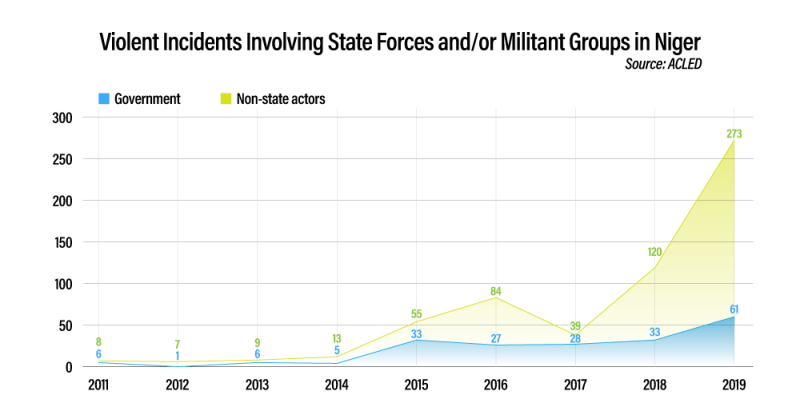

As militant groups spread across the Sahel, the West African nation of Niger went on a U.S.-backed military spending spree that totaled about US$1 billion between 2011 and 2019.

But almost a third of that money was funnelled into inflated international arms deals – seemingly designed to allow corrupt officials and brokers to siphon off government funds, according to a confidential government audit obtained by OCCRP that covers those eight years.

The Inspection Générale des Armées, an independent body that audits the armed forces, found problems with contracts amounting to over $320 million out of the $875 million in military spending it reviewed. The U.S. contributed almost $240 million to Niger’s military budget over the same period.

The Inspection Générale’s auditors said more than 76 billion West African francs had been lost to corruption, which is about $137 million at the current exchange rate.

They discovered that much of the equipment sourced from international firms – including Russian, Ukrainian, and Chinese state-owned defense companies – was significantly overpriced, not actually delivered, or purchased without going through a competitive bidding process.

“The rigged bidding process, fake competition, and inflated pricing in these deals is astounding,” said Andrew Feinstein, a leading arms expert and author of “The Shadow World: Inside the Global Arms Trade.”

The Nigerien authorities are investigating the findings of the audit, which have caused a scandal in the country after some details were reported in the press earlier this year.

The country has become a key ally for the United States in fighting groups like Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and the Islamic State West Africa Province, better known as Boko Haram.

The surge in spending over the last decade helped Niger become one of the most formidable military powers in the region. The country – one of the world’s poorest – bought arms ranging from attack helicopters and fighter jets to armored vehicles and automatic rifles.

In addition to cash it provided to Niger’s military, the U.S. spent $280 million building a massive air base near the ancient trading city of Agadez in the north of the country. The base, which reportedly costs $30 million a year to run, allows U.S. forces to launch drones for both surveillance and air strikes.

American forces are also training Nigerien soldiers and fighting alongside them. In 2017, four U.S. Special Forces officers were killed in an ambush in the country’s frontier with Mali and Burkina Faso, reportedly by fighters associated with the so-called Islamic State.

France and the European Union are also major donors to Niger’s military, which receives further aid through its membership in G5 Sahel, a regional joint military force. The audit report raises the possibility that some of the military aid ended up in the pockets of unscrupulous private individuals and corrupt government officials.

At the center of the network of corruption are two Nigerien businessmen who acted as intermediaries in the deals: the well-known arms dealer Aboubacar Hima, and Aboubacar Charfo, a construction contractor with no previous experience in the defense sector. Auditors allege that the two men rigged bids by using companies under their control to create the illusion of competition for contracts.

Their success points to the opportunities available to a small clique of well-connected insiders with close ties to Niger’s government.

“As far as the audit is concerned, I don't think there'll be any prosecutions,” said Hassane Diallo, head of Niger-based Centre d'Assistance Juridique et d'Action Citoyenne, an anti-corruption group.

“All the economic actors mentioned in the audit belong to the ruling party. They come from the same region as the president.”

Hima's lawyer, Marc Le Bihan, declined to answer reporters' questions, saying that his client could not be reached and adding that he was not being prosecuted in connection with the auditors’ report.

‘Ferocious Style’

Through a handful of companies connected to him, Hima, who goes by the nicknames “Style Féroce” and “Petit Boubé,” handled at least three quarters of all the arms purchases scrutinized by the Inspection Générale. Together the deals were worth $240 million.

It is unclear exactly how Hima, the son of a civil servant at the Ministry of Agriculture, rose to such prominence in Niger’s political and business circles.

