Reported by

My name is Aida Cerkez, and today I was diagnosed with an acute stress reaction to war — several decades after I covered the siege of Sarajevo as a journalist for the Associated Press.

Although the World Health Organization says about 70 percent of Sarajevo’s population suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder due to the war following the breakup of Yugoslavia, which lasted from 1992 to 1995, I walked out of the siege with seemingly no “baggage” whatsoever.

That all changed in August. I came across a video of Abdullah, a four-year-old boy from Gaza, shown crying on camera. “Ana jeyaan, ana jeyaan!” the boy screamed. “I’m hungry, I’m hungry!”

Suffering from malnutrition, Abdullah was evacuated to Turkey. Doctors there tried everything to save him. But by the time he arrived, his body was little more than a sad face, a swollen stomach, and four tiny sticks for arms and legs.

He died on August 19 — the last night I slept without pills, or for more than two hours. Abdullah was with us for a while, and then we killed him.

When the sun goes down, I flick through channels, searching for suspense series or comedies, making a list of what I’ll watch until dawn.

Because even in between movies and episodes, I hear: 'Ana jeyaan.’

Left: A screenshot from a viral video of Abdullah Abu Zarqa, a Gazan boy suffering from malnutrition.

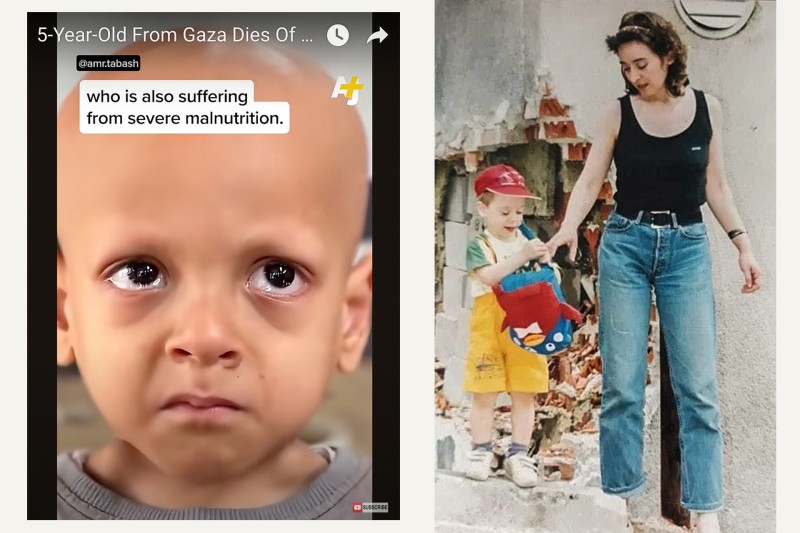

Right: Aida Cerkez with her two-and-a-half-year-old son in Sarajevo in 1992. He is holding a backpack she stocked for him with essential food supplies and identification documents in case she was killed in a bombing and he survived.

Then come the bombs, the bullets, the faces of my dead friends. The smashed head of my boyfriend in the morgue. Someone’s brain tangled in my hair after an explosion. The desperate screams for help from the wounded lying in the street — while we hid behind a wall, unable to move, knowing that was exactly what they wanted: to draw us out, then drop the second shell.

I hear my Motorola crackling: trlilit

“Bounty report!”

Bounty was my codename. My colleagues were worried.

“Bounty OK. Over.”

“Return to base when possible. Over.”

“Roger and out.”

The gunners missed me today.

The blood on my shoes. The brain in my hair. Scraping it into a handkerchief and burying it, with dignity, in the backyard. It was a piece of someone.

For more than 30 years, none of this came back to me. But it all returned, all at once, in August.

“Ana jeyaan, ana jeyaan, ana jeyaan” — all night long.

I pictured myself feeding Abdullah, then stroked my pillow, imagining he was drifting off to sleep with a full stomach. I apologized to him a thousand times. It didn’t help.

Then came another story: the tale of a journalist in Gaza and the suffering his family has endured. My editor asked if I could work on it. I read it. I vomited. I cried. My mother forced me to see a doctor. The family doctor sent me straight to a psychiatrist.

Four handkerchiefs later came the expected questions:

“Are you thinking about taking your life?”

No.

“Do you have the urge to break your fingers?”

What??? No.

But when I admitted that I had just cried because I could not find a parking spot, and that two days ago I burst into tears because there was no peanut butter in my supermarket, she stopped me.

“You will immediately turn off the TV, your phone, your computer. These pills will make you sleep. You have to sleep!”

Do you like shopping?”

No.

“What do you like?”

I don’t know.

In the diagnosis field, she wrote F43.2, followed by the names of two medications and a list of instructions. Nature. Sleeping … “See you in three weeks.”

F43.2 is the diagnostic code for an acute stress reaction, a form of post-traumatic stress disorder. But I don’t need to know this. I know the name of my disease: war. It never leaves you, even if you think you’ve left it behind.

But I will come back. Fresh, determined, and I will try to report about everything that’s wrong in the world. I’m a journalist and that’s how my life makes sense. And I’ll report about Gaza.

I want Abdullah to haunt the world forever.

Aida Cerkez preparing to report from the front lines in Sarajevo in 1992.