When Valery Amelchenko agreed to talk, a reporter from OCCRP’s Russian partner, Novaya Gazeta, was eager to listen.

The gaunt, unassuming 61-year-old isn’t a well-known figure. But he had worked for Yevgeny Prigozhin, the Russian oligarch sometimes known as “Putin’s chef” because his businesses cater the president’s dinners with foreign guests.

Prigozhin’s profile has risen in the last few years. He has been sanctioned and indicted by the United States for funding the Internet Research Agency, the troll farm accused of meddling in the 2016 presidential election.

He is also believed to be behind Wagner, a private paramilitary group accused of fighting in Syria, eastern Ukraine, and other places on behalf of the Russian government. Three Russian reporters for the Dossier Center were murdered this summer while reporting on Wagner in the Central African Republic.

This was a man reporters wanted to know more about.

And Amelchenko did not disappoint, sitting down with a Novaya Gazeta reporter last February to talk about his years working for the oligarch’s security team.

In long interviews over several months, he described a litany of dirty and illegal tactics directed at Prigozhin’s and Putin’s enemies: harassment and spying, poisonings, the murder of an independent blogger, shady operations in Kyiv and eastern Ukraine, and even a trip to Syria that involved testing poison on unsuspecting mercenaries.

(Read the Syria chapter of Amelchenko’s story.)

Valery Amelchenko. (Photo: VKontakte) Reporters found independent confirmation for much of what Amelchenko said, and they never caught him telling a lie. And though he never claimed to have gotten orders directly from Prigozhin, his stories shed light on the cruel and sometimes extreme way the oligarch’s security team operated. (Prigozhin did not respond to a request for comment.)

Valery Amelchenko. (Photo: VKontakte) Reporters found independent confirmation for much of what Amelchenko said, and they never caught him telling a lie. And though he never claimed to have gotten orders directly from Prigozhin, his stories shed light on the cruel and sometimes extreme way the oligarch’s security team operated. (Prigozhin did not respond to a request for comment.)

Amelchenko then became part of the story himself. On Oct. 2, about an hour and a half after meeting with a reporter one last time, he disappeared in an incident that looked very much like a kidnapping.

Then, shortly after reporters started asking questions of Prigozhin’s security staff, the paper received threatening messages: A funeral wreath showed up at its offices bearing the reporter’s photo, followed by a sheep’s head in a basket.

Nevertheless, Novaya Gazeta published a story using the material Amelchenko had provided.

Then, three weeks later, he reappeared at a police station. But now his position had changed entirely. While confirming that his interviews had taken place as described, he now claimed that the whole affair — including the content of his conversations, his being followed by two men, and his disappearance — had been staged by the reporter.

“Not Too Dirty”

A Man With Little Background

Valery Amelchenko did not offer much about his past.

The earliest reliable information about him dates to 1999, when, according to police records, he took part in a robbery in St. Petersburg and hijacked the victim’s car.

He was sentenced to a seven-year imprisonment in Perm, and was released on parole in 2004. It’s unclear what he did for the next eight years before landing in Prigozhin’s orbit.

Though Amelchenko never received orders from Prigozhin himself, the command structure he described clearly involved the oligarch’s senior associates.

He said that the man who brought him on was Andrey Mikhailov, who had worked for Prigozhin in 2012 and 2013. For a while, Mikhailov was the man Amelchenko reported to, visiting him at his office in a St. Petersburg business center.

In an interview, Mikhailov confirmed that he met and hired Amelchenko. At the time, Mikhailov said, he himself worked under a man named Yevgeny Gulyaev, a former Interior Ministry operative who headed Prigozhin’s security detail.

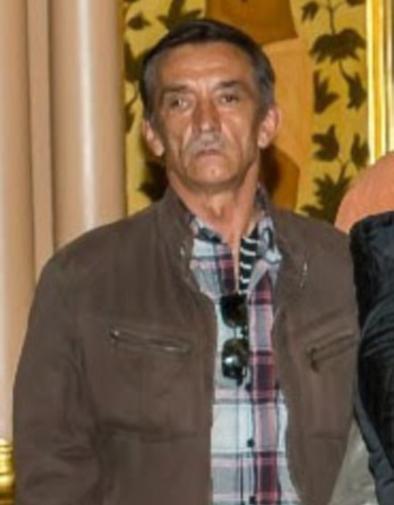

Andrey Mikhailov. (Photo: Denis Korotkov)

Andrey Mikhailov. (Photo: Denis Korotkov)

Mikhailov was an important figure, having played an active role in organizing Prigozhin’s media outlets and his infamous “troll factory.” He was an aggressive advocate for Putin’s Russia, and his media network served as an attack dog against the president’s — or Prighozhin’s — critics. His publications frequently ran aggressive screeds against opposition writers and independent outlets.

