One summer afternoon in June 2022, five men calmly walked into a ground-floor apartment in Marbella, a swanky beach town on Spain’s sunny Mediterranean coast.

Only four of them would come out alive.

The following evening, the battered corpse of Aleksandar Kolundzic, a 33-year-old Serbian who had settled in Germany, was found by a property manager gagged and bound to a chair inside the apartment, which sits in a gated residential complex a few minutes’ walk from the sea. According to Spanish police, Kolundzic’s head had been wrapped in plastic and he was beaten for hours with golf clubs before being shot in the head.

“It was a full-blown execution,” a Spanish police source who was involved in the investigation told OCCRP. (The officer was authorized to speak to the press, but not to be identified by name.)

Nearly two years after the horrific killing, the first suspect in connection with the murder was extradited from Turkey to Spain and detained there in April. Spanish police allege that the 32-year-old German citizen of Turkish origin, identified here as Tolga S., was part of the group that tortured and murdered Kolundzic. While authorities hunt for the other suspects, Tolga S. is being investigated for murder, illegal detention, illegal possession of weapons, and membership in a criminal organization.

Both Kolundzic and his suspected killer were allegedly involved in organized crime, according to Spanish and German authorities. But there was one big difference: Kolundzic was also a police informant.

Alongside partners Paper Trail Media, Der Spiegel, and ZDF, OCCRP has pieced together new details about Kolundzic’s dangerous double life as an alleged drug trafficker and a collaborator with German police, and how it ended in his gruesome murder.

The reporting, which builds on revelations first reported by German broadcasters WDR and NDR, is based on thousands of documents reporters obtained from German prosecutors’ investigation into the murder, as well as court case files and interviews with police in Germany and Spain.

The German Investigation Files

It is a story of blurred lines, of an informant who was prized by German police for his accurate intelligence on criminal networks, but also suspected of enabling major drug deals. Testimonies gathered by police and prosecutors suggest Kolundzic owed drugs and large sums of money to some of his associates, a situation that may have made his work as an informant even more untenable.

CCTV footage of the arrested suspect, Tolga S. (center), in Marbella, Spain.

While law enforcement agencies in some countries allow informants to commit crimes with official authorization, the rules in Germany are more restrictive. Though Germany lacks a specific law governing the use of informants, according to experts and a ruling from the country's top court, police protocols stipulate that such sources should not be permitted to participate in criminal offenses themselves, raising questions about the extent to which Kolundzic’s handlers knew of his double life.

It’s also unclear whether German police adequately managed the risk Kolundzic faced. According to testimony given to police and prosecutors after his death, Kolundzic’s police handlers knew of his plan to go to the fateful meeting in Marbella, but they said they didn’t know the details of his travel plans — and appeared not to have asked many questions about them.

They said Kolundzic had traveled to Spain on his own "initiative," even while acknowledging that the goal was for him to gather evidence against Tolga S., whom German police had identified as a member of a Hells Angels gang.

Kolundzic had promised to brief the officers after his trip. He never returned.

"Nobody would have dreamed that it would end like this," said one of the German officers responsible for working with Kolundzic, according to testimony collected in the prosecution files.

"It hit us completely out of the blue."

While authorities have not yet established a motive for the killing, the story circulating in Marbella’s criminal underworld, according to Spanish police, is that Kolundzic had been exposed as an informant during the gathering inside the apartment.

But when German prosecutors tried to investigate the possibility that Kolundzic’s messages with his German police handler had been discovered by his killers, they hit an impasse: No phones were found at the crime scene, and a few days after the death, Kolundzic’s lead police handler had reset his own mobile phone to factory settings, deleting his communications with the informant.

Germany’s Interior Ministry and the Frankfurt Police, where Kolundzic’s handlers worked, declined to answer queries sent by reporters, including about the results of an inquiry that was launched into whether the officer’s decision to erase the messages constituted “criminal conduct.”

A lawyer representing Tolga S. also did not answer questions from reporters, other than to note that the investigation in Germany had been closed.

