Reported by

Something makes Lance Zane Ricotta stand out as a private plane broker in the U.S.: the frequency with which his aircraft end up in drug trafficking incidents.

It’s not unusual for private U.S. planes to be used to move narcotics. American aircraft are easy to spot because they all have tail numbers beginning with the letter N, and U.S. planes are coveted by traffickers because they’re less likely to be targeted for inspection or shot down by foreign authorities.

But Steve Tochterman, a former Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) special agent, told OCCRP it was rare for a U.S. plane broker to have more than one aircraft end up in drug-related incidents. A one-off likely meant the seller was unlucky. “But then you run into Lance Ricotta and it’s over and over again. You’re in a different ballgame,” Tochterman said.

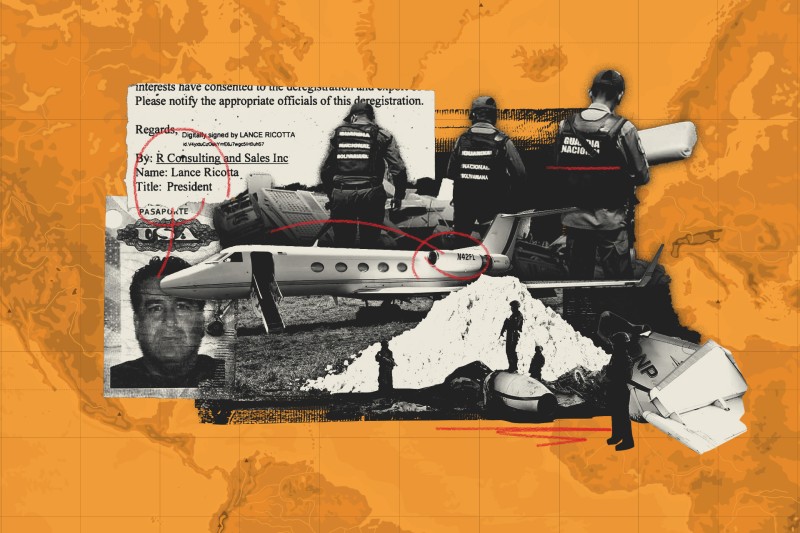

It’s difficult to confirm exactly how many planes Ricotta’s sold, and to whom. The FAA relies on sellers or buyers to self-report aircraft sales and changes in ownership, and even then there is not much historical data: the FAA’s registry can only be searched via a plane’s current owner. But after filing Freedom of Information requests with the FAA and scouring open-source aircraft websites, OCCRP confirmed at least 30 planes sold since 2014 by companies Ricotta controlled either directly or via his girlfriend, who was the on-paper CEO of two firms called R Consulting & Sales Inc that Ricotta appeared to run behind the scenes.

Of the 30 sales identified by reporters, 11 — more than one third — were either seized, investigated, or found abroad in suspected or confirmed drug cases, often immediately after the sale, an OCCRP investigation has found.

Most of those incidents took place in the last six years, including:

April 13, 2022: Suspected cocaine traffickers abandon a private jet in the remote grasslands of Venezuela.

October 29, 2023: Honduran authorities find a second jet burnt and destroyed in the jungle after a suspected drug run.

December 22, 2023: A third goes missing while sightseeing over the Caribbean Sea — only to turn up in Ghana with traces of cocaine inside.

The cases appeared to be unrelated. But they had all been sold to their owners by Ricotta.

In another case, the buyer was the nephew of a former business associate of Ricotta’s, Christian Eduardo Esquino Núñez (known as Ed Núñez), who later told U.S. investigators he procured aircraft for a Mexican cartel. Núñez’s nephew even admitted using drug cartel money to pay for the plane sold by R Consulting via an intermediary.

When contacted by OCCRP, Ricotta did not deny that some of his former planes ended up in drug trafficking incidents, but said that they were a small percentage of the “hundreds” he said he had sold over the years.

Leaked Records Led to Planes Sold by Ricotta’s Company

He also pointed out his lack of legal liability.

“Are you responsible if you sold a car to a guy and he goes and robs a bank?” he asked. (He declined to answer detailed questions about specific sales.)

He’s right – jet brokers are under no legal obligation to vet whether the buyer is a criminal or a terrorist, and there’s no need for a license or certification to buy and sell aircraft. OCCRP found no evidence Ricotta knew the purchase of one of the planes he’d sold was financed with cartel funds, nor that he was aware that his customers planned to use the planes they bought from him to traffic drugs.

