The US$ 2.9 billion Azerbaijani Laundromat was comprised of four bank accounts belonging to four shell companies registered in the United Kingdom, although more may have been involved. It was used as a slush fund and money laundering platform that paid European politicians and influencers and bought luxury goods and services for prominent Azerbaijanis. It may have been used for many other purposes as well.

But where did the money come from?

The scheme’s organizers tried hard to hide the origin of the billions that fed its accounts in the Estonian branch of Danske Bank. The secretive shell companies, fake beneficial owners, and shareholders they used were all designed to make tracing the funds impossible.

But leaked banking records obtained by the Danish newspaper Berlingske and shared with the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) exposes the probable involvement of Azerbaijan’s ruling elite in the fraudulent scheme.

Some of the money came directly from the Azerbaijani government. The country’s Ministry of Emergency Situations, Ministry of Defense, and the Special State Protection Service (the country’s intelligence service) chipped in a modest total of $9 million.

Another significant amount -- over $29 million -- was sent by Rosoboronexport, a Russian state weapons intermediary export company.

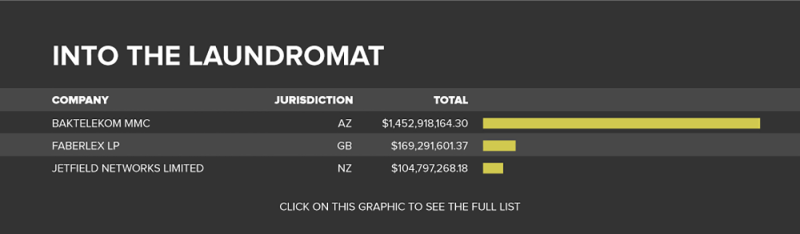

But almost half of the money, by far the largest share, came from an account held by a mysterious company at the state-owned International Bank of Azerbaijan (IBA). Baktelekom MMC, whose name mimics that of the mobile phone giant Baktelecom but which is not the same company, sent $1.4 billion.

The second and third-biggest contributors after Baktelekom were Faberlex LP and Jetfield Networks Ltd, two offshore companies with direct connections to the Azerbaijani regime and ties to a major corruption case involving a former Italian MP who prosecutors say was paid to work on behalf of Azerbaijan’s interests . (See: The Influence Machine)

Also contributing were real companies, many of which had large contracts with the Azerbaijani state. For example, Pano ASC, a construction company that does business with the government and the Heydar Aliyev Foundation, a cultural foundation started by the first family of Azerbaijan, put in $3.2 million. These companies may or may not have been aware that their money was going into a slush fund and money-laundering scheme.

Offshore companies, usually registered in the UK with proxy directors and shareholders, made up the rest of the Laundromat contributors, with payments of hundreds of millions more (some of them also took money out). The identities of the true beneficial owners of these paper companies are not known.

Some of these companies show up in other criminal cases. At least 33 of the companies that made transactions to or from the Azerbaijani Laundromat appear in OCCRP’s Russian Laundromat investigation. This was a massive operation based in Russia, Latvia, and Moldova that laundered and moved offshore some $20 billion of Russian money.

The Well-Connected Mimic

Baktelekom MMC was the mysterious largest contributor that used an account at IBA to transfer $1.4 billion into the Azerbaijani Laundromat. It is not clear where Baktelekom’s money came from -- loans from the government, the Azerbaijan Central Bank, or the IBA itself.

What’s clear is that it didn’t earn it. The company has no website and no evident commercial activity, making it highly likely that it was not the original source of the money, but rather a holding vehicle for money that came from elsewhere. The company’s name appears to be designed to confuse people and make them think it’s related to Baktelecom, a major Azerbaijani mobile phone operator (the names differ by one letter).

There are reasons to believe that Baktelekom is connected to Azerbaijan’s ruling clique. The company was founded by Rasim Asadov, the son of the country’s first post-independence Minister of Interior Affairs. OCCRP has previously documented Asadov’s connections to the regime. He is a business partner of the cousin of Azerbaijan’s first lady, Mehriban Aliyeva and his brother, Natig Asadov, is a Sabali district prosecutor in Baku. Asadov could not be reached for comment.

