For the past eight years, Russia and its fellow U.N. Security Council members have maintained economic sanctions on North Korea over its nuclear testing, including severe restrictions on selling crude oil and refined petroleum exports to the isolated dictatorship.

The 2017 sanctions limit total exports of oil products to North Korea to 500,000 barrels per country per year. But an investigation last year by the Open Source Center, a U.K.-based research group, estimated that Russia shipped more than double the annual limit to North Korea over just nine months last year.

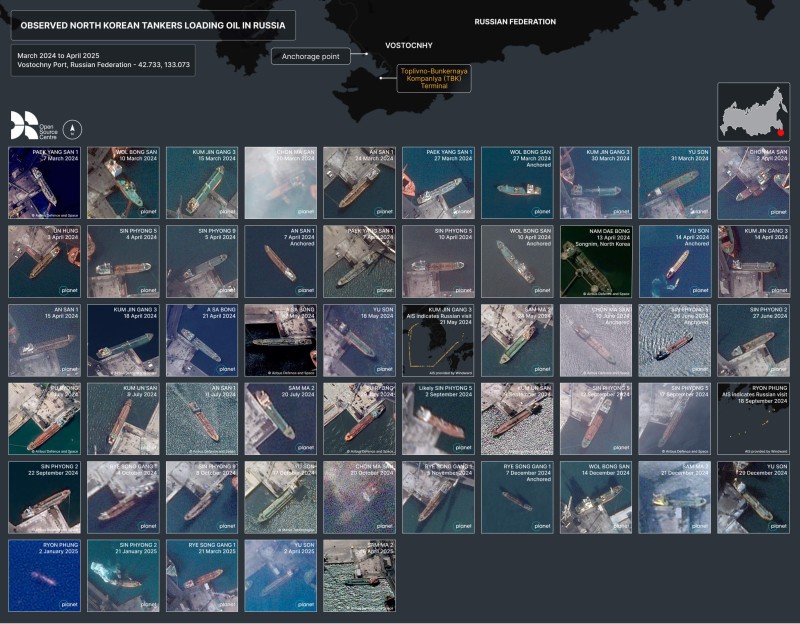

That investigation was based on satellite imagery that, according to the Open Source Center, showed North Korean tankers making more than 40 trips to a port in the Russian Far East, and carrying an estimated 1.3 million barrels of petroleum products.

The satellite imagery that helped the Open Source Center conclude that North Korean tankers were carrying Russian oil from a port in the Far East.

Now, leaked financial records obtained by OCCRP’s Russian partner, IStories, together with the Open Source Center, reveal new details about the secretive payment channels that facilitate those Russian oil exports.

These channels include a Moscow fuel-trading firm; a Far Eastern Russian oil exporter that says it specializes in selling beer; financial intermediaries in the United Arab Emirates (UAE); and a Vladivostok company that was paid in cash.

The records also reveal details about Russian companies involved in shipping oil by land to North Korea and the companies there listed as the recipients, including an alleged front for North Korea's main arms exporter.

Russian President Vladimir Putin walking alongside North Korea’s supreme leader Kim Jong-un on a visit to Pyongyang in June 2024.

As Russia itself has become more isolated since its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, it has expanded its economic and security ties with North Korea into a full-fledged partnership in which Pyongyang even provides soldiers and weapons for Russia’s war on Ukraine.

“To keep fighting in Ukraine, Russia has become increasingly reliant on North Korea for troops and weapons in exchange for oil," David Lammy, then Britain’s Foreign Secretary, told the BBC last year.

Pyongyang’s embassy in Moscow did not respond to a request for comment. Russia, although it is still formally a party to the U.N. sanctions, has publicly called them “detached from reality."

‘Only Thinking About Ukraine’

Far Eastern Terminal

In early March 2024, the North Korean tanker Paek Yang San 1 docked at an inconspicuous oil terminal near Vostochny Port, a key maritime cargo hub in Russia’s Far East.

It was an unusual port of call for a vessel openly flying the flag of North Korea, whose government has long used concealing tactics to operate what is known as a “shadow fleet” to circumvent international sanctions. The tanker was loaded up with petroleum products and soon sailed back to North Korea.

A view of Vostochny Port in the Russian Far East.

It also caught the eye of authorities. In April 2024, the White House accused Russia of breaching the sanctions, claiming that Russia had delivered 165,000 barrels of refined petroleum to North Korea from Vostochny in March 2024 alone.

And in May of that year, several Russian companies were hit with sanctions by the U.K. over what London called the “arms-for-oil trade” with North Korea. One of them was Toplivno-Bunkernaya Kompaniya (TBK), which operates out of Vostochny Port and is based in the nearby city of Nakhodka.

Now, leaked bank records from TBK obtained by IStories reveal links to a previously unknown entity in the supply chain, a Moscow-based fuel-trading company called Southern Railway Expedition (SRE).

TBK received regular payments from SRE in 2024, including for “storage” and “transshipment,” whose timing strongly correlates with the movement of the petroleum products flagged by the Open Source Center investigation.

SRE’s first 2024 transfer to TBK — just over 21 million rubles ($229,200) — was made in late February, two weeks before Paek Yang San 1 entered Vostochny Port.

