Reported by

Ten years ago Dragana Pećo, a journalist from OCCRP’s Serbian member center KRIK, found herself poring over records in Belgrade’s business registry office. She had become curious about whether there were any companies connected to the city’s newly appointed mayor, Siniša Mali, or his family members.

She had no idea what she would find — but her search turned up so many companies that she ended up having to return to the registry office multiple times to pull all the records. By the time she was done, an exasperated clerk joked: “Does his dog have a company?”

That reporting led to the Mayor’s Story, a series of investigations into the politician’s secretive business dealings and hidden ownership of 24 apartments on Bulgaria’s coast. It was just the beginning for Pećo and her colleagues. Over the next decade, KRIK and OCCRP would publish several more exposes on Mali’s unexplained wealth, including our latest collaboration, which looks at how he paid for private schooling for his children that cost five times his official salary.

While Mali is a prominent politician in Serbia, he is just one of many. So why has he been the subject of so many investigations? Because his story captures the crux of Serbia’s corruption problem and one of the driving forces behind the country’s current wave of protests: the impunity enjoyed by political elites.

KRIK and OCCRP’s reporting on Mali has captured public attention and even triggered official probes over the years. But despite the revelations, his political rise has continued. In 2018 the former mayor became finance minister, a post he has been reappointed to twice more in the years since.

“He represents that no matter how many stories you publish, still institutions aren’t going to investigate,” says Milica Vojinović, the KRIK journalist behind the most recent investigation.

His status can be measured by his proximity to President Aleksandar Vučić, the strongman around whom Serbian power revolves.

“A lot of ministers have lost their jobs, but he’s still a minister and Vučić still has a lot of trust in him,” says Vojinović. “They always go to events together, they hang out privately.”

A photograph posted to Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić's official Instagram page shows Vučić (left) strolling along the Belgrade waterfront with Finance Minister Siniša Mali (right).

As Mali’s political career has flourished, ordinary Serbians have watched their democratic rights erode over the past decade under Vučić’s increasingly authoritarian grip. Since 2016, the country’s ranking on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index has been in steady decline.

In November 2024, the collapse of a newly renovated train station canopy in the city of Novi Sad that killed 16 people became a potent symbol of corruption’s deadly price. Grief quickly curdled into anger, with protesters taking to the streets to accuse authorities of negligence and a lack of transparency around the site’s renovation.

Now, more than six months into the protest movement — the largest to rock Serbia in years — the demonstrators are still demanding accountability for the deaths and are calling for new elections to replace a government they say is too poisoned by corruption to carry out its duties independently.

The protesters are “fighting against this corrupted system they have been reading about for years,” said Pećo, who now works for OCCRP. “They are aware how corruption affects their daily life, how people lose their lives because of the corruption. They don't want to give up until they replace characters like Mali being those who make decisions.”

Serbian students and citizens gather in Belgrade’s Slavija Square to protest government corruption following the Novi Sad railway station accident.

The Apartment Affair

Young, well-educated, but not well-known, Mali first entered public service in the early 2000s as an official in Serbia’s newly formed privatization agency, which was in charge of selling off the former communist country’s biggest companies.

Hailed as a rising star, he would go on in 2012 to serve as an economic adviser to Vučić, who at the time was First Deputy Prime Minister with his newly-victorious Serbian Progressive Party (SNS). The duo, it turns out, had familial connections: according to an interview Mali gave to Croatian press, his brother and Vučić’s brother were “best friends.”

Two years later, Mali was elected mayor of Belgrade, launching him into the public eye.

It was then that KRIK, a scrappy investigative newsroom with only five reporters at the time, began looking into the politician’s background, wealth, and business connections.

