Reported by

The staff at the Eetcafé Oppe Platz pub in central Echt didn’t know that quiet Tuesday in September 2024 that they had served their last plate of bitterballen, a fried Dutch snack.

With dart boards, retro gambling machines, and a thumping dance floor, the pub was one of Echt’s most popular venues, drawing lunchgoers in the day and a young crowd from across the area to its dance floor at night.

But in the pub’s attic that autumn day, a disaster was quietly unfolding.

A view of the Eetcafé Oppe Platz in central Echt, the Netherlands.

Outside in the brick-paved market square, a Dutch police surveillance team was keeping a close watch. Finally, at around 4:30 p.m., a group of armed police made their move: Wearing gas masks and special hazmat suits, they stormed the establishment.

In the attic, officers discovered not just a full-blown synthetic drug laboratory — complete with all the equipment and ingredients to manufacture amphetamines — but an enormous chemical spill.

The unknown substance that had leaked onto the floor was so potent that the soles of their shoes burned off, said Jos Hessels, the bespectacled mayor of the Echt-Susteren municipality in the thin tail of the southern Netherlands.

Jos Hessels, the mayor of Echt-Susteren, at his office on January 20, 2026.

For decades now, the Netherlands has dominated the international market for synthetic drugs, with the production heartland concentrated in the country’s southern provinces.

“The Netherlands is a kind of Valhalla for that.” said Hessels. “The profits are extreme.”

Synthetic drugs like ecstasy pills and MDMA produced by criminal syndicates in the region are sold worldwide, with the European MDMA market alone worth almost 600 million euros, according to the European Union Drugs Agency.

The marginal cost of producing an ecstasy pill is just 0.03 euros, while each pill can be sold in Australia for the equivalent of 13 euros, he said.

In the fight against the crime syndicates that plague his city, Hessels has formed a bond with Police Chief Marcel Hellinga, a veteran who spent nearly 25 years as a street cop busting cannabis plantations and criminal gangs in the province. Hellinga refers to the mayor fondly as “our Jos.”

Together, they are locked in an asymmetrical battle against forces with more money and fewer scruples, who are adopting new tactics — ones that use the municipality's 32,000 residents as camouflage for highly toxic and combustible operations.

Rural buildings, abandoned barns, and isolated sheds have long been popular sites for clandestine synthetic drug labs in the region, the pair said. But now, drug gangs are increasingly setting up their labs in residential areas of Echt, even slipping notes into mailboxes that offer up to 1,000 euros a month to rent a spare room.

“It’s a great place to hide — no one expects it,” Hellinga told OCCRP.

“Where is the lowest chance of being caught? Well, above a café, perhaps. It is very daring.”

It’s also dangerous. Amphetamine production uses large amounts of strong acids and volatile solvents, chemicals that can be highly toxic or explosive, even in small quantities.

The day before the police raid, a neighbor complained to the mayor’s office that the Eetcafé had started to take on a pungent chemical stench, Hessels said.

Even as the chemical seeped into the floorboards and down the pub’s exterior walls, the cafe remained open for business, serving a menu heavy on schnitzel and light on salads.

“It was like a scene from a bad film,” said Hessels, shaking his head. “It was dripping through the ceiling.”

Echt’s main street.

A Cat-and-Mouse Game

While the rolling hillsides and forests around Echt are a scenic lure for tourists, its main boulevard — lined with discount stores, a pawnshop, and several empty or crumbling storefronts — hints at a city in post-industrial decline.

This part of Limburg province never fully recovered from the closure of the local coal mines half a century ago, an event that cemented a long-standing distrust of authority in a border region long overlooked by the Dutch state and with a rich history of cross-border crime.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, smuggling was a survival strategy in the area, which is sandwiched between Belgium and Germany. Butter, salt, tobacco, and coffee were taken across borders to avoid paying taxes, or because they were simply cheaper on the other side of the border.

Smuggling was such an important part of the local economy that companies now offer bike tours along old smuggling routes.

“Play the cat-and-mouse game in the border area of De Groote Heide and follow in the footsteps of the smuggler,” reads the local government tourism website.

Today, Echt-Susteren is caught in the crosshairs of a multi-billion-euro illegal narcotics industry. With two of Europe’s busiest ports, Antwerp and Rotterdam, around a two-hour drive away, Echt still lies at a trade crossroads, making it attractive for legitimate logistics companies — but also for organized crime.

Locations related to amphetamine production in the EU from 2019 to 2021 — including production sites, storage facilities, and waste dumps — were particularly dense in the southern Netherlands, around Echt.

Data source: euda.europa.eu

Echt is less than 5 kilometers from the borders of both Belgium and Germany, making it an attractive area for trade — but also for drug smuggling.

The walls of Hessel’s spacious office — a 10-minute walk from the Eetcafé — are adorned with a portrait of the Dutch king and queen, framed family portraits, and memorabilia, including a police officer's cap.

Out the window one recent Tuesday, market vendors stacked dozens of yellow cheese wheels onto a wooden market stall. An elderly woman with a small white poodle in a pram bought fried fish from a fishmonger.