One key moment was likely his 2005 marriage to the daughter of former President Ibrahim Bare Maïnassara, who was killed in a 1999 coup. The marriage is likely to have brought him closer to Niger’s political establishment, since the party that Maïnassara once led now “supports the current regime," according to Diallo.

In 2003, Hima set up Imprimerie du Plateau, a printing business that remains active today. By 2010 he had made the leap into the arms business in neighboring Nigeria, where he established companies that would play key roles in the deals auditors scrutinized in his home country.

Most of Hima’s deals were signed under a 2013 national security law that allowed for some of Niger’s defense spending to be carried out in direct negotiations with any company, rather than putting it to public tender. Niger scrapped that law in 2016, replacing it with one requiring a more transparent process. But by that point, much of the damage had been done.

Most of the sales identified in the audit had bypassed oversight bodies within the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Finance whose input was required under the 2013 law. The tenders also did not include key documentation, such as the prices offered by the various bidders.

In one deal facilitated by Hima in 2016, Niger’s Ministry of Defense bought two Mi-171Sh military transport and assault helicopters from Rosoboronexport, Russia’s state-owned defense company. The purchase, which also included maintenance and ammunition, cost Niger 55 million euros, or $54.8 million – an overpayment of about $19.7 million, according to the Inspection Générale. The auditors noted that the prices had been inflated by fraud and corruption.

Russia’s African Arms Deals

Nigerien auditors visited Moscow early this year in search of information about the helicopters and other purchases that had been facilitated by Hima on behalf of Niger’s defense ministry. But the auditors were left in the dark about the terms of the deals. Rosoboronexport refused to provide any information, telling the Nigerien government auditors that the agreements were “confidential.”

“[Rosoboronexport’s] failure to explain the pricing difference on this clandestine deal can only mean one thing: corruption,” Feinstein said. “The Russians clearly colluded with Nigerien officials to sell overpriced arms in a deal that was obviously illegal.”

Rosoboronexport declined to answer OCCRP’s emailed requests for comment. Reached by phone, a representative said: “If you are from the United States, we cannot help you with any answers via email.”

The audit report outlines a series of unorthodox – and in at least one case, blatantly illegal – machinations that allowed Hima to control much of Niger's arms procurement process.

Through his political influence in the defense establishment, a company Hima had founded in neighboring Nigeria, TSI, gained power of attorney on behalf of the Ministry of Defense. This gave him the ability to approve weapons deals and issue end-user certificates, a type of document meant to ensure that weapons sold to one client are not passed on, or resold, to an unauthorized third party.

This is in violation of the Arms Trade Treaty that Niger has signed, which states that end use certificates can only be issued by relevant government ministries,” said Ara Marcen Naval, the head of defense and security advocacy for Transparency International.

The Desert Arms Depot

The corruption of the end-user certificate system in Niger is particularly resonant given the country’s longtime role as an arms trafficking hub. This history dates to the Cold War, when the Soviet Union funneled arms into Niger before shipping them onward to its allies.

The power to issue certificates himself gave Hima the ability to steer government contracts to his own companies, like TSI, or to his partners. It also allowed him to limit the amount of oversight included in the deals’ terms, which removed a crucial safeguard that allows authorities to know who they are selling arms to.

Even before being granted power of attorney, Hima managed to issue Rosoboronexport an end-user certificate on behalf of Niger’s Ministry of Defense in 2018. Hima was on both ends of the deal: While he organized the purchase on behalf of the ministry, his company, TSI, acted as Rosoboronexport’s Niger representative. His company did not appear on the contract.

“The fact that TSI was allowed to represent Rosoboronexport – let alone Niger’s Ministry of Defence – makes this one of the most extreme examples of corruption in the arms trade that I’ve ever come across,” Feinstein said.

Hima used other shady techniques, too. For the helicopter deal and others, companies under his control submitted fake bids to create fictitious and unfair competition, auditors noted.

Another company linked to Hima, Nigeria-registered Brid A Defcon, won a $4.3 million contract to build a specialized hangar for Nigerien President Mahamadou Issoufou’s official plane. Two other companies that submitted bids for the contract — both controlled by Hima — echoed the names of well-known international manufacturers.

One was Motor Sich, which appeared to be an Algerian affiliate of the well-known Ukrainian engine manufacturer. The Ukraine-based Motor Sich told auditors that the company had not made any bids in the deal, said they had no connection to the Algerian entity, and denied any wrongdoing.

However, according to the audit report, it appears that the Algerian Motor Sich affiliate did win other tenders offered by Niger’s government, including a $11.5 million arms supply contract. Hima’s company, Brid A Defcon, acted as Motor Sich’s local agent in Niger in that deal as well.