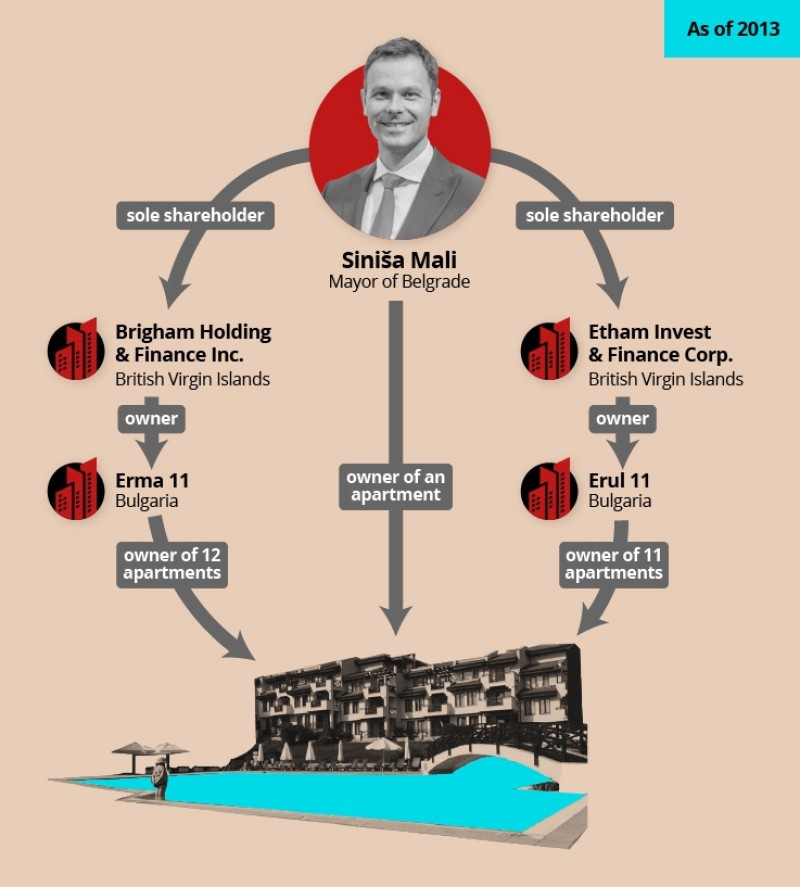

In 2015 reporters published their first series of investigations, with the headline finding that Mali was the director of two offshore companies based in the British Virgin Islands that owned around $6.1 million of real estate on the coast of Bulgaria. His official salary, meanwhile, was the equivalent of around $1,000 a month.

After the story was published, Mali called a press conference to denounce the reporters — and threw in an extraordinary offer.

“If you determine that I am the owner of any of these apartments, they are all yours,” he said. “You will get the key that very moment.”

In 2021, reporters did obtain definitive proof. During their initial reporting, it had only been possible to identify Mali as the director of the British Virgin Islands companies that owned the apartments. The company’s owners were hidden behind the island’s opaque reporting requirements. Six years later, however, files from the Pandora Papers — a set of millions of documents from offshore corporate service providers leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists — revealed Mali to be their sole shareholder as well.

Mali never responded to this finding — and the journalists have not yet received their keys.

A graphic from the 2021 Pandora Papers investigation into Mali's properties.

Multiplying Bank Accounts

During Mali’s mayoral term, KRIK unearthed several more examples of the politician’s lavish lifestyle, which seemed out of sync with a public servant’s salary, including his control over more than 40 bank accounts, into some of which he had deposited large sums of cash. In 2018, a reporter spotted Mali on a business class flight to Rome and calculated that the weekend holiday with his family had cost at least seven times his monthly salary.

As journalists on the corruption beat, Mali’s name was simply hard to avoid, says Pećo. “It’s not like we were only focused on him, but we couldn’t avoid him popping up in other projects that we were investigating.”

One of the most notorious incidents of Mali’s mayoral term took place in the middle of the night in April 2016. Under the cover of darkness, several dozen masked men armed with baseball bats and bulldozers descended on a riverside neighborhood in Belgrade and demolished buildings that had been standing in the way of a government-backed development project Mali was championing.

A restaurant in ruins after the demolition on the Belgrade waterfront in April 2016.

Known as Belgrade Waterfront, the controversial multi-million-dollar project to revamp a stretch of the Sava riverside was funded by the Serbian government and a company from the United Arab Emirates.

The brazen destruction of private property shocked the public and sparked protests. In the aftermath, Vučić — Serbia’s prime minister at the time — said “authorities” in Belgrade’s government were responsible, but never revealed any names. Mali denied that any city institution had been involved.

Nearly a year later, KRIK published a bombshell interview in which Mali’s ex-wife Marija said her husband had bragged about organizing the violent clearance of the neighborhood.

“I had a problem, some people refused to move out. I organized a cleaning operation. People came in the middle of the night and trashed a little bit over there,” Mali allegedly said, according to his ex-wife. “I organized everything myself.”