But in a sprawling industry that experts describe as a Wild West, some providers, including Ricotta, have carved out a lucrative niche for themselves by supplying U.S.-registered aircraft to anonymous customers, many of them abroad. Selling to unknown clients means they can operate with “willful blindness,” experts said, ignoring issues that would be cause for concern in sectors like banking, governed by explicit know-your-customer rules.

“There’s more regulation on car dealers, and you have to have a license to even sell yachts, but not airplanes,” Scott Weigman, a former Homeland Security Investigations special agent, told OCCRP. “It’s amazingly unregulated.”

Ricotta did not respond to specific questions about whether he knew the identities of his clients or how they planned to use the aircraft they purchased from him.

U.S. law does not allow non-citizens to register as the owner of an airplane, but there are loopholes that let them do so in practice, including setting up U.S. shell companies or financial trusts through which they can own the planes. Of the 11 planes sold by Ricotta that ended up in cases linked to suspected drug trafficking, three were sold to anonymous trusts and four to anonymously owned shell companies.

This workaround, combined with how easy it is to register an aircraft in the U.S. — all that’s required is sending in a proof of purchase, a single form, and a $5 registration fee to the FAA — creates what experts said was a significant blind spot in U.S. anti-narcotics efforts.

“[T]o track ownership is going to be very difficult if [buyers] undertook any measures to try to remain anonymous, which they can [do] very easily,” said Michael Vigil, who before retiring headed international operations for the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

The patchy system for registering and tracking aircraft owners has contributed to the number of U.S. planes being used by foreign criminal groups, according to Sen. Charles Grassley, who was previously the co-chair of the Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control. He authored a scathing security assessment last year on the FAA’s “overindulgent registration practices.” The door was left open, he said, for transnational crime organizations to register planes in large numbers.

The FAA told OCCRP that it has “a robust relationship” with its foreign partners to identify any U.S.-registered aircraft that foreign nationals may own, but did not respond to questions about specific planes or documents.

Meanwhile, sellers like Ricotta remain under no legal requirement to know the identity of their customer.

An Alleged Drug Trafficker’s ‘Right-Hand Man’

Ricotta, 54, grew up near San Diego, in the midst of both law enforcement and the aircraft industry. His father was a San Diego deputy sheriff and DEA agent who flew air guard for two U.S. presidents.

Ricotta got his start refueling airplanes at an airport north of San Diego as a teenager in the late 1980s. Later, he obtained his pilot license and began flying aircraft around on behalf of local brokers, he told a podcast host earlier this year.

“I would do anything I could, fly anywhere,” he said. “I learned a lot about the buying and selling of aircraft, and one thing led to another.”

Since then, his clients have included Hollywood stars such as Sylvester Stallone and Goldie Hawn, production companies like the Discovery Channel, and a five-star Las Vegas hotel.

But Ricotta’s client list wasn’t just A-listers: He also sold planes to shell-firms and anonymous trusts. While a legal and routine practice in the industry, selling to such ownership structures means the buyers’ identities and their source of funds are difficult to trace. In multiple instances, planes Ricotta sold this way ended up being used for drug trafficking.

One such sale, in March 2020, was to an apparent intermediary that immediately sold a Hawker Siddeley jet on to Wyoming shell firm TWA International Inc. The intermediary was an anonymously owned Delaware company, but TWA was owned by Texas-based aircraft dealer Carlos Rocha Villaurrutia – the nephew of Ricotta’s former business associate Núñez. Ricotta did not respond to specific questions about whether he knew Rocha’s TWA was the final client in the sale.

Records show TWA purchased the jet from the intermediary the same day the intermediary had purchased the plane from the Nevada company registered to Ricotta’s girlfriend that Ricotta himself appears to have controlled. Her company, R Consulting, had flown the jet to Mexico a month prior to the sale.

Signs Ricotta Ran R Consulting

Court records reviewed by reporters suggest the deal was financed with drug money. In a 2021 affidavit, a DEA agent said Rocha had provided a list of tail numbers of planes that “were purchased with the proceeds of the drug funds received from the [Jalisco New Generation Cartel]” – it included the Hawker Siddeley, according to the sales bill for the transaction reviewed by OCCRP.

In the same affidavit, the DEA agent said Núñez admitted that he had been buying planes on behalf of the Jalisco Cartel, according to the agent’s summary of the conversation. The affidavit indicates Núñez and Rocha had been working together, and OCCRP found Núñez was acting as TWA’s sales manager around the time of the Hawker Siddeley deal, according to sales documents.

Núñez, a politically connected Mexican businessman who has been a key figure in U.S. aircraft brokerage for decades, was Ricotta’s former business associate.