The other company that submitted a bid for the helicopter deal was Aerodyne Technologies, which used the name of a defunct French aviation company. Though Aerodyne submitted its bid as a company based in the UAE, it appeared to actually be registered in Ukraine, according to the audit.

“As usual, Brid A Defcon has put the companies Motor Sich and Aerodyne Technologies in competition,” auditors noted.

Aerodyne opened emails from OCCRP but did not respond to questions. Brid a Defcon could not be reached for comment.

Among other problematic deals mentioned in the audit, Brid A Defcon also received $4.9 million to outfit the presidential plane with an anti-missile system that was incompatible with the aircraft.

Constructing Arms Deals

Sacks of cement and metal rods are piled on the ground next to a small building in Niamey, Niger’s capital. The compound, a one-story, dirt-colored concrete structure, is the unassuming headquarters of Etablissement Aboubacar Charfo, a construction company named after its owner.

Charfo had no prior experience in the defense sector, and there is no publicly available evidence of him winning any government contracts before President Mahamadou Issoufou came to power in 2011.

Charfo was known as an importer of bathroom tiles and building materials including cement, but he also managed to facilitate nearly $100 million worth of contracts for the government.

He appears to have gotten into the arms trading business through his contacts with the office of Issoufou. Both he and the president hail from the Tahoua Region, where Charfo is said to have strong ties to the ruling Nigerien Party for Democracy and Socialism.

According to publicly available audits of various government bodies carried out by the accounting firm Bureau d'Expertises Comptables in 2017 and 2018, Charfo received several contracts from the presidential administration. One of those was a 2017 contract to furnish the new headquarters of the Inspection Générale des Armées – the same authority that later produced the leaked audit which exposed his corrupt arms deals.

Charfo also received contracts from the president’s office to supply military equipment to the armed forces, including weapons and ammunition, night vision goggles, and a trailer for transporting tanks, according to Bureau d'Expertises Comptables auditors.

The subsequent Inspection Générale audit shows that cost inflation and corrupt practices by Etablissement Aboubacar Charfo and Agacha Technologies, another company linked to Charfo, cost the Ministry of Defense $24.7 million over what it would have paid with fair competition.

The auditors probed five contracts won by Charfo’s two companies between 2014 and 2018. These included a $40 million agreement to purchase armored personnel carriers manufactured by China’s state arms company, NORINCO. Auditors found Charfo had inflated the price, overcharging the government by $8.2 million.

In a 2017 deal, according to the Inspection Générale, Charfo’s Agacha Technologies won a $6.5 million contract to supply 30 buses to the Ministry of Defense. Over half of that total was lost to over-invoicing and wasteful spending, the auditors found.

They also discovered that, like Hima, Charfo manipulated the procurement process to create the impression that he was competing against rival companies.

In reality, the “competing” companies were either controlled directly by Charfo or linked to him. He and his associates benefited from “fake bids and the use of fake competition,” according to the audit.

“The winner of the contract was known in advance,” it read.

Jet-Fuelled Corruption

Charfo and Hima weren't the only businesspeople who appeared to have gotten rich on Niger’s military spending spree by using shell companies to rig bids for arms deals. Several companies in Ukraine, the United Kingdom, and the Czech Republic also appeared to benefit.

The people behind these schemes remain unknown because some of the companies were registered in offshore jurisdictions that enable their owners to remain anonymous. Others were formed as UK limited liability partnerships, which are controlled by other companies, not individuals, and are not obligated to disclose their directors or owners.

At least one of the deals involving these offshore entities appears to have included built-in kickbacks.

In 2012, Ukraine’s state defense company, Ukrspecexport, won a contract to supply Niger with two second-hand SU-25 fighter jets built in 1984. Niger’s Ministry of Defense paid $12.5 million for both aircraft, including $1 million for insurance and delivery and $1.9 million for spare parts. The audit noted that the prices had been inflated and the additional cost of more than 350 spare parts appeared unnecessary and suspicious.

“Adding spare parts to arms contracts is a common technique to build in the cost of kickbacks,” Feinstein said.

The Ukrainian company denied that it made the deals with Niger.

“Ukrspecexport did not make such deliveries and does not have any information on the issues you are asking about,” a representative said in an email.

Despite Ukrspecexport’s denial, international arms trade data collected by the Stockholm International Peace Institute confirms that Niger ordered the two second-hand aircraft, and that they were delivered the following year.

The Nigerien auditors also discovered an addendum to the SU-25 contract that appeared to facilitate a bribe. It stipulated that Stretfield Development, a London-based shell company with unknown owners, was to receive a $2 million commission on the deal in a “maneuver” the auditors described as “collusive” and “contrary to regulations.” The contract specified that the fee would be funded by the Nigerien Ministry of Defense, but paid through another London-based shell company, Halltown Business, which was shut down shortly after the deal was completed.

