On April 3, the market also offered a dozen large sharks whose fresh blood reddened the wooden pallets they were displayed on.

The bluntnose sixgill shark, Hexanchus griseus, or simply “cow shark” is “Near Threatened,” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. While cow shark is less endangered than other shark species, the species is threatened with extinction in the near future and the European Union regulated fishing it.

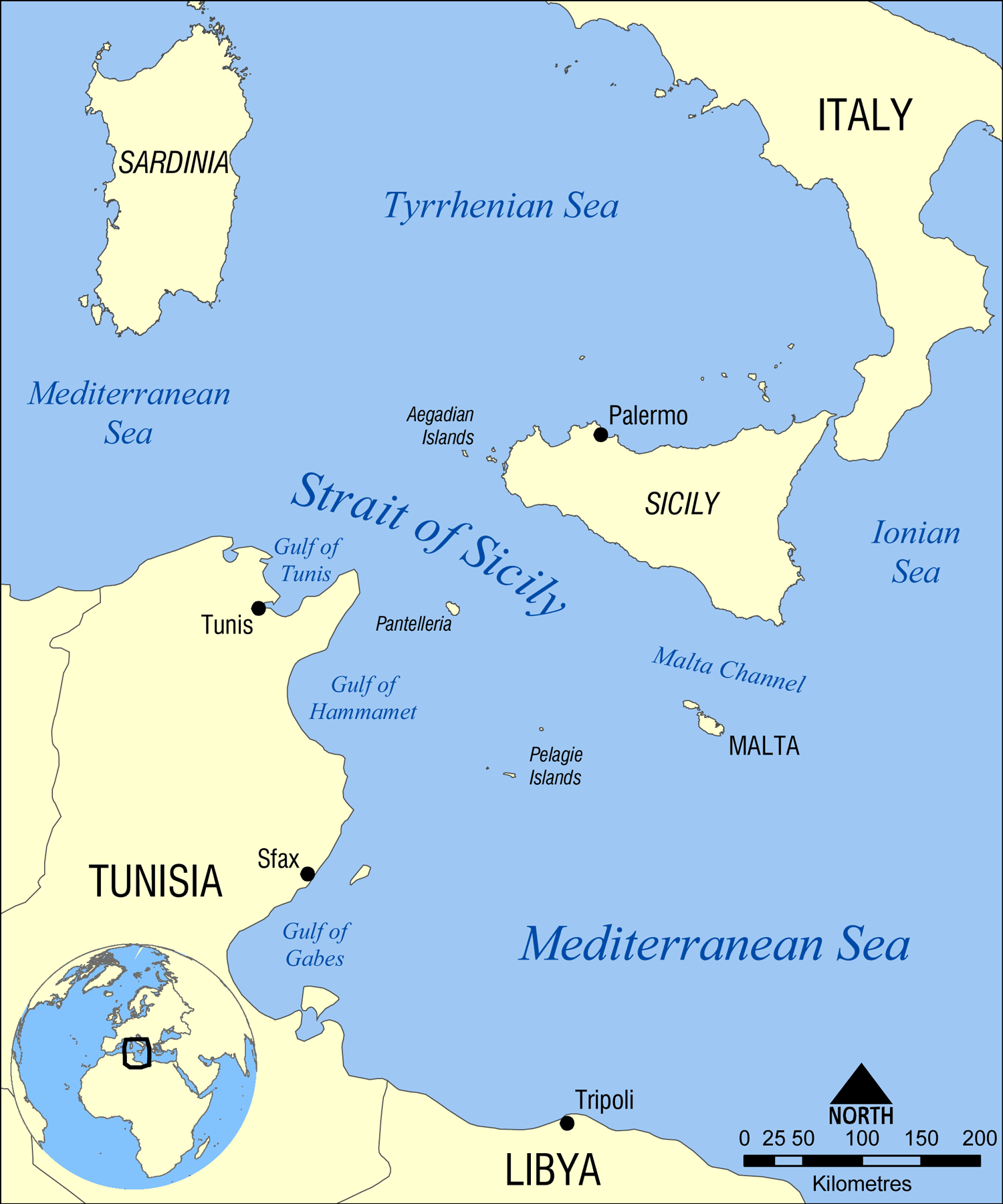

But those regulations do not apply in Tunisia, which makes it, along with other migratory species, hard to protect. In the Gulf of Gabes, south of Kelibia, the sharks are commonly hunted, offered laying belly-down in markets, and smuggled to Italy.

This trade could damage not only the Mediterranean Sea’s ecosystem but also its fishing communities.

Kelibia lies on a northeastern stretch of Tunisia that juts out into the water right across from the Italian Island of Pantelleria. The Tunisian port is less than 100 nautical miles away from Mazara del Vallo — a city on the west coast of Sicily with the largest fishing fleet in Italy.

Most of the Mediterranean’s illegal shark trade takes place along this strip of sea, known as the Strait of Sicily, where Tunisian fishing boats meet Sicilian partners to tranship their catch.

In the Tunisian region of Sahel — the coastal strip that goes from the Gulf of Hammamet down to the Gulf of Gabes — shark meat is a crucial ingredient of traditional cuisine. But when the shark meat enters the Sicilian black market, it is sold as swordfish, according to The Guardian.

Tourism in the Sahel has declined due to terrorism threats and, more recently, the coronavirus, and now fishing is the primary source of income, with thousands of fishing vessels sailing the gulf every day.

This dramatic increase in fishing could mean that sharks will soon disappear from Tunisian waters forever.

Most of the time, fisherman catch sharks when they get entangled in nets meant for other fish, but some actively hunt sharks using baited longlines. This happens particularly around Kelibia, according to Sami Mhenni, a marine engineer and the president and founder of HOUTIYAT, a Tunisian environmental association specialized in protecting sharks.

