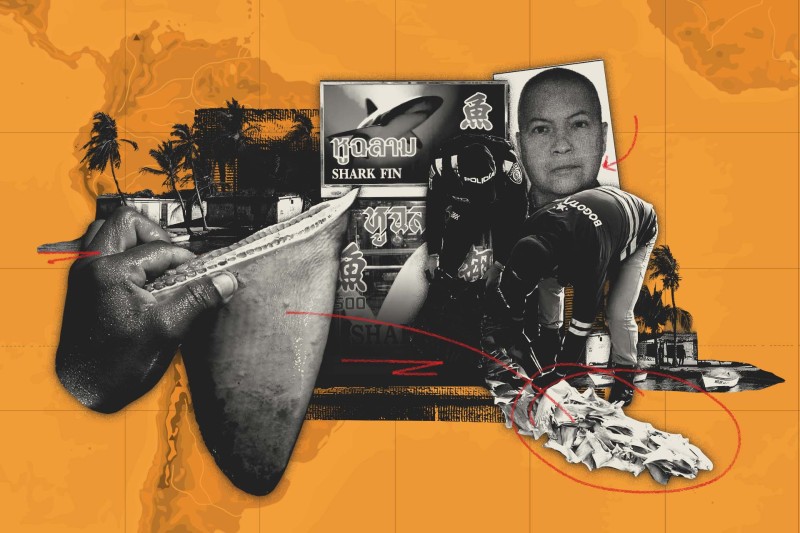

In September 2021, Colombian authorities intercepted an unusual shipment at Bogotá’s El Dorado airport: Nearly 3,500 shark fins destined for Hong Kong.

The fins, which are an expensive delicacy in Asia, were packed into cardboard boxes and hidden among more than 100 kilograms of fish bladders, Bogotá’s Environment Secretariat said at the time. Authorities estimated that between 900 and 1,000 sharks were killed to make the shipment, seized just six months after Colombia banned fishing and trading in sharks and shark parts.

Publicly, authorities did not name any of the people or companies involved in the shipment. But a leak of files from the Colombian prosecutor’s office shows that the man whose company sent the shipment to Bogotá was Fernando Rodríguez Mondragón, son of the late boss of Colombia’s Cali Cartel.

Drawing on prosecutors’ documents — corroborated with interviews, company registries, and property records — OCCRP and its partners, Mongabay Latam and Armando.info, traced the package from its origins in the northern coastal city of Maicao, and uncovered new details about where it was headed in Hong Kong.

A leaked spreadsheet from the prosecutor’s office shows that the shipment sparked an ongoing money laundering investigation, though the file did not identify the suspects. In September, the prosecutor’s office said the case was still in the investigation phase and declined to share more details.

Reporters also found that the shark fins had been dried and skinned using techniques rarely found outside Asia, which experts said could indicate that processing skills are being exported to Latin America.

“This is the first time that we are aware of a legal case in which fin processing took place in the nation where the sharks were caught, prior to them being exported,” an analysis of samples from the seized shipment by the biologist Diego Cardeñosa said.

On its way from Maicao, which is near the Venezuelan border, the package stopped in the town of Roldanillo in western Colombia where Rodríguez Mondragón’s company was registered, a three-hour drive from the Pacific coast.

Fernando Jiménez, director for crimes against natural resources and the environment at the prosecutor's office, said that Rodríguez Mondragón had been placed under house arrest for one year while the investigation into the shipment continued. He said Rodríguez Mondragón faced charges including wildlife trafficking. It’s not clear when the house arrest began.

Contacted by reporters, Rodríguez Mondragón said that he would prove himself innocent. “I am gathering conclusive evidence that will show that I had nothing to do with the shipping of this cargo to Hong Kong,” he said.

He blamed the shipment of illegal shark fins on a Chinese employee of his company, who he said committed an “abuse of trust” and sent the shipment without his consent while he was recovering from Covid-19.

Rodríguez Mondragón also shared two videos he said were taken by his company’s security cameras showing two men cleaning shark fins and moving them between containers. He said the prosecutor’s office had possession of the videos, but did not give further explanation or context.

Reporters attempted to contact the Chinese employee at the email address listed in his visa application, but did not receive a response.

Fishy Cargo

A Pitstop in Roldanillo

The seized shipment left Maicao for Roldanillo on August 23, 2021, prosecutor's documents show. Its recipient was listed as a local company, Comercializadora Fernapez S.A.S., which was opened in 2017 and dedicated to “wholesale trade in agricultural raw materials and live animals.”

Corporate records show that the company is owned by Rodríguez Mondragón.

Rodríguez Mondragón is also known as “the son of the chess player,” after the title of a book he published in 2007, telling the story of the Cali Cartel from the inside. Rodríguez Mondragón’s father, Gilberto Rodríguez Orejuela, and his father’s brother led the crime group. Both pleaded guilty to conspiracy to launder drug money in the U.S. in 2006.