Four more transfers totalling 115 million rubles ($1.26 million) followed in March and April, a period when North Korean ships called at the Russian port 23 times.

SRE made 11 more transfers totaling nearly 108 million rubles ($1.15 million) during the remainder of the year, when North Korean tankers made another 27 trips.

Reporters were unable to obtain further evidence clarifying whether North Korea directly purchased the oil from SRE or if other intermediary companies were involved in the chain.

TBK did not respond to e-mailed questions about its ownership, its work with SRE, or the shipments to North Korea.

All of the payments were routed through two banks: 158 million rubles ($1.7 million) went through TsMRBANK, a Russian bank that the U.S. government sanctioned in 2017 for working with pro-Russian separatists in Ukraine and more recently accused of dealing with North Korean entities. The rest was routed through Promsvyazbank, a Russian state lender closely affiliated with the Russian Defense Ministry that also provided SRE with a loan of almost 1 billion rubles (around $9 million) in 2024.

SRE's Suppliers

Registered in 2019 as a wholesale fuel trading company, SRE saw its revenues explode in 2024, jumping to 18 billion rubles ($194 million) from just under 900 million rubles ($10 million) the previous year.

The company has no public-facing website, and there is little public information about its owner, Nikolai Gerasimenko, who is a shareholder in other fuel-trading companies. These include Energotrade Kalmykia, in which Gerasimenko partners with Ruslan Agayev, the son of Bekkhan Agayev, a federal lawmaker from Russia’s southern Chechnya region.

The Agayev family is close to Kadyrov, the ruthless Kremlin-backed former warlord who runs Chechnya like a personal fiefdom, and made its fortune in the early 2000s in the petroleum trade.

Neither Gerasimenko nor SRE responded to requests for comment.

Sudden Millionaires

Customs records obtained by IStories show that Russia has also sent petroleum products to North Korea by land via the Khasan-Rajin railway, built in 1952 at the height of the Korean War, in which the Soviet Union backed Pyongyang.

Russia shipped at least 315,000 barrels of petroleum products to North Korea via this railway in 2024, the records show, with several Russian companies involved in the exports.

The launch of a restored section of the Khasan–Rajin rail connection in North Korea in 2008.

One of the largest exporters was a company based in the Far Eastern city of Vladivostok called Inrostopt, whose main business activity, according to official company records, is beer sales.

Like SRE, Inrostopt has seen a dramatic rise in its revenues. In 2021, the company reported revenues of just 1.5 million rubles (around $20,000). That figure soared to 666 million rubles (approximately $7 million) in 2024, when it shipped 85,000 barrels of petroleum products to North Korea by rail.

Inrostopt's owner is businesswoman Natalya Bondar, who previously ran a sole proprietorship trading in meat and vegetables. She did not respond to a request for comment.

Inrostopt used at least two companies based in the United Arab Emirates to process payments for oil shipments under contracts with North Korean companies. One of the firms, Amax General Trading, is owned by Russian businessman Amiran Akhmetshin. The other is SGravity General Trading, owned by Kyrgyz national Avval Ganzhibaev.

Leaked banking records show that Amax paid Inrostopt 80 million rubles ($867,000) in 2024, while SGravity paid the Russian company nearly 328 million rubles ($3.5 million) in the same year. The two UAE companies acted as intermediaries between the Russian firm and its North Korean buyers, the records show.

Amax and SGravity, whose Russian-language websites state that they offer payment intermediary services, did not respond to requests for comment in time for publication.

Another company supplying oil to North Korea, Vladivostok-based Atlant Export, was registered in 2023 and in 2024 already reported revenues of 680 million (around $7.3 million).

Several times a month last year, Atlant Export accepted large sums of money — amounting to tens of millions of rubles — as cash deposits into the company's accounts at bank branches in Russia’s Far East. The payment descriptions indicate they were for “KORUS” contracts for the supply of petroleum products.

It is unclear what KORUS refers to in these transfers. That acronym is also used for a free trade agreement between the United States and South Korea.

Atlant Export did not respond to a request for comment.

The North Korean Recipients

The customs data indicates the recipients of the petroleum products shipped from Russia by land.

More than 60,000 of the 211,000 barrels were sent to Ka The, which banking records describe as a “joint venture” registered in Pyongyang. There is little public information about this company, though it is mentioned both in customs data and in bank records for Inrostopt.

Another 40,000 barrels were shipped to a company based in Pyongyang called Future Electronic Company, which a U.N. expert panel in 2019 described as a “front company” for the Korean Mining Import and Export Corporation (KOMID), North Korea's main arms exporter. The U.N. blacklisted KOMID in 2009.

Nearly 44,000 barrels were sent to Okryu, a North Korean foreign-trade company that was hit with U.S. sanctions in December 2024. The U.S. Treasury Department sanctions said Okryu “received thousands of tons of oil shipments from Russia.”

Another listed recipient was a Russian-North Korean joint venture called RasonConTrans, which has been operating since 2008 and leases port facilities in Rajin, a North Korean port near the Russian border. A special railway line has also been laid there.

Correction: This article was updated on December 2, 2025, to reflect the fact that Mikhail Gutseriev’s son was the CEO of Forteinvest until 2021.