The former president of IBA, Jahangir Hajiyev, who is currently incarcerated in Prison 13 in Baku, told OCCRP via his lawyer that he was not aware of the bank transfers made by Asadov or Baktelekom MMC.

This is hard to believe, given the volume of money Baktelekom handled in its IBA accounts and the frequency of the transactions. The company transferred money into the Laundromat 530 times in 2013 and 2014, with transactions occurring every other day and sometimes even three times in one day. The smallest single transfer was just $138,000 while the largest was over $6 million, with the total amounting to $1.4 billion over that period.

The second-largest contributor was Faberlex LP, a UK company that sent in over $169 million. According to Italian prosecutors who investigated Luca Volonte, an Italian MP, for corruption related to his lobbying for Azerbaijan, Faberlex LP is owned by Maharram Ahmadov, 51, an Azerbaijani citizen who also owns, on paper, two of the core Azerbaijani Laundromat companies, Hilux Services LP and Polux Management LP. Registration documents filed with the UK company registry confirm that Faberlex, Hilux, and Polux share two of the same secretive offshore companies as shareholders.

Ahmadov’s passport, personal details, phone number and signatures are attached to the dossier that Hilux and Polux filed to open the accounts.

The problem is that Ahmadov is not a billion-dollar financier and businessman. He is actually a modest driver in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. He lives in a humble makeshift home in the Gushchuluq neighborhood, an area of small poultry farms on the outskirts of the capital.

Ahmadov’s role was to hide the true owner of the Laundromat companies and to act as a front for the organizers of the operation.

The third-largest contributor to the Laundromat, to the tune of $105 million, is Jetfield Networks Limited. According to Italian prosecutors, a company with the same name was used by Elkhan Suleymanov, an Azerbaijani parliamentarian who represents the country in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), to pay Luca Volonte, a former member, for his efforts to improve Azerbaijan’s image abroad.

Azerbaijan’s Main Bank

IBA, which clearly played a pivotal role in the Laundromat, is also a big player in the Azerbaijani economy. It is the largest retail bank in Azerbaijan by loan volume, providing loans, credit, deposits, and current accounts to nearly 750,000 customers. This is a significant number in Azerbaijan, a country with less than 10 million inhabitants.

It is possible that Baktelekom’s money came from IBA loans, which have a problematic history.

In 2015, Azerbaijani authorities started arresting businessmen who were failing to repay loans from the bank. The CEO of the IBA himself, Hajiyev, ended up behind bars after a 20-year tenure with the bank. He was sentenced to 15 years in jail for misappropriation of funds, abuse of power, forgery, and other accusations. Other IBA executives also went to jail.

Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Finance blamed the former CEO and his staff for the bad loans: "Between 2009 and 2015 about 1.3 billion AZN, $1.4 billion and €300 million in loans were given illegally,” a ministry spokesman said. “Most of them were problematic loans. … sent to unknown offshore companies. … At the same time, by the instructions of the bank’s former management, about $3.7 billion and €1.1 billion were withdrawn from the country."

During his trial, Hajiyev defended himself by pointing out that that he wasn’t the beneficiary of the loans that offshore companies received from IBA. Instead, he deflected responsibility to Azerbaijan’s ruling elite.

“The money they claim to be stolen was spent on [infrastructure] projects,” Hajiyev said. “Today those projects are in their hands and they don’t provide documents.”

"After my resignation I cooperated with prosecutors. I gave them all the information. But, unfortunately, they didn't want to investigate it. I know they went to London but didn't find anything,” he said.

OCCRP reporters found one Azerbaijani businessman who used the services of IBA and the Laundromat.

