Reported by

In the northwest Nigerian state of Kano, vast swathes of farmland dedicated to cotton, grain, nuts, and beans are the backbone of the local economy.

Most farmers working on the patchwork of green and gold fields are smallholders, like Abdulwahab Tsoho Adamu, 56, who grows maize and beans for the local market on a farm in the community of Tassa.

To control the weeds among their crops, Adamu said many locals make use of two herbicides, atrazine and paraquat — even though the chemicals have been banned in Nigeria for the past two years over concerns about their impact on health and the environment.

Nigerian authorities have described paraquat as “highly toxic to humans and the environment” and said that atrazine has also been linked to negative physical effects, including on the human reproductive system. The chemicals have long been banned in dozens of countries, including throughout the European Union.

Farmer Abdulwahab Tsoho Adamu says he has tried to minimize his use of toxic herbicides atrazine and paraquat, but that they are still widely available in Nigeria despite a ban.

Adamu said he had tried to minimize his use of the products after concerns over their toxicity, but many farmers still used them because they were effective — especially in the rainy season, when weeds flourish. “If you spray paraquat today, by the following morning it should have killed all the weeds on the farm,” he said.

They also continue to be easily available, despite a government ban from importing the chemicals that has been in effect since 2023 for paraquat, and 2024 for atrazine.

OCCRP reporters found that 37 shipments of atrazine and paraquat arrived at major Nigerian ports in 2024, after the ban on both chemicals came into effect. Almost all of it was brought in by two subsidiaries of local Chinese companies, according to import records from commercial database Volza.

Although Nigeria's National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) has raided shops and local markets across Nigeria in the aftermath of the bans, looking for contraband products and even making some arrests of vendors, the larger-scale importers were able to bring in the herbicides unimpeded.

When asked about the imports uncovered by reporters, NAFDAC said it had permitted some companies that had experienced shipping delays to import atrazine and paraquat even after the ban was supposed to be in place — “strictly under the condition that the products are exhausted within the designated moratorium period, which ends in 2024.”

However, previous public statements made by NAFDAC in 2022, 2023, 2024, and even earlier this year, mentioned no such provision for delayed shipments. The moratorium period for the use of paraquat was already over by the end of 2023.

Donald Ofoegbu, lead coordinator at the Alliance for Action on Pesticide in Nigeria, a group that advocates for improved pesticide regulation, said NAFDAC should not have allowed any permits or exemptions.

“If NAFDAC has phased out and banned a pesticide, it cannot go back and approve its import for the local market,” Ofoegbu told OCCRP. “Considering NAFDAC's … poor capacity to effectively monitor and enforce the law and regulations on pesticides, [it] should not be seen giving permits to anyone … to import banned pesticides."

Mohammed Yahaya, a professor of Agricultural Extension at Nigeria’s University of Ibadan, said law enforcement and regulatory agencies had failed to do their jobs by allowing the flow of these agrochemicals into Nigeria.

“[The importers] don’t care about the consequence or implication on the citizens,” he said.

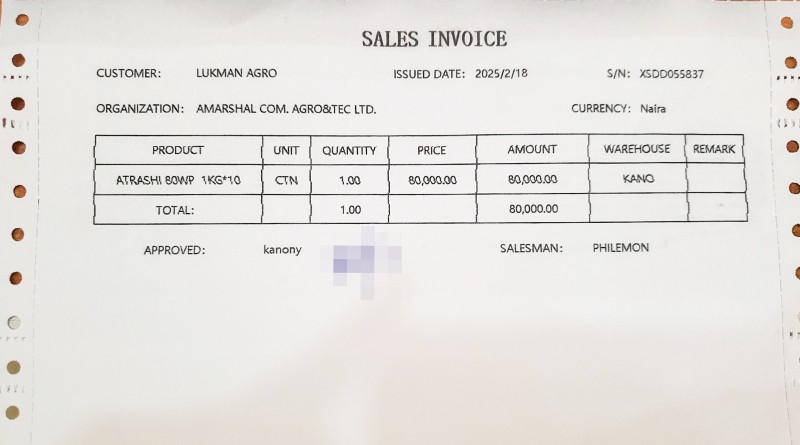

A sales invoice for a carton of Atrashi, a brand of atrazine, sold at the warehouse of Amarshal Com. Agro and Tech Limited in Kano, Nigeria, on February 18, 2025.