Amelchenko said that the work did while under Mikhailov, consisting mostly of surveilling people and organizations, was “not too dirty.”

For example, he remembered one trip to Moscow during which he surveilled a young woman at the premises of Novaya Gazeta. This would likely have been Maria Kuprashevich, who had been hired by Prigozhin’s people to work in the newspaper’s advertising department, enabling her to collect information about its staff and publications.

Amelchenko also recalled taking part in a staged traffic accident where a man was hired as a “victim” to fall under the car of a businesswoman who was embroiled in a real estate dispute with Prigozhin at the time.

The woman, Yelena Cherevko, told Sobesednik in a 2016 interview that the dispute arose over a building in St. Petersburg. “A drunken homeless man was thrown under my car, as though I had hit him,” she said.

Mikhailov confirmed that this incident really had been a set-up, and was even recorded on video. He showed reporters the recording, taken on Feb. 7, 2013, in which Amelchenko can be seen “assisting” the man who was allegedly run over by Cherevko’s car.

Educating a Blogger

Amelchenko’s work gradually grew more serious. In fall 2013, as Mikhailov recalled, his subordinate visited the city of Sochi with a friend in order to have “a tough talk ” with a local blogger who had written “something offensive” about Putin.

According to Amelchenko, the blogger sold car parts and was lured to a meeting under the pretext of a business deal. After the confrontation, Amelchenko said, the blogger was left with a broken collarbone and soon ceased all publication under his username.

“I’m not a doctor, not a surgeon, and not a traumatologist ... but he’s alive and well,” said Amelchenko. “Well, I don’t know about his health; no one ever showed me his clinical report. ... And that was that. Mikhailov was satisfied.”

Mikhailov also provided the blogger’s username, huipster, and shared photos taken during his team’s undercover surveillance of their target.

A surveillance photo of Antion Grishchenko, also known as ‘huipster,’ taken by Mikhailov’s team. The photo has been edited to protect his privacy. (Photo: Andrey Mikhailov)

A surveillance photo of Antion Grishchenko, also known as ‘huipster,’ taken by Mikhailov’s team. The photo has been edited to protect his privacy. (Photo: Andrey Mikhailov)

Traces of huipster — whose real name is Anton Grishchenko — can easily be found online. In 2013, he promoted his video blog on YouTube, in which he mostly addressed local problems in Sochi. Shortly before his meeting with Amelchenko and his friend, Grishchenko had indeed tweeted a crude caricature of Putin by a French satirical newspaper. The blogger’s social media accounts were deleted shortly after the encounter.

Grishchenko refused to discuss the events of 2013.

The friend Amelchenko went to Sochi with was a man named Vladimir Gladienko. When reporters asked him about the incident, Gladienko said he remembered flying to Sochi with Amelchenko, but claimed to know nothing about the blogger.

Ukrainian Transit

Amelchenko’s work with Mikhailov ended abruptly in late 2013 when the more senior man was fired. Amelchenko says that he learned this from other associates while attending the Maidan protests in Kyiv, where he said he spent some time “alone” in late 2013 and early 2014.

Asked whether he had been on the Maidan on personal business or on assignment, Amelchenko said, “I’m not rich enough to travel there on my own initiative.” He did not say more about his adventure during the Ukrainian revolution that ousted pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych.

According to Mikhailov, however, Amelchenko had gone to Kyiv to pay for the organization of “demonstrations.” This is a possible reference to the groups of young men who shouted slogans and attacked anti-government protesters during the uprising.

Mikhailov’s End

Three years after Mikhailov stopped working for Prigozhin, he allegedly fell victim to Prigozhin’s people himself.

In May 2017, Mikhailov notified the police that he had been abducted, taken to the outskirts of St. Petersburg, beaten, and forced to sign a promissory note for over three million rubles, as well as to hand over important company documents.

The group that attacked him was led by a man he knew — a person who reportedly worked for Prigozhin.

After Mikhailov’s dismissal, Amelchenko was then contacted by someone he didn’t name (though Mikhailov says this may have been Gulyaev, the head of Prigozhin’s security detail). Afterwards, Amelchenko’s regular contact was another of Prigozhin’s men named Andrei Pichushkin.

From 2014 to 2016 Amelchenko worked mostly in Ukraine, including in the breakaway Luhansk People’s Republic. He spoke little about this phase of his work, though he did allude to the use of a 9-millimeter PB “silencer pistol” in a “talk” with a well-known person in Luhansk he called “Plotnitsky’s right hand.”