Details of the suspicious sale did not come as a surprise to Daria Kaleniuk, the head of the Anticorruption Action Centre, a leading Ukrainian advocacy group.

“For many years, Ukrspecexport was known to be a very dodgy company which has a monopoly of trading weapons and army equipment abroad through secret sealed deals,” she said.

The address in London where Halltown was registered belonged to a company formation agent and was used by over 400 other companies. Among these were four firms that were part of the Azerbaijani Laundromat, a vast money-laundering operation that benefitted elites from that country and was previously reported by OCCRP. Halltown’s ownership trail led to a Panamanian company with two Ukrainian directors.

Niger also signed separate maintenance deals with a firm called EST Ukraine. The defense ministry agreed to pay the company $4.3 million for the upkeep of its MI-35s helicopter gunships and the second-hand SU-25 jets it had bought from Ukraine’s state defense company.

But EST Ukraine did not receive the payment. In fact, it was not even formally registered as a company. The company that received the payments — another Ukrainian firm called Espace Soft Trading Limited — was “not a party to the contract.”

That company, formed in 1998, is controlled by Yuri Ivanushchenko, once a member of the Ukrainian parliament and an ally of former president Viktor Yanukovych, who was ousted in a popular uprising in 2014. The auditors listed Ivanushchenko’s company as one of the beneficiaries of the rigged bidding.

“During Yanukovych’s presidency, his close associate Yuri Ivanushchenko was overseeing work of Ukrspecexport and had significant influence over its decisions,” Kaleniuk said.

As with many of the other deals, auditors found that the bids for these maintenance contracts had been rigged. In addition to EST Ukraine, several other foreign shell companies submitted bids, presumably in an effort to create the appearance of competition. One of these was the UAE-registered Aerodyne Technologies, under Aboubacar Hima’s control.

Both Aerodyne and the winning EST Ukraine were run by Gintautis Baraukas, an associate of Hima who appeared to run shell companies on his behalf. Little is known about Barauskas, who used a false nationality while operating a network of shell firms in the UAE.

“This gentleman is not Ukrainian, he is in fact Latvian ... He is involved in several cases that served to extort large sums of money from the State of Niger,” the auditors wrote.

EST Ukraine did not respond to requests for comment.

Shell Companies in Sharjah

The United Arab Emirates is a world-renowned tax haven and the emirate of Sharjah is particularly popular with arms dealers due to its lax financial regulations and opaque aircraft registry, which allows goods to be moved through the airport in relative obscurity. The emirate is home to a host of shell companies that appear to be used to launder the proceeds of arms deals.

The Spoils

A white marble mosque rises beside Hima’s palatial mansion. Nearby is an elaborate water feature with streams tumbling over rusty-brown rock. Frozen in sculpture, a family of elephants marches toward a whimsically curved swimming pool overlooking the Niger River.

Hima’s residence in Niger’s capital is an ostentatious display of wealth in a country that ranks dead last on the United Nations Development Index, which measures a nation’s well-being based on indicators like life expectancy and access to education.

Hima also owns three apartments in the Czech capital, Prague worth over $2 million in total. He acquired them in 2015, first shelling out $1.5 million for a penthouse in the Dock Marina, a luxurious residential complex on the Vltava River that allows residents to park their boats near the entrance. He purchased two more apartments in the development in the following months.

Hima’s business interests in Prague go beyond property. His now-defunct Nigerian company, Brid A Defcon, frequently partnered with a Czech-registered firm with a similar name, Defcon s.r.o, in 2009, according to the audit.

In 2017 and 2018, the Czech firm fulfilled a $33.6 million contract from Niger’s government to deliver 80 trucks manufactured by the Austrian firm Steyr. Supposedly bidding against Defcon s.r.o was the Algerian branch of Motor Sich. Brid A Defcon submitted the bid on behalf of Motor Sich, which it controlled, in an apparent attempt to show the process was competitive.

Motor Sich managers said it had never made such a bid, leading auditors to conclude that the company name had been “usurped.”

Such deals fueled Hima’s luxury lifestyle and made him the most conspicuous of Niger’s illicit arms traders, said Diallo, the anti-corruption specialist, adding that it was “no surprise” that he invested his profits abroad.

“Charfo has buildings in Niamey, but he and the others are less visible than [Hima]," he said.

Diallo said the corrupt arms deals “not only exposed a hidden financial cost to Niger — the poorest country in the world — but also showed how Niger’s sovereignty was captured and exploited.”

Additional reporting by Marshall Van Valen in Abidjan, Pavla Holcova in Prague, Elena Loginova in Kyiv, and Juliet Atellah in Nairobi.