“People see a quiet rural town,” Hessels said. “A few burglaries, hardly any robberies, bicycle thief, that’s it. But serious crime is constantly increasing.

"In the background there is an increasing blend of the criminal underworld and legitimate society.”

The municipality’s rate of drug offenses — including production, trade, and possession — is far above the Dutch national average. Weapons offenses are around 76 percent higher.

Younger residents are often pulled into the criminal economy for relatively small sums.

“For 500 euros, give a young person a weapon and they will shoot,” Hessels said.

Some are recruited to retrieve cocaine shipments from Antwerp’s port in exchange for as little as a bicycle with fat tires, a new iPhone, or a night out, the mayor said.

“Drugs, women, human trafficking, weapons. Particularly drugs. It’s only increasing,” he said. “Everything passes by here.”

Dutch police making an arrest at the port of Rotterdam, the Netherlands. In 2024, the police arrested 266 people for retrieving drug-filled containers or packages from the port before they reached customs control.

Biker Gangs, Drug Labs, and Barrels of Toxic Waste

Hessels pushed his metal-rimmed glasses up his nose and gestured animatedly with his hands as he explained the challenges and triumphs of his past 15 years as the mayor of Echt.

The 60-year-old has sent a handwritten card to every newborn in the municipality for more than a decade.

He doesn’t just participate in the popular spring carnival — a southern Netherlands tradition, complete with the crowning of carnival princes and princesses, brass bands, parties, and parades — he used to chair the regional association of carnival groups.

In spite of Hessel’s evident enthusiasm for the city, he’s not there to be liked, he said.

He’s faced nearly every category of organized crime scourge, from biker gangs to covert drug labs, money-laundering operations posing as high street shops, a drive-by shooting, and barrels of toxic drug waste dumped in fields around his beloved city.

In striking back at the criminals drawn to Echt, he’s shut down scores of houses, barns, sheds, and warehouses.

The Dutch Mayor's 'Sword'

In the Netherlands, mayors wield a controversial legal "sword" known as the Damocles Act, part of the Dutch Opium Law.

In 2024 alone, he temporarily shuttered around 27 buildings used to stash or produce drugs, a significant increase from 2023, using powers granted to mayors to help restore public order and safety.

“You accumulate people who don’t like you. And behind them are organizations who like you even less,” he said.

Ten years ago, Echt was in the eye of the storm of a war between two motorcycle gangs, the Hells Angels and the Bandidos, Hessels said.

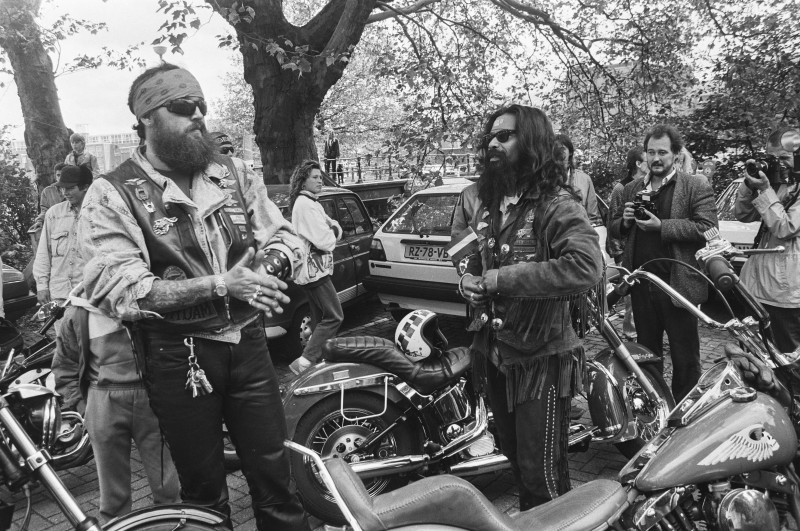

Hells Angels members in Amsterdam on June 24, 1987.

In the Netherlands, local chapters of these motorbike groups have a documented history of involvement in the narcotics trade.

In 2021, a court in Limburg convicted 12 members of the Bandidos for violence, threats, theft, and money laundering.

Once, a convicted murderer threatened Hessels, forcing the government to equip his home with extensive security measures.

Another time a TV crew was filming him in front of the house of a suspected drug trafficker when a masked man on a moped rode up to him.

“It stops, and you see that under his helmet he’s wearing a mask as well. And he just stands there, staring, for about a minute. Just provocatively, just watching,” Hessels said. “And then rides off again in the same way. Just to say, ‘We’re watching you.’”

'A nose for vulnerable people'

For around half a dozen years, the Eetcafé was run by Richard S., his wife, and son — well-known figures in the tiny city.

The family rented the pub from Bavaria, one of the oldest breweries in the Netherlands, whose huge black and white sign hangs on the wall above the door.

“We were a cafe for everyone, young and old," Richard S. told a Roermond court in January as he and his 23-year-old son Romano S. were charged with manufacturing drugs with the intent of selling. (In the Netherlands, criminal suspects often have their full names withheld by courts until their cases have been fully adjudicated.)