In 2002, Colombian media reported that Rodríguez Mondragón was arrested after police found heroin in his Bogotá apartment. The prosecutor’s office declined to share a copy of the case file, but official online records show Rodríguez Mondragón was convicted and served just over two years on a drug-related charge before being released in June 2005 under a “conditional suspension” of his sentence.

Rodríguez Mondragón told reporters that the episode was “a setup” aimed at putting his family “in the public spotlight.”

After serving his sentence, Rodríguez Mondragón settled in Roldanillo, a town 130 kilometers north of Cali. There, Fernapez was set up in a house in a quiet area near a mountainside. Two neighbors said they remember a strong and constant fish smell emanating from the house.

“They worked behind closed doors,” one woman said.

The neighbors said they were also struck by the fact that there were no Colombian workers in the company — only two people the neighbors identified as Chinese.

A spreadsheet of seizures made by Bogotá’s Environment Secretariat, obtained by reporters through freedom of information requests, showed that the shark fins seized in Bogotá came originally from Buenaventura, a port city over three hours from Roldanillo by car.

Official data shows that Buenaventura is a hub for the illegal trade in shark fins. In most of the 23 seizures of shark fins and shark meat made between the ban in March 2021 and July 2023, the parts had originated in Buenaventura or the nearby port city of Tumaco, according to official data.

Fernapez’s permit from Colombia’s National Aquaculture and Fisheries Authority, known by its Spanish acronym AUNAP, said the company had a storage warehouse in Roldanillo and that it was authorized — before the ban — to market different species of sharks.

The shipment remained with Rodríguez Mondragón’s company, Fernapez, in Roldanillo for three and a half weeks before it was sent to Bogotá.

The company set to receive the cargo in Hong Kong was Ho’S Import & Export Limited, which has been the main buyer of Fernapez’s exports, according to Colombian customs data. A reporter who visited the address where Ho’S Import & Export is registered found a locked office in a 15-story building in a remote industrial area. Employees at a neighboring office said it was rarely open.

Ho’S Import & Export did not respond to questions sent by reporters.

Customs data shows that 36 out of 53 total fish bladder shipments from Fernapez to Ho’S Import & Export from 2019 to 2021 were valued at $30,000, despite the fact that their weights varied considerably and their shipping codes indicated they were the same product.

Juan Ricardo Ortega, the former director of Colombia’s National Tax and Customs Directorate, told reporters that such “numbers are never so absolute.”

Rodríguez Mondragón said the prices were the same despite different weights because the value of the bladders varies depending on the species of fish. For example, “croaker is more expensive than hake and cachama,” he said in an email.

Rodríguez Mondragón appears to have closed up shop in Roldanillo soon after the shark fin shipment was seized in Bogotá. In November 2021 –– two months after the seizure –– he sold the property where Fernapez operated for 68 million Colombian pesos (about $15,500).

Rodríguez Mondragón said the property was sold because the company went broke “as a result of the problem.”

Sophisticated Processing

Over half the fins in the seized shipment were from the silky shark species, classified as “vulnerable,” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Other fins came from the scalloped hammerhead shark, classified as in “critical danger,” and the pelagic thresher shark, bull shark, and tiger shark, which are all classified as “threatened.”

All these species are protected under an international convention known as CITES, which aims to stop trade in a species from threatening their survival. Colombia, which signed on to the agreement in 1981, banned the fishing and trade of sharks and their parts in March 2021.

Such shark fins are used in Hong Kong to make soups that can cost up to $200 a bowl. This results in a lucrative industry: Conservationists estimate that, globally, the trade in shark fins alone may earn as much as $500 million a year.

But the fins must first be peeled, entailing a complex procedure that involves the use of chemicals and specific know-how which experts say is found almost exclusively in China.

Because processed shark fins can fetch a higher price, that means greater profits for traffickers if they can process them themselves. But doing a poor job can cause the fin to lose its value, meaning it is unusual to find a shipment of processed fins in Latin America.

Experts said that the fact that the fins in the seized shipment had been processed before export showed that wildlife traffickers appeared to be starting to import this knowledge from Asia.

The biologist Diego Cardeñosa said that he and other experts believed that there must be an “organized” effort behind Chinese workers “coming to these countries to teach people how to do that processing," though there was still not enough evidence to say for certain.

After reviewing photos of the seizure, Stanley Shea, marine programme director at Bloom Association, a Hong Kong-based NGO dedicated to ocean conservation, said that the shark fins appeared to be “ready for the market.”

“They didn’t do it perfectly, but they know how to do it,” he said.

A wider distribution of processing techniques could make the fight against wildlife trafficking more complex by making it harder to identify the species of sharks without DNA tests, Alicia Kuroiwa, director of habitats and threatened species at Oceana Perú, said.

“If we start to have peeled fins, we have a problem, because identification becomes complicated,” she said.