“As the oil prices went down, the pie got smaller and infighting started between the oligarchs. People got arrested but everybody was actually in it. Some just got lucky or had better protection. This was all done with the consent of the higher-ups in Baku,” he told OCCRP. He asked not to be identified for this story.

Earlier this year, IBA filed for protection against its creditors in courts in the United Kingdom and United States after it defaulted on loan payments this spring. The bank owes more than $3.3 billion to Cargill, Credit Suisse, FBME, SOFAZ (Azerbaijan’s State Oil Fund), and other creditors. IBA’s representatives blame the bank’s troubles on falling oil prices, as Azerbaijan’s economy heavily relies on its natural gas and oil riches. The bank’s filings come after the bank had already been bailed out by the Azerbaijani government in 2015.

Neither Hajiyev, the bank’s CEO, nor the Ministry of Finance ever named the offshore companies they say got billions from IBA illegally, but some of them are likely to be companies that appear in the Azerbaijani Laundromat.

The Land of Fire

At least one businessman has claimed ownership of one of the four companies at the core of the Azerbaijani Laundromat, though there is no evidence to support this unlikely assertion.

Hafiz Mammadov is head of the Baghlan Group, one of the Caspian country’s largest business conglomerates. The group rose to international prominence this year when the New Yorker exposed its involvement in the development of the Trump Tower in Baku.

In 2014, when they pinned the “Azerbaijan-Land of Fire” logo on their chests, the players of RC LENS, one of France’s oldest football clubs, were unaware of the financial burden attached to the slogan on their red and yellow jerseys. One year earlier, the club had been bought by Mammadov.

He has pinned the same logo on the chests of Atletico Madrid’s players and tried to buy Sheffield Wednesday F.C., a British football club. Mammadov’s forays into the world of European football were an important part of Azerbaijan’s efforts to improve its international image despite the human rights violations that were taking place back home.

But, though he promised to invest big money in RC LENS, Mammadov failed to deliver in a timely manner. Beginning in 2014, he started postponing the investment payments he had promised to the club.

The Azerbaijani Laundromat came to the rescue. On Sept 18, 2014, one of its four core companies, Hilux Services LP, transferred $2 million to RCL Holding, the company that formally owned Hafiz Mammadov’s club.

According to its bank filings, Hilux stated it would be receiving money from the International Bank of Azerbaijan. But Hilux’s Estonian bank account at Danske Bank was owned by the blue-collar driver, Ahmadov, who was likely a proxy unaware how he was being used by the real masterminds behind the Azerbaijani Laundromat.

Gervais Martel, the president of RC Lens, and one of the club’s lawyers, Laurent Schoenstein, told OCCRP that the $2 million transfer represented one of the two payments agreed by Baghlan Group and Hafiz Mammadov for the 2014-2015 season.

“It’s a payment made by the shareholder of RCL Holding, which was called Baghlan Group, the parent company of Mr. Hafiz Mammadov, the shareholder of RC Lens,” said Schoenstein, adding that, when asked about the payment, Hafiz Mammadov told club representatives that Hilux was a company controlled by him and was part of his business group. “He made the payment through a company that was presented as a company controlled by him and part of the Baghlan Group, the famous company [Hilux] …based in Scotland,” the French lawyer added.

It’s not clear if Mammadov claimed the company was his to prevent further questions from his partners or if Baghlan truly did control Hilux. But, given the myriad of other types of businesses Hilux was involved in and the vast amounts of money it trafficked, it’s not likely that it was really controlled by Baghlan,.

On the day the RC LENS received the $2 million installment, $10.3 million was fed into Hilux’s Danske Bank account from the two biggest funders of the Laundromat. Faberlex LP contributed $2.8 million and Baktelekom MMC sent $7.6 million.

The club’s business relationship with Mammadov eventually turned sour as the businessman defaulted on his payments to the club. He complained to Azerbaijani media outlets that local banks refused to give him loans.

Madina Mammadova contributed to this story.

This story is part of the Global Anti-Corruption Consortium, a collaboration started by OCCRP and Transparency International. For more information, click here.