The episode, he said, took place in a stairwell of a nine-story apartment block. And his description closely resembles the murder of Dmitry Karagaev, an assistant to Ihor Plotnitsky, then the leader of the Luhansk People’s Republic. Karagaev’s corpse was found with gunshot wounds on the second floor of a stairwell in a Luhansk apartment building on March 16, 2016.

A Dangerous Bouquet

Novaya Gazeta reporters first learned Amelchenko’s name while investigating a poisoning incident that would end up shedding light on some of his work.

This concerned an attack on the husband of Lyubov Sobol, a lawyer who works for Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation. Navalny is a longtime Putin critic and opposition leader.

On the evening of Nov. 25, 2016, Sobol’s husband Sergey Mokhov, a sociologist and magazine publisher, was on his way home. A young man with a beard stood at the entrance of his Moscow apartment block, holding a bouquet of flowers.

The Attack in Amelchenko’s Words

“[Mokhov] used to go to some gym in the evenings. … [Simonov] followed him for several days ... he said he had bought a bouquet of flowers and waited for him outside his house. His task … was simply to seriously scare the guy. He pricked him with some medicine. ... [Mokhov] came up and said [to Simonov], are you waiting [for someone]. ... [Simonov responded] ‘I am. I’ve been waiting. Nothing personal.’ Then he pricked him, threw the flowers away, and left.”

When Mokhov passed by, he felt a sharp sting in his leg, after which he started to convulse and fell to the ground. He was hospitalized and eventually recovered.

According to Mokhov’s lawyer, Sergey Badamshin, doctors theorized that a drug, perhaps an antipsychotic agent, had been administered.

Mokhov and his wife have two theories about the attack. Mokhov said the attack could have been related to his work, as he had previously published articles about criminals operating in the Russian funeral services business.

Sobol, on the other hand, suggested that the poisoning could have been an act of revenge by Prigozhin. At the time, much of her work at the Anti-Corruption Foundation focused on his activities. In particular, she had investigated the granting of multi-billion-dollar state contracts to companies affiliated with him.

Navalny, the Anti-Corruption Foundation’s director, echoes Sobol’s view. While he says he “can’t be 100 percent sure that Prigozhin and his people are behind the attack,” he considers this to be the most likely explanation.

The attacker was recorded by a surveillance camera, and images clearly showing the face of the “unknown man with the bouquet” quickly appeared on the internet. But his identity would remain a mystery for almost two years.

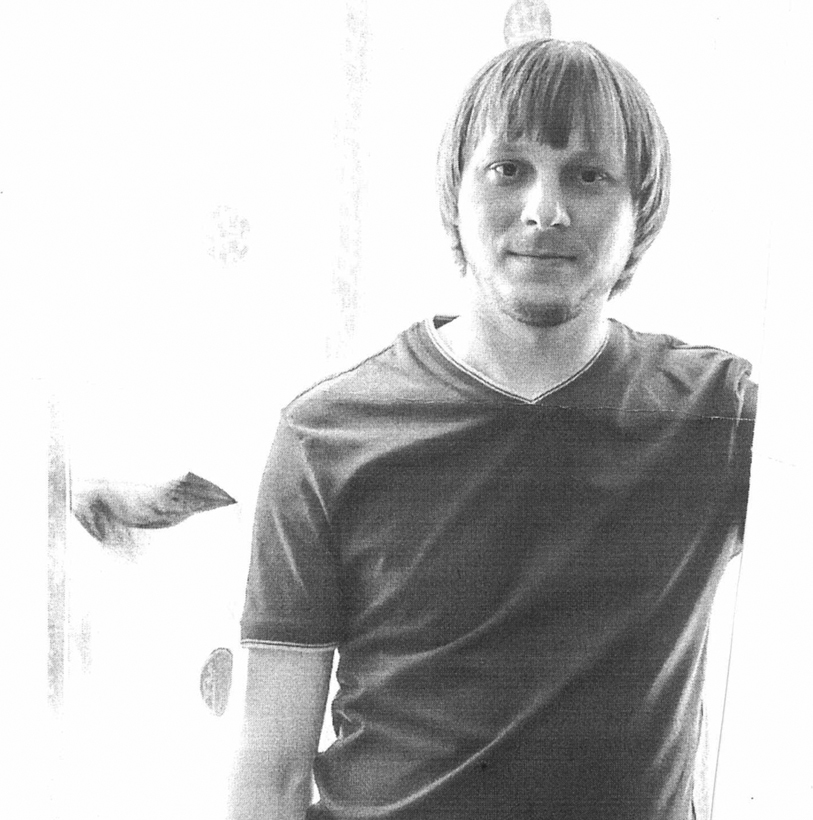

A still from a video showing Sergey Mokhov’s attacker. (Photo: Life Novosti)

