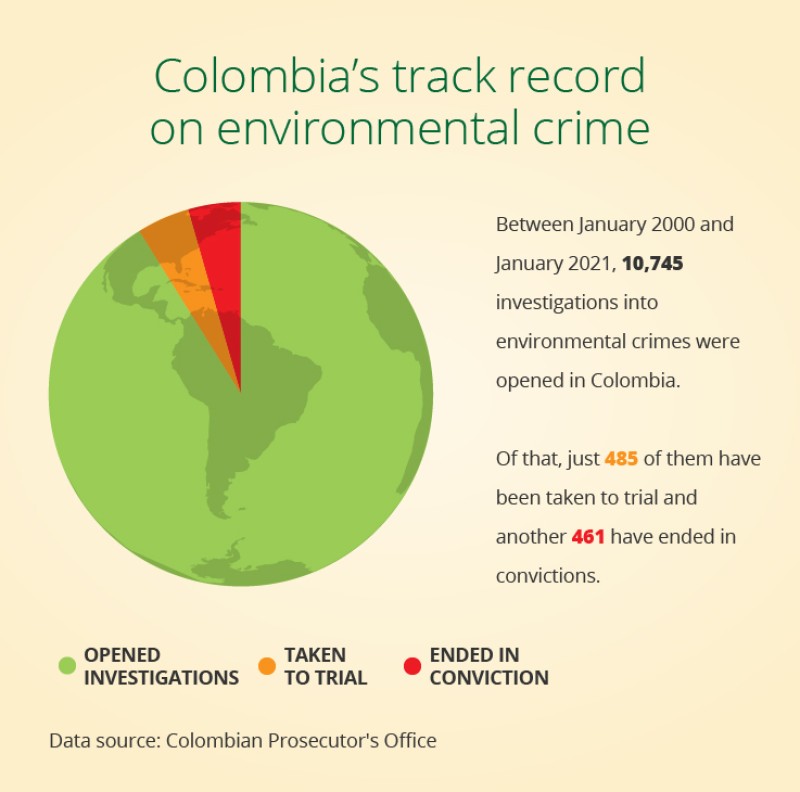

Yet this is still further than most environmental cases get in Colombia. Data from the prosecutor's office shows that out of more than 10,700 investigations into crimes against the environment and natural resources registered between January 2000 and February 2021, only 461 have ended in conviction.

Former prosecutor Jorge Perdomo said the low rate of convictions for environmental crimes was partly because prosecutors lack the skills and equipment to investigate them, and partly because criminal groups control many of the illegal mining areas.

"The crimes associated with illegal mining require special knowledge and instruments, which makes them more complex to investigate."

Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani have also been represented by the law firm of high-profile lawyer Diego Cadena, who is known for having defended several Colombian drug traffickers extradited to the U.S. He is currently under house arrest over charges he allegedly bribed witnesses on behalf of former President Álvaro Uribe, in a case involving ex-paramilitaries who had made damaging claims about the politician.

In August 2020, the illegal mining story in Chocó resurfaced in Colombian media when police reported a confidential informant had provided prosecutors with information about two Iranians that could advance the case. Then director of the Carabineros Police, General Herman Alejandro Bustamante, told Colombian newspaper El Tiempo that their challenge was to “achieve the capture of these two foreigners for the damage caused in Chocó.” Bustamante’s former office confirmed the quote to OCCRP reporters.

However, the press office at the Prosecutor’s Office told reporters the proceedings against Jalali-Bidgoli and Mohit-Kermani are at the “investigation stage” and they couldn't provide more information.