A Particularly Savage Murder

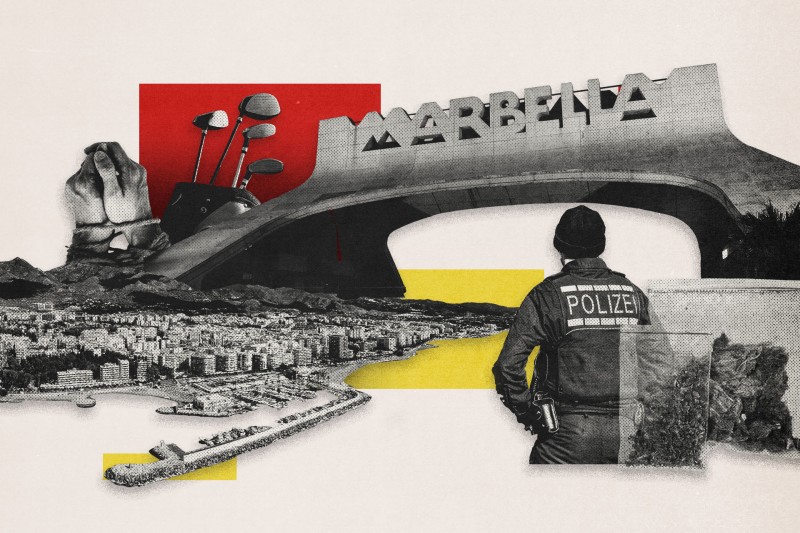

Marbella is a city with two faces — an apt setting for a man leading a double life.

Against the backdrop of the glittering Mediterranean Sea, the glamorous jet set party on their yachts, golfers putt on immaculate greens, and tourists stretch out across miles of sandy beach.

But the Andalusian holiday destination has also long been a magnet for gangs from around the world, whose battles for supremacy often end in bloody shootouts. The city has been described by Spanish police as the “U.N. of organized crime,” attracting criminals with its luxury offerings and strategic location near Spain's entry points for hashish and cocaine.

The apartment where Aleksandar Kolundzic was killed is located in Golden Beach in Marbella, Spain.

While Kolundzic was a regular visitor to Marbella — he had even registered at a local gym under a false name — he chiefly resided outside Frankfurt in the city of Offenbach, according to the German investigation into his death.

Known to his friends as Goran, he lived in Offenbach with his wife, who also hailed from his hometown of Novi Sad in northern Serbia. They had two children, and were expecting a third, when Kolundzic was killed.

In testimony given to German police, Kolundzic’s wife said her husband worked as a driver for a caregiving service and trained regularly in a martial arts gym. While she mentioned that he had occasional arguments with other men after a few drinks, she was not aware of any serious threats, or what her husband did when he was traveling, which was often to Spain.

She appeared to have no idea about his other profession: working as a confidential informant for Frankfurt police since at least 2018.

It is unclear how the collaboration started, but Kolundzic was considered by German police to be a “V-person,” the term used for an insider who secretly provides intel to authorities. The V refers to the German words for connection (Verbindung) and trust (Vertrauen).

According to the testimony of his police handlers in Frankfurt, Kolundzic told two officers of his plans to go to Spain to meet Tolga S., whom he claimed was a drug trafficker.

The handlers testified that Kolundzic told them that Tolga S., known by associates as “the fat one,” had been sending trucks carrying hundreds of kilograms of marijuana to Germany on a weekly basis. While the exact nature of their relationship is not known, Kolundzic said he had previously met Tolga S., according to his main handler.

Spanish police said the pair met again at a beach bar in Marbella the day before the murder. Precisely why the four men turned on Kolundzic the following day, and in such brutal fashion, is still under investigation. In their press statement, Spanish police said that “disagreements between the parties” had led to the victim’s hours-long torture.

The Spanish police source involved in the investigation told OCCRP it appeared the attackers wanted to extract information from Kolundzic.

“You don't torture a person so savagely just to settle a score or a debt,” he said.

German police also found that messages were sent from Kolundzic’s phone on the evening he was tortured.

It is unclear whether Kolundzic himself typed the messages, which were sent after a video had already been circulated to people he knew, showing him alive but tied to a chair, with his legs wrapped in foil, and a plastic sheet laid out underneath.

A plastic bag found by Spanish police at the crime scene in Marbella, Spain.

According to the German investigation files, Kolundzic’s wife said she received a message from her husband at 10:19 pm saying: "I'm leaving," followed by a smiley kiss.

An hour later, after she was already asleep, another message arrived asking for the number of a family friend. Kolundzic’s wife sent him the number at 3 a.m., but the message did not get through to his phone.

By that time, her husband had been dead for about an hour, according to police.

Kolundzic’s body was found the following evening by a person managing the apartment, where police also discovered handwritten notes listing amounts of drugs and money alongside names. The murder weapon, a fourth-generation Glock 19, was discovered by sanitation workers in a nearby trash can.

CCTV footage captured four men leaving the apartment, one of them carrying several mobile phones in his hands. Tolga S. and the other three suspects later fled to Turkey, according to the German files.