Banned Chemicals Flood In From China

Almost all the atrazine and paraquat that was imported into Nigeria in 2024 originated in China, with the total value of the shipments at around $5 million, according to data. Atrazine accounted for some $4.2 million, and paraquat the rest.

The vast majority of the imported herbicides — almost 90 percent — were brought into Nigeria from China by Amarshal Com. Agro & Tech Limited and June Agrochemical Nigeria FZE. Both are Nigerian operations of Chinese firms: Amarshal is majority-owned by Ningbo Double Fusion Imp & Exp Co., Ltd and June Agrochemical is part of the YMDY Group. Three Nigerian-owned companies accounted for the remainder of the 2024 imports.

Amarshal Com. Agro and Tech was by far the biggest importer of atrazine into Nigeria in 2024, bringing in seven shipments from China between January and March, valued at $3,287,482.08.

The fate of these shipments is unclear, but reporters found that atrazine brand Atrashi was still on sale at Amarshal’s warehouses in Kano city in both November last year and February this year, after NAFDAC’s moratorium on its sale and use had ended.

Amarshal Com. Agro and Tech Limited's warehouse in Kano, Nigeria, during a visit in November 2024.

Heaps of Atrashi and other agrochemicals towered to the roof of the warehouse. The reporter managed to buy a carton of the chemical for 80,000 naira (around $53) on each visit.

Amarshal Com. Agro and Tech is a subsidiary of Ningbo Double Fusion Import and Export Co., Ltd, a company based in the industrial city of Ningbo in eastern China. Ningbo Double Fusion is listed in the Volza import data as one of two Chinese exporters of the atrazine received by Amarshal.

Amarshal and Ningbo Double Fusion did not respond to requests for comment.

Another Chinese-owned chemical firm, June Agrochemical Nigeria FZE, based in the Lekki Free Zone in Lagos, imported 22 shipments of paraquat worth nearly $600,000, almost all from China, in April 2024. The same year, it also received four imports of atrazine worth more than $317,000.

The company is part of the Chinese group YMDY, which also has companies operating in Ghana, Mali, Cote d'Ivoire and the U.S, according to its website.

It is not known what happened to the paraquat brought into Nigeria by June Agrochemical in 2024, but NAFDAC told OCCRP that it had issued an import permit to the firm in error.

“The permit granted to June Agrochemical Nigeria FZE was inadvertent and an oversight. They are not supposed to have a permit to import the items into the Customs Area because the company is registered to the free trade zone. The permit will expire 31st December 2025,” NAFDAC said.

June Agrochemical and YMDY did not respond to requests for comment.

Nigerian Importers Also Brought In Banned Weedkillers

‘Banning on Paper Does Not Guarantee Enforcement’

The result of these imports? In Nigeria, paraquat can still easily be bought from uncertified dealers and street vendors, and there is a lack of training on how to safely use it, said Ambali Suleiman, a professor of environmental toxicology at the University of Ilorin in Nigeria.

In addition to inadequate regulatory implementation of the import ban, he said farmers still lacked awareness about the danger of the chemicals to people and the environment — and that Nigerian regulators had not been able to recommend suitable alternatives.

“[The] ban on herbicides must be enforced using multifaceted strategies that include strong legal frameworks, efficient enforcement systems, and public awareness initiatives,” he said.

Back in Kano, farmer Muhammad Khamis said that locals often had little idea of the harms that banned chemicals could cause, and did not always protect themselves.

Farmer Muhammad Khamis spraying his crops in Kano, Nigeria, on November 12, 2024.

“I do use protective equipment, such as eyeglasses, gloves, helmets, face mask, and boots, but not always,” said Khamis, 49, who grows beans for the local market in Tamburawa community.

Adewoye Olayinka, a professor of environmental toxicology and aquatic pollution at Ladoke Akintola University of Technology in Nigeria, said that without active collection or buy-back programs, as well as rigorous enforcement, atrazine and paraquat would continue to circulate because they were “cheap and effective.”

“Banning a chemical on paper does not guarantee enforcement,” he said. “Regulatory agencies such as NAFDAC or the Federal Ministry of Agriculture may lack the resources, personnel, or infrastructure to effectively remove banned products from markets, especially in rural areas.”