A still from a video showing Sergey Mokhov’s attacker. (Photo: Life Novosti)

Earlier this year, a source insisting on anonymity approached reporters and identified the man as an Oleg Simonov, originally from the Amur region, who had recently lived in St. Petersburg. A social media search uncovered a man by that name with a September 1982 birthdate who had worked for several pharmaceutical companies.

Oleg Simonov. (Photo: Valery Amelchenko) When reporters contacted Simonov’s wife and showed her the surveillance video, she confirmed that the man depicted was her husband, but asked reporters not to use her name.

Oleg Simonov. (Photo: Valery Amelchenko) When reporters contacted Simonov’s wife and showed her the surveillance video, she confirmed that the man depicted was her husband, but asked reporters not to use her name.

She said that Simonov’s studies had included pharmacology and that he worked at a pharmacy. She also said that he was no longer living.

Looking back at their marriage, Simonov’s widow said that her husband had clearly been up to something suspicious.

She recalled two separate incidents when he left St. Petersburg “on business” without explaining exactly why.

The first was a trip to Moscow in 2016, shortly after they met.

Then, in February 2017, shortly after their wedding, Simonov left again, this time for a month. Though he again told his wife he was going to Moscow, Amelchenko would later tell reporters that this was when he and Simonov were in Syria. (See: Prigozhin's Men in Syria)

Simonov’s wife said that it was only after his death that she realized that she “didn’t know the person with whom [she] lived.” At his funeral, the widow saw some of his acquaintances for the first time. She later recognized one of them from a photo showed to her by journalists. It was Amelchenko.

According to Amelchenko, who filled in the details of the story later, Simonov had died six months to the day after the poison attack under what he described as unexplained circumstances. Friends who knew him well said that Simonov rarely drank and never used drugs. Nevertheless, Amelchenko said he had heard Simonov was found dead in a bathtub in his rented St. Petersburg apartment after overdosing.

“Nothing Personal”

Why He Talked

It took a while for reporters to find Amelchenko, but when they did, he agreed to talk.

He did so, he said, because he suspected that people working for Prigozhin could have been involved in the death of Simonov, whom he considered a friend. He thought his alleged killing may have been a punishment for what happened in Syria. (See: Prigozhin's Men in Syria)

Furthermore, he understood that after being approached by journalists, he would no longer be able to continue his covert activities without putting himself at risk.

An agreement along those lines was reached. It spelled out that, if something happened to him, Novaya Gazeta had the right to publish any information he had provided after Oct. 20, 2018.

Amelchenko said that he and Simonov met through mutual acquaintances, and that the pharmacist had told him he was looking for additional work in late 2015 or early 2016. After he joined the team, a new emphasis was placed on conducting covert operations involving drugs.

Amelchenko didn’t go into detail about the nature of the substances, saying he had very poor grades in chemistry at school. However, he did describe one of the devices used: the description matched that of a veterinary tranquilizer dart.

He said that he hadn’t played any part in Simonov’s attack on Mokhov and only learned the details from Simonov’s retelling of the event. The aim of the operation, he said, was to scare both Mokhov and his wife, the Anti-Corruption Foundation lawyer.

Another Poisoning

In 2016, Amelchenko recalls, his group headed to Pskov, a town of over 200,000 near the Estonian border.

Amelchenko said the plan was to go to a certain blogger’s house on Fomina Street and inject him with poison. His job was not to attack the blogger himself, but rather to “watch from around the corner.” Simonov was to drive the getaway car.

The attack took place in the morning as the blogger headed to work. Amelchenko could not remember the blogger’s name, but did recall a garage on the property on which an advertisement for a glazier’s workshop and corresponding telephone number were painted.

The blogger, who was about 35 to 50 years old, died soon after being injected. A few days later, Amelchenko phoned the number on the garage to, as he put it, “verify” the result. The blogger’s son answered with the words, “Daddy died.”

But this wasn’t sufficient, and Amelchenko was told to call back another time to find out from the blogger’s relatives where he was buried, go to the cemetery, and photograph the gravestone.