Judges at a provincial court in the city of Roermond, the Netherlands, hearing the case of Richard S. and his family on January 20, 2026.

On February 3, the court sentenced Richard S. to two and a half years in prison. His son, Romano S., received a 20 month jail sentence. Richard S.’s wife Melinda, who was accused of aiding and abetting the alleged crime, was acquitted.

Two weeks earlier the men had pleaded guilty to producing around 4.5 liters of amphetamine oil — a base substance that can be converted into “speed” or added to ecstasy pills — for a criminal organization, and faced a combined fine of approximately 55,000 euros. It was not clear why Melinda S. did not attend the court hearing.

Confronted with DNA evidence, surveillance tapes, and messages on their mobile phones, Richard S. and his son admitted to having set up a lab in the attic, but claimed they hadn’t put their customers in danger.

Sitting on the wooden defendant’s bench, Richard S. wore jeans and a blue short-sleeved shirt. His hair was stiff with gel; a large bicep tattoo twitched every time he moved his arm.

"The café started in good times, but then the coronavirus pandemic hit, and we had a lot of debt. We tried everything to get out of the Bavaria contract."

Then "someone approached us to get rid of our debts," Richard S. told the court.

Richard S. said he was too afraid to name the person who had offered him this deal, but that he had been assured he could earn a lot of money by setting up the drug lab.

"Unfortunately, my son got involved, which is just stupid," Richard S. said.

It’s a pattern Hellinga and Hessels have seen time and again — drug gangs target people who are struggling financially and offer them cash to use an empty building or room.

“What you often see is that they have a nose for vulnerable people,” Hellinga told OCCRP.

The drug lab set up by the father and son in the attic of the pub operated for about six weeks, from August 5 to September 24, 2024, according to prosecutors.

That summer the Eetcafé “was the place to be,” said Milan Dekkers, an 18-year-old waiter in Echt. “Every weekend there was a party, and everyone was there.”

"We never did anything when people were in the building,” said Richard S. "We were told it wouldn't do any harm.” A leak only occurred during the cleanup, he said.

Hessels was less nonchalant about the risks posed by the 40 liters of formic acid, 130 liters of hydrochloric acid and around 90 liters of formaldehyde, all highly flammable or toxic liquids, found by police in the attic.

“Every weekend hundreds of young people were put in mortal danger,” Hessels said.

The Limburg Court ultimately agreed.

“The court can’t begin to imagine how many casualties and damages would have occurred if this lab had exploded. The defendant apparently ignored this danger," read the judgement against the two men.

'Mopping with the taps open'

The police raid on the Eetcafé wasn’t triggered by the neighbor’s tip-off about the chemical stench, but by a clumsy mistake in a garage a few minutes’ drive away, prosecutors said.

Just after noon on September 24, a joint municipal-police team were conducting what they said was a routine sweep of empty garages in the city, looking for synthetic drug labs or stashes of precursor materials — a necessity in the region.

“All of a sudden the garage door goes up and a stench hits them,” Hessels said. The garage was chock full of kettles, pipes, hoses and chemical residue: the paraphernalia of a synthetic drug lab, Hessels said.

It didn't take the officials long to find the next clue. A big leaking barrel at the front of the garage bore a sticker with the address of the Eetcafé Oppe Platz: Plats 5.

“Literally. You couldn’t make it up. Hilarious,” Hessels said, chuckling loudly.

Hellinga’s police surveillance team immediately moved into the market square. As the lunch crowd came and went, police watched Richard S. and his son with blue gloves on, loading lab equipment into cars or chucking it in the dumpster, the prosecution alleged.

At around 4:30 p.m., armed police in protective gear moved in.

While the “Plats 5” sticker was a moment of levity for the mayor, it shows how the billion-euro narcotics industry has managed to weave itself into the mundane corners of this small city.

Another burden is cleaning up the mess when gangs dump the toxic waste from drug production in the countryside.

Nationwide, 217 drug-waste dump sites were found in 2024, the highest since 2018. In Limburg alone, police recorded 42 dumping incidents last year, up significantly from the previous year.

Belgian and German criminals also cross the border to dump the drug waste near Echt, Hessles said. “The three governments don't always communicate well. So your chances of being caught are significantly smaller by cleverly using the border.”

Four years ago drug waste disposal cost the municipality 20,000 euros. By last year, the cost had risen to 120,000 euros, Hessels said. “This year it is increasing again.”

Back at the city’s square, the pub’s extensive clean-up will soon be complete. Hessels is keen to take down the posters reading “Closed by order of the mayor” and return the square to a buzzing nightspot.

“We hope a good, respectable operator will move in there and start a nice business,” he said.

We as government have the huge handicap that we have to abide by the rules. ... It's like mopping with the taps open.

Jos Hessels, Mayor of Echt

But so far, no one has rented the place. The beer taps and red leather bar stools are gathering dust.

Busting one drug lab was a minor victory, but the growing influence of a better-funded opponent can feel overwhelming, even for somebody with Hessels’ level of optimism.

“We as government have the huge handicap that we have to abide by the rules,” he said. “We've lost. It's like mopping with the taps open.”