Ricotta and Núñez were imprisoned in the U.S. in the 2000s for conspiracy to commit fraud involving aircraft, which involved importing planes from Mexico and forging the logbooks used to record the planes’ flight and maintenance history. The scheme unraveled after the engine of one of the planes failed during an attempted landing, nearly killing its new owner. The pair pleaded guilty, and investigating agents in the case concluded that Ricotta had been the “right-hand man” to Núñez in the operation.

Núñez was released from prison in 2007 and ended up back in Mexico, from where U.S. investigators suspected he continued to illegally buy American planes using proxies, according to facts presented by prosecutors in a forfeiture case brought by the U.S. government against one of his planes. Since 1984, Núñez has been identified in connection with approximately 75 DEA investigations for allegedly using aircraft to traffic drugs and launder money, according to an affidavit from the case. (The affidavit did not specify the outcome of the 75 investigations.)

Less than six months after Rocha’s TWA purchased the Hawker Siddeley, it was seized by Mexican authorities when it was found to be carrying narcotics, forged paperwork and a firearm, according to Mexican prosecutors in an official written notification, a type of online subpoena.

And in early 2021, Rocha was indicted by U.S. prosecutors for using TWA and other companies to supply drug traffickers with aircraft. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 12 years in prison. The court documents from that case did not mention the Hawker Siddeley sold by R Consulting.

There’s no evidence Ricotta knew Rocha was the end buyer or that he would pay for the plane with drug money. But former FAA administrator Tochterman said the way transactions like this are structured — using anonymous companies and via intermediaries — is a sign that such sales could be questionable.

“[Normally] you don’t see these types of transactions…You don’t see people who have been convicted of crimes, back to back, working with legitimate people,” he said.

Ricotta did not respond to specific questions about the Hawker Siddeley sale. OCCRP sent questions to Rocha and his companies, but did not receive a response. Reporters were unable to reach Núñez for comment.

The most recent case of a Ricotta-sold plane turning up in a drug-related incident involved another shell company, and is an illustration of how easily a mystery owner can obtain a U.S. aircraft that quickly ends up in the wrong hands.

This March, a Gulfstream II turned up destroyed on a clandestine airstrip in the rainforests of southern Belize.

Drug traffickers had removed any identifying information and set the plane ablaze.

Still, the torched jet made the news, and attracted the attention of drug trade plane-watchers. One of them — Jesus D. Romero, a retired U.S. Navy lieutenant commander who also served as tactical analysis chief of the Joint Interagency Task Force — identified the plane as N30WR.

Romero said he was able to hone it down based on details such as the paintwork and hush kits.

“It was a perfect match,” he told OCCRP.

The last available flight transponder data shows that N30WR had left California for Mexico five weeks earlier, flying toward the state of Hidalgo.

The plane was sold by Lance Ricotta.

The pattern of American aircraft ending up in drug trafficking incidents raises questions over weak aviation regulations and enforcement in the U.S., experts said.

While the FAA approves the registrations and maintains a database of civil aircraft registrations, it largely relies on self-reported data, and doesn’t have the resources to check up on all the registrations it receives. It does have a small investigative unit, which can assist investigations by law enforcement agencies upon request, but does not refer cases for prosecution.

Experts criticized this apparently toothless approach to monitoring who is buying U.S. planes, and to taking action against buyers and sellers when American aircraft end up in the wrong hands.

“If you're wondering why they keep doing it, [it’s] because they face no consequences from the FAA,” Tochterman, the former FAA special agent, told OCCRP. “The FAA has no procedure or mechanism to deny you the authority to register an aircraft.”

To the ire of some in the trenches, the lack of any real action at the FAA enables and emboldens the sale of aircraft that end up in the hands of traffickers.

“In order to commit the crime, you can't commit it by yourself and your buddy, right? That's Hollywood,” said Romero, the retired U.S. Navy lieutenant commander. “You need a complete system that allows it to happen. You need the FAA.”

The FAA said it works “closely with law enforcement agencies daily to address cases of suspected fraudulent aircraft ownership” and has “a robust relationship with our foreign partners to identify US-registered aircraft that foreign nationals may own.”

‘No Way to Find a Responsible Party’

Small planes and private jets have been indispensable tools for organized crime groups engaged in large-scale drug smuggling for at least half a century. In particular, business jets like the Gulfstream are prized for their ability to fly long distances without needing to refuel, and for the large amounts of cargo they can carry.

A Court Case Could Set a Precedent for Plane-Registration Accountability

Although experts have for years warned about the role that U.S. aircraft play in the drug trade, jet providers and brokers who are considered key facilitators have largely escaped punishment. The 2020 conviction of Debra Lynn Mercer-Erwin is a rare exception.