Fishermen display the cow sharks they caught in Kelibia on April 3, 2020. (Credit: Facebook)Jamel Jrijer, a marine program manager with the World Wildlife Fund for North Africa, says that about 20 percent of shark caught in Tunisia is not done so accidentally but illegally.

Fishermen display the cow sharks they caught in Kelibia on April 3, 2020. (Credit: Facebook)Jamel Jrijer, a marine program manager with the World Wildlife Fund for North Africa, says that about 20 percent of shark caught in Tunisia is not done so accidentally but illegally.

“There are two fishing fleets that go and hunt for them: The one of Kelibia and the one of Zarzis,” he said, referring to a town further south, toward the border with Libya.

Fishermen themselves present evidence of the illegal catches.

In Facebook posts from 2019, Kelibian fishers show countless catches of protected species, including great white sharks, shortfin makos and even a giant devilfish.

On April 3, 2020, the Facebook profile “Sailor of Kelibia” posted a video showing at least 20 cow sharks being sold in front of a warehouse that looks like the one run by Kelibia fish market managing company Il Marchi, which is registered as “ILMARCHI” in Tunisia.

Il Marchi’s website promises to deliver fish anywhere in Tunisia within 24 hours and the company advertizes its catches of cow sharks.

“Fishing this type of shark is legal and the sales were checked by the Ministry of Health on the spot,” the company said on Facebook, referring to the sharks displayed on the market on April 3.

“This is happening every day in several parts of Tunisia, but the sales are not marketed or publicly recorded, as they are not posted on social networks,” according to the company.

Nobody in Kelibia seems to be bothered by shark fishing. Displayed on the port’s dock, a particularly large shark is a trophy that captures people’s attention. Fishermen tend to brag on social media about the size of their catch — from rays to sharks.

A high demand for shark fin on the black market makes it very profitable to keep fishing these big animals. One contributor to this demand are Asian restaurants in Europe that serve shark fin soup as a delicacy.

The main problem with combating illegal shark fishing is the lack of information and training among fishermen and the officials who are supposed to enforce the law and check catches, said Fabrizio Serena, a researcher at Italy’s Institute for Biological Research and Biotechnology, IRBM-CNR, and the regional vice-chair of the Mediterranean shark specialist group of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, IUCN.

“Fishermen are not able to tell protected species apart from those that are not,” Serena said. “The laws keep changing and it’s crucial to organize information campaigns for fishermen.”

The General Fishery Council for the Mediterranean, GFCM, tries to address this issue in North Africa, and had planned for Serena to give a training in Tunisia this spring but the event was cancelled due to the coronavirus pandemic.

The port of Kelibia as seen from the town’s byzantine fortress. (Credit: Sami Mlouhi (CC BY-SA 2.0))

The port of Kelibia as seen from the town’s byzantine fortress. (Credit: Sami Mlouhi (CC BY-SA 2.0))

While some might not know what they catch, other fishermen simply do not care.

In 1975, Tunisia adopted the Barcelona Convention, which includes regulation on which species of fish have to be released back into the water when caught and when fishermen need to report catches to the authorities.

But fishermen hunting for sharks are not afraid of the authorities and operate like a mafia, including an unwritten code of silence; a sort of “omerta,” Jrijer said.

“They are well organized and if attacked by authorities or the media, they retaliate,” he said. “They can do that because they are backed by unions that are so strong that they often have influence over the decision makers.”

Activists and coast guards who tried to stop shark fishing or even just check fishing boats and seize the dead animals have been beaten up and their cars were set on fire, local activists told OCCRP.

The intermediaries that get the fish from fisherman to consumer often try to hide what kind of meat they are selling. They slice the sharks up and mix the pieces with tuna or swordfish, making it almost impossible to tell what kind of fish is being sold.

In many cases, restaurants, supermarkets, food distribution chains and hotels knowingly buy shark meat because they get more for their money.

As hotels offer “all-inclusive” packages, a large shark means less costs for the kitchen serving a large fish buffet, Jrijer said. Some hotels even present the sharks openly, hoping to attract more tourists.

Regarding accidental catches, punishing the fishermen can be counterproductive.

“Sanctions … cause a lot of worry among fishermen,” Serena said. “What we need is a tracking system like the one in place for turtles or other marine mammals.”

With such a system, fishermen can inform the coast guard when they capture a tracked shark. The coast guard can then contact the closest marine research institute, which in turn can register and free the captured animal.

A map of the Strait of Sicily, between Tunisia and the Italian island. (Credit: Norman Einstein (CC BY-SA 2.0))“If we don’t do it this way, the consequence is that the fisherman who by-catches the shark will end up selling it illegally to avoid problems,” he said.

A map of the Strait of Sicily, between Tunisia and the Italian island. (Credit: Norman Einstein (CC BY-SA 2.0))“If we don’t do it this way, the consequence is that the fisherman who by-catches the shark will end up selling it illegally to avoid problems,” he said.

The shark population of the Gulf of Gabes is a precious resource; its protection is crucial for the Mediterranean Sea’s ecosystem. Tunisian fishermen are shooting themselves in the foot when catching sharks, Serena said.

The predator is at the top of the food chain, and his extinction would have a devastating impact on the fish stock.

“Sharks have a role of regulating the whole sea’s food chain,” Serena says.

When North Carolina killed most of the sharks that prey on ray fish, the ray population grew exponentially, in turn destroying the stock of scallops on which fishermen depended. As a result, the local fishing industry withered as well.

The same thing could happen in Tunisia.

“If they disappear,” Serena warns, “the whole economy of a region could collapse … the ports and the existence of people dependent of them.”