Spanish police said they were able to link the suspects to the murder scene partly through fingerprints: Tolga S. was already on a police database after being briefly arrested in Madrid in 2021 for carrying falsified identity documents. In the announcement of his arrest, police described him as the “leader of a drug trafficking network with branches in southern Spain,” and said he had been extradited for his suspected involvement in Kolundzic’s death.

A Dangerous Game

Kolundzic’s chief handler in Frankfurt told police and prosecutors investigating the murder that he met with Kolundzic around every three weeks. His tips were always verifiable and led to successful investigations, according to a note in an investigative file.

But the new material reviewed by reporters suggests Kolundzic’s position was becoming increasingly precarious in the lead-up to his murder, raising questions of whether police bungled their handling of him.

For instance, an individual described as a close confidant testified to police that Kolundzic had told him about drug debts totaling several hundred thousand euros in a phone call three days before his death. This associate said he also received several calls from a Spanish number, in which a Bosnian speaker demanded he "release drug money from Kolundzic," according to the testimony.

Another person interrogated by German police said he had been asked to look for Kolundzic in Offenbach by two individuals who said he owed them “800,000 euros and an unknown amount of cocaine."

And a third witness, who said she had introduced Kolundzic to Tolga S., told police during a search of her apartment that the latter was angry with Kolundzic because he had not repaid a 100,000 euro debt. (The woman later declined to give official testimony.)

When interrogated after his death, Kolundzic’s handlers said they were not aware of any threats against the informant.

As reported by German broadcasters WDR and NDR, there is also evidence that Kolundzic was breaching the German police protocols that bar informants from participating in criminal activities themselves — though whether his handlers were aware of his activities could not be confirmed.

In a case pursued in 2020 in Giessen, a German town north of Frankfurt, Kolundzic was investigated “on suspicion of illegally importing a not insignificant amount of narcotics,” the prosecutor's office confirmed to reporters.

The case files of another investigation pursued by prosecutors in 2021 cite intercepted chats showing Kolundzic, who went by the alias “Professor,” allegedly coordinating numerous deliveries of several hundred kilograms of marijuana. The investigators identified him as the communication link between an alleged drug courier and recipients.

At the time, Giessen prosecutors were unaware that Kolundzic was an informant — or that it was a tip he gave to his Frankfurt handler that had sparked the second investigation.

“The public prosecutor's office in Giessen was only informed of Mr K.'s VP status after his death,” a spokesperson for the public prosecutor’s office told reporters, using the acronym for V-Person.

“Due to the death of Mr K., the proceedings against him were subsequently discontinued.”

Kolundzic’s lead handler, who declined to comment when reached by reporters, is scheduled to testify during the trial for the second case in Giessen, where six other suspects were indicted on charges of large-scale drug trafficking in late March 2023.

An image from German police files identifying the arrested suspect, Tolga S., captured by CCTV footage.

While Kolundzic was not known to Spanish police before his murder, a Spanish investigator told OCCRP they later learned he had met in Catalonia with individuals connected to the Kavač mafia clan from Montenegro, which is heavily involved in drug trafficking. In their press release about the arrest of Tolga S., Spanish police described Kolundzic as being “linked to Balkan criminal organizations.”

Police Chats Erased

The lack of a specific law governing the use of confidential informants in Germany has become the subject of debate in recent years. Legal experts have argued such regulations are long overdue, while some police have expressed concern new rules could curb the efficacy of a powerful investigative tool. A new law on the use of such informants is currently making its way through the legislative process.

Yet according to a legal opinion commissioned by Germany’s Justice Ministry in 2017, which weighed in on whether the use of confidential informants required further regulation, in practice police are already supposed to ensure that informants do “not themselves participate in criminal acts despite their proximity to the criminal milieu.” Germany’s Federal Court of Justice also ruled in 2020 that informants must not be permitted to commit crimes, but that they can — with the consent of prosecutors — observe crimes without intervening in order to investigate more significant illegality.

Any informant found to be dealing drugs on a large scale would no longer be considered an appropriate collaborator, an experienced German police handler of informants confirmed to Der Spiegel on the condition of anonymity.

What Kolundzic’s police handlers knew about his alleged involvement in drug trafficking may never be known. German police’s attempts to retrieve the erased messages from his lead handler’s phone were not successful, according to the investigation files. In his interrogation, the officer said that he regularly deleted his chat histories as a security measure — a measure he carried out without supervision.

The Frankfurt criminal investigation department did not answer questions about whether any of the communication records still existed in another format.