While American jets are the most sought-after, there are scant statistics on the number of U.S.-registered aircraft used in drug trafficking since the trade is clandestine by nature, but experts agree that cartels have for years been able to obtain U.S. jets with ease, and use them to move large volumes of cocaine. Typically, a trafficking group will destroy a plane when it’s no longer needed, sometimes after only one or two flights, to avoid it being tracked and to destroy the evidence.

A report by Mexico’s Secretariat of National Defense found that US-registered aircraft accounted for more than half of all unauthorized flights through Mexico. A confidential U.S. Embassy memo identified 55 that had been flagged for suspicious activity in Mexico between 2019 and mid-2020.

The use of shell companies and trusts to buy aircraft makes it nearly impossible to find out who owns the planes that have been flagged as suspicious. This, combined with the FAA’s rudimentary monitoring and investigative capacity, means there is limited attention to ensuring that a U.S. registered plane does not fall into the wrong hands. In a 2017 investigation, the Boston Globe found that over 50,000 of the over 300,000 planes on license with the FAA at the time were registered using secrecy tactics, like trusts.

"Our issue is keeping planes from crashing into each other," former FAA Associate Administrator George Donohue told OCCRP, noting the agency historically has left investigating registration matters to law enforcement. “We're a civil aviation authority; we don't have investigative powers.”

The same concern was raised in a 2020 report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the watchdog on US government spending. The office said the FAA’s continued failure to verify the identities of airplane owners left the U.S. plane registration system wide open to abuse by criminal networks.

“We found the FAA generally relies on self-certification and doesn’t verify key information such as applicant identity or aircraft ownership,” the report concluded. “Shell company or limited liability company ownership can also make it difficult to determine who ultimately owns an aircraft.”

At the GAO’s suggestion, the FAA began collecting limited ownership data in 2022 for shell companies, asking for the names of foreign company owners. But it stopped short of implementing broader transparency measures, including trying to track the true owners of all aircraft.

And that’s where the rollback of the U.S. Corporate Transparency Act comes in. The law that took effect last year required disclosure about an aircraft’s true owner, putting that information at the fingertips of any law enforcement looking for cartel purchases of aircraft. Soon after taking office, the Trump administration rolled it back, lifting disclosure for U.S. citizens.

The Trump administration is “undoing the enforcement of Congress's Corporate Transparency Act that will let you know who's behind the shell corporation that owns the plane,” said Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, a Rhode Island Democrat and current co-chair on the Senate narcotics caucus. He added, “it is a distinct public safety concern.”

The Trump administration has weakened an important regulatory tool, suggested Gary Kalman, executive director of Transparency International’s U.S. office.

“The gap between ethical responsibility and legal obligation in this particular area is quite large. This is the exact same problem we had with real estate,” said Kalman, whose group advocates greater reporting requirements for true owners of shell companies and trusts.

Attempts to further empower the FAA on ownership transparency have met with resistance. Private aircraft are typically owned by wealthy individuals who prefer discretion and anonymity. Corporations and the U.S. military have also pushed back against public aircraft tracking efforts, saying it would undermine corporate security and add bureaucracy.

In a roll back on transparency efforts, this March the FAA began allowing aircraft owners to request that their information be kept private. It is currently weighing up whether to keep ownership data confidential by default.

Meanwhile, the FAA in early June closed an extended comment period as it implements a little-known congressional mandate from 2004 that allows aircraft owners to keep their names and addresses out of the public registry. It was aimed at protecting the privacy of the wealthy and famous, but many respondents warned it will embolden bad actors.

The status quo has benefitted the federal government: Following the 9-11 terror attacks, the CIA chartered planes registered to shell companies for rendition flights that brought suspected terrorists to Guantanamo Bay in Cuba and elsewhere.

In around 2004 or 2005, the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) began a controversial program called Operation Mayan Jaguar. The agency used shell companies to sell US aircraft to unknowing drug traffickers in order to gather intelligence. Mayan Jaguar ended in approximately 2008, in part because ICE and the DEA got into a turf battle over the program.

But without the ability to know who owns a plane, experts say it is nearly impossible to crack down on their misuse.

"The system knows that, if you do it all this way, there is no way to find a responsible party,” says Romero.

“It’s very, very difficult and time consuming to get access to all that information,” said Tochterman, the former FAA special agent who, together with Romero, wrote about their experience uncovering the Mercer-Erwin network in the book “Final Flight: Queen of Air.” “When the transaction [sale] is completed outside the United States, it’s almost impossible.”

Misha Gagarin contributed reporting.