Lebanon's navy failed to raise alarms about a potentially deadly payload of ammonium nitrate aboard the MV Rhosus cargo ship during a 2013 inspection — seven years before the chemical caused a devastating explosion in Beirut that killed over 200 people.

Documents obtained by OCCRP show that the Rhosus was flagged for inspection by a U.N. maritime peacekeeping force when it arrived at the Port of Beirut in November 2013. The Lebanese navy boarded and examined the ship but failed to flag its combustible cargo, according to the documents.

“The vessel was clear and nothing illegal was reported,” the navy wrote in a brief report at the time.

The fact that this inspection took place was omitted from a comprehensive Lebanese Armed Forces report submitted to the Defense Ministry on August 9, 2020, five days after the blast, which destroyed a large swath of Beirut and displaced hundreds of thousands of people.

Although the four-page report provided a detailed timeline of events related to the ship and its cargo, starting from even before it entered the port’s waters in 2013, it never mentioned the naval inspection.

The office of Lebanese President Joseph Aoun — who was commander in chief of the Armed Forces from 2017 until his election as president last year — did not respond to requests for comment. Questions sent to Lebanon’s military also went unanswered.

The new findings “raise serious questions regarding the responsibility of individuals, including those within the army, who inspected the M/V Rhosus and cleared it to be docked in Beirut’s port, despite the fact that it was carrying thousands of tons of unstable material," said Lama Fakih, Global Program Director at Human Rights Watch.

“Officials also need to interrogate and explain why the army has never reported this November 2013 ship inspection. It is time for accountability for those responsible for the Beirut blast."

A ‘Vessel of Interest’

The documents obtained by OCCRP show that on November 20, 2013, as the Rhosus was sailing into Beirut’s port, the UNIFIL Maritime Task Force — a U.N. peacekeeping body that helps Lebanon monitor its waters and prevent the unauthorized entry of arms — flagged it as a “vessel of interest.” They asked Lebanese authorities to inspect it, according to what is known as a “hailing report” issued by the task force that day.

The UNIFIL Maritime Task Force flags vessels as “of interest” if they exhibit suspicious behavior, carry suspicious cargo, or enter or leave the port unexpectedly.

UNIFIL did not respond to questions on why the Rhosus was flagged, and records from the time do not make it clear, although a document obtained by OCCRP that appears to have been attached to the hailing report mentions that it is carrying “amonion 2755 nitraton.”

The ship’s bill of lading also stated that it was transporting 2,750 tons of high-density ammonium nitrate, while a cargo manifest said the material was being sent to an explosives company in Mozambique.

The material was stored in bags labeled “Nitroprill HD,” with symbols indicating that there was hazardous combustible material inside, according to photographs of the cargo seen by OCCRP.

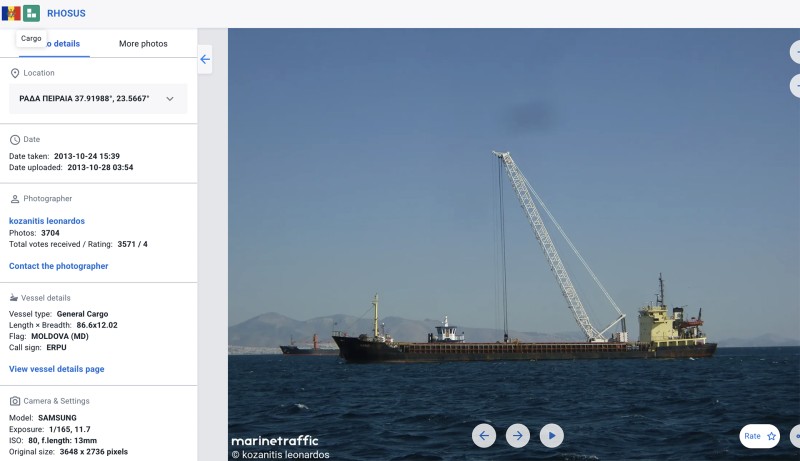

The Rhosus seen off the coast of Greece on October 24, 2013.

Later that night, the Lebanese naval forces sent a short report to UNIFIL, saying they had boarded and inspected the ship “in front of Beirut port.” It does not mention the ship’s contents.

Ammonium nitrate is used to make both fertilizers and explosives, and is regulated in Lebanon under the Weapons and Ammunition Law, which categorizes it as a “material used in the manufacture of explosives” if it has a nitrogen content above 33.5 percent.

The Lebanese Armed Forces, which include the navy, did not respond to questions on the inspection. UNIFIL said that its role in the operation had been limited to flagging the ship.

“Lebanon is a sovereign country,” it said. “Only the Lebanese authorities have the authority to decide whether and how to carry out a ship inspection.”

'Criminally Negligent'

Hazardous cargo aside, the Rhosus was not in good condition in the months preceding its arrival in Beirut. In June 2013, a Lebanese inspection in the port of Saida found 17 defects in the ship, including hull corrosion and defective navigation equipment, according to maritime database Equasis.

Although it was allowed to dock in Beirut after its navy inspection, it was ultimately abandoned and impounded. The ammonium nitrate it carried was moved into a warehouse at the port in 2014.

It was left in unsafe storage conditions there for the next six years. Documents show that various Lebanese authorities — including the army, port authorities, customs, and government ministries — spent years debating which of them was ultimately responsible for disposing of the chemical. The derelict Rhosus, meanwhile, sank in port in 2018.

Families of Beirut port blast victims protest outside Lebanon's parliament on July 10, 2021, calling for a fair investigation into the 2020 explosion.

Five days after the explosion, following a request from the prime minister for a detailed account of the events, the army’s operations command addressed a report labeled “top secret” to the Ministry of Defense.

That report, which was signed by General Joseph Aoun, the current president, provides a detailed timeline of what happened to the Rhosus and its cargo. But it never mentions the navy’s 2013 inspection — nor that it had declared the vessel “clear.” It is unclear why the inspection is omitted.

The report does note that the army received warnings from port authorities in 2014 that the ammonium nitrate was dangerous and should be transferred to the army or re-exported. But the army refused to take charge of the chemical, saying it had no use for it, and no capacity to store or destroy it.

In an extensive 2021 review of the incident, Human Rights Watch found evidence that multiple authorities had been criminally negligent in their handling of the explosive cargo, by failing to recognize how dangerous it was, securing it poorly, and communicating inadequately with other authorities about the risk.

Lebanon’s government has also been criticized for its handling of the investigation into the blast, which has not yet been concluded more than five years after the disaster, due in part to repeated challenges to the judges leading the probe. The judges have also struggled to get high-profile witnesses to testify. In 2023, the U.N.’s special rapporteur on judicial independence said she was concerned that these delays amounted to political interference.

In early February, Lebanon’s official press agency reported that an indictment in the investigation was expected to be handed down soon.

“For too long victims and their families have waited for answers about who was responsible for the explosion that devastated Beirut and killed and injured so many,” Fakih of Human Rights Watch told OCCRP.