A Google Street View photo of the garage on Fomina Street in Pskov. (Photo: Google)

A Google Street View photo of the garage on Fomina Street in Pskov. (Photo: Google)

In Pskov, reporters located a house on Fomina Street that matched Amelchenko’s description, including the word “glass” written on the garage with a telephone number. An internet search revealed that a blogger named Sergey Tikhonov, who wrote under the pseudonym skobars, had lived there and died of a heart attack nearby on June 29, 2016.

There was no investigation of Tikhonov’s death, but Amelchenko’s description is meticulous. He described exactly what Tikhonov’s house looked like, pointed out details not visible on Google Maps or the Russian service Yandex, recalled which car Tikhonov used to drive to work, and recounted the blogger’s place of burial.

The Disappearance

Amelchenko’s last meeting with reporters took place at the Shokoladnitsa cafe on Malaya Sadovaya street in St. Petersburg on the evening of Oct. 2. He ordered an apple juice.

The interview ended at about 8 p.m. At about 9:22, he phoned the journalist in some distress to say that he was being watched by two men, “a young guy in a white jacket, wearing glasses, about 25. [And] another one with a Panama hat.”

The call was cut off, and repeated calls to his phone were not answered. Over an hour later, a stranger answered Amelchenko’s number.

“I’m a resident of 110 Leninsky [Prospekt],” he said. “I just found a two telephones and a [shoe] on the ground.”

The place where Amelchenko’s phones and shoe were found after his disappearance. (Photo: Denis Korotkov)

The place where Amelchenko’s phones and shoe were found after his disappearance. (Photo: Denis Korotkov)

The man, who lived in the apartment block next to Amelchenko, gave journalists the two phones, which he had found next to a garage near the building, and pointed out the shoe. The phones matched the numbers Amelchenko had used, and the shoe was very similar to those he had worn during the interview.

The police began a search, and the district department of the Investigative Committee in St. Petersburg launched an investigation.

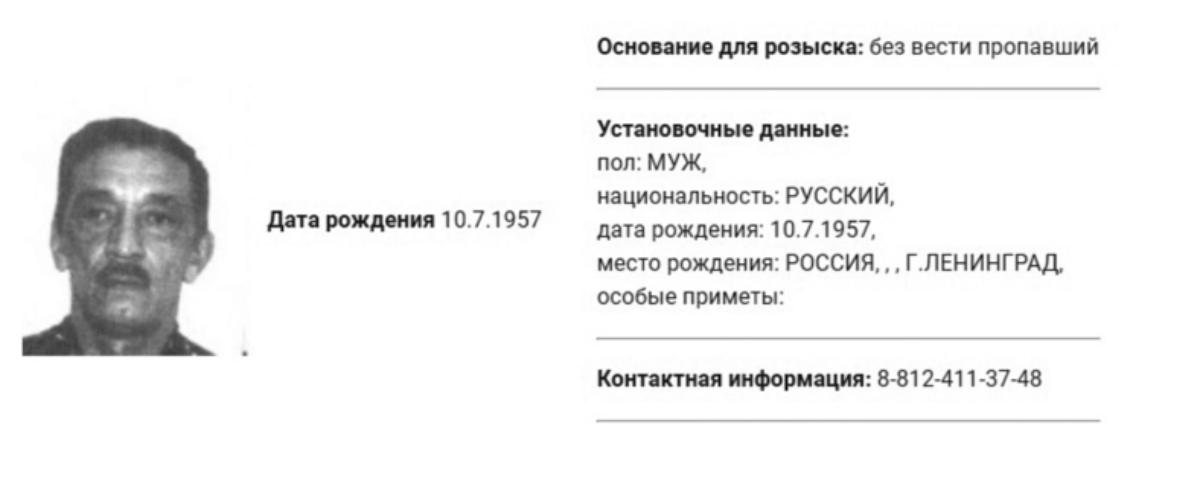

A police notice about Amelchenko’s disappearance. (Photo: St. Petersburg Police) On Oct. 24 — three days after the story that used his material was published — Amelchenko reappeared at a police station and asked them to stop searching for him. And, while he confirmed that his interviews had taken place as described, he now claimed that the whole affair — including the content of his conversations, his being followed by two men, and his disappearance — had been staged by the Novaya Gazeta reporter who had interviewed him.

A police notice about Amelchenko’s disappearance. (Photo: St. Petersburg Police) On Oct. 24 — three days after the story that used his material was published — Amelchenko reappeared at a police station and asked them to stop searching for him. And, while he confirmed that his interviews had taken place as described, he now claimed that the whole affair — including the content of his conversations, his being followed by two men, and his disappearance — had been staged by the Novaya Gazeta reporter who had interviewed him.

Amelchenko has not issued any public statements or denials since.