Vučić later said in a TV interview that though he had no intention of removing Mali as mayor, “an atmosphere has been created where you have to pay that kind of political price.” In April 2017, Mali said he would not run for another term as mayor.

Falling Upwards

But in May 2018, Mali fell upwards. Yes, he was no longer Mayor of Belgrade — he was now Serbia’s Minister of Finance. That means he now held the reins of the Administration for the Prevention of Money Laundering, an agency that had previously investigated him.

After KRIK's reporting on Mali's Bulgarian apartments, Serbia's Anti-Corruption Agency had launched a probe and asked the anti-money laundering unit to check his bank accounts. In 2016, the agency filed a report to prosecutors describing multiple suspicious transactions, including Mali's handling of money well in excess of his official salary, and his failure to fully declare his assets. But Serbia’s Higher Public Prosecutor’s office declined to pursue a case, saying that they saw no evidence of criminal activity.

Aside from one police officer, no one was ever held accountable for the demolition of the waterfront neighborhood, either.

While the official investigations against Mali have dried up, the reporting hasn’t. In 2019, KRIK discovered that Mali’s brother Predrag had been driving an Audi owned by two Serbian businessmen whose companies received lucrative state contracts — including construction of the Belgrade Waterfront project. (The story generated so much interest that KRIK produced t-shirts featuring the Audi logo and the construction site as gifts for readers who donated to them.)

And KRIK’s latest story revealed Mali to be the owner of one of three offshore companies that have paid some $300,000 in private school fees for his children — expenses he previously said in court were covered by his “friends” from abroad.

While Mali once responded to the reporting with denials, he apparently no longer finds it necessary.

“It’s very frustrating when you’re revealing corruption and crime, you’re revealing what … politicians are spending taxpayers’ money on, and they’re in the same position, they’re even being promoted after this,” says Pećo.

“Institutions Don’t Work”

According to Dušan Spasojević, an associate professor at the University of Belgrade’s Faculty of Political Science, Serbia’s culture of impunity is rooted in the ruling SNS party’s “dominance” over “all the institutions…over the media and civil society, but above all in relation to the judiciary.”

The politicians “feel quite comfortable in their positions,” he added. “Maybe they know that one day they will leave power, but they also assume that they will never go to prison.”

The party is now facing one of its biggest tests yet, with the protests uniting diverse segments of the population. Though the movement has been driven by students, support cuts across society. A February poll found that 24 percent of Serbians said corruption was the biggest problem facing the country.

President Aleksandar Vučić at a press conference at the Serbian Progressive Party SNS headquarters in Belgrade, Serbia, on April 3, 2022.

“The whole system relies on corruption,” said Filip Balunović, a researcher of social movements at University of Belgrade. “One of the main systemic illnesses of the state is the fact that institutions don't work. People who hold significant places in the state refuse to simply respond, react, or address the issues of concern.”

The SNS party first came to power in a coalition government in 2012 with a promise to crack down on graft. Vučić was the face of the campaign in global media, and vowed to lead the country forward on its path to joining the European Union.

But “everything changed” after 2014, when a SNS victory in a snap election allowed them to govern alone, says Miloš Resimić, researcher and consultant for Transparency International’s Anti-Corruption Helpdesk. “They started to co-opt judges. The atmosphere among prosecutors became hierarchical. There was a loss of freedom in dealing with corruption.”

They started to co-opt judges. The atmosphere among prosecutors became hierarchical. There was a loss of freedom in dealing with corruption.

Miloš Resimić, researcher, Transparency International

In the years since, Serbia’s dreams of joining the EU have withered, while Vučić and his allies are accused of hollowing out the country’s democratic institutions.

Despite some “substantial reform,” the European Commission noted in its 2024 Rule of Law report on Serbia, “political pressure on the judiciary and the prosecution service remains high.”

If anyone faces consequences after KRIK’s investigations, it’s the journalists themselves. Reporters at KRIK have dealt with everything from death threats from anonymous online trolls to front-page attacks from pro-government tabloids and a bevy of legal cases aimed at silencing their work.

The journalists, however, remain undeterred.

“I see this as my mission,” says Pećo. “At least I can show the citizens what’s really happening and they can be aware of the behaviour of those in power and their wrongdoings, so it’s all written somewhere so we will not forget about it.”

“We still hope, all of us, that they will be punished for all of the corrupt deals that they were involved in.”