Russian President Vladimir Putin insists that while the Panama Papers stories published by Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and its partner Novaya Gazeta are correct, they show no corruption or illegal activity on his part. Putin has called the stories a Western plot to destabilize his regime.

But additional analysis of the records by OCCRP and Novaya Gazeta show that offshore companies connected to Sergey Roldugin, one of Putin’s oldest friends, profited obscenely in building the jewel of the financial empire of Putin’s inner circle: Bank Rossiya.

And not only that, Bank Rossiya itself has profited massively at the expense of Russian taxpayers.

Bank Rossiya featured prominently in earlier OCCRP stories that showed Roldugin used offshores to conduct a series of highly suspicious transactions, many of which made no financial sense but left Roldugin much wealthier.

Documents showed that Roldugin and his associates owned a number of offshore companies registered in the notorious tax havens of the British Virgin Islands (BVI) and Panama. Billions of dollars flowed through the companies, which received “donations” from Russia’s richest businessmen and controlled the activities of strategic Russian enterprises.

Bank Rossiya employees figured prominently in many of the transactions.

The bank is described by the US Treasury Department as “the personal bank for senior officials of the Russian Federation” whose “shareholders include members of Putin’s inner circle associated with the Ozero Dacha Cooperative, a housing community in which they live[d]”.

New records found by OCCRP show that in 2010, a company linked to Roldugin bought shares of Bank Rossiya for US$ 6.50 per share and sold them just days later to an unknown investor for 32 times more than he paid for them. Within a month, Gazprom, Russia’s largest state-owned company, paid more than 169 times what he had paid for the same shares: US$1,120 per share. Even worse, Gazprom would later sell most of them again for half that price earning large losses.

The records detailing these transaction were obtained by OCCRP from public records and the Panama Papers, a set of documents that were leaked from an offshore services provider called Mossack Fonseca to the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) with more than 100 media partners across the globe including Novaya Gazeta and OCCRP.

Putin, however, was adamant that the Panama files demonstrate no corruption or illegal activity on his part. “They are just trying to cause confusion, saying that some of my friends are involved in business, and suggesting that some of the money from these offshore accounts finds its way to officials, including the president,” he said.

"Putin's Bank"

As retaliation for the annexation of Crimea and Kremlin support for pro-Russian separatists in Eastern Ukraine, authorities in both the US and European Union (EU) imposed sanctions on individuals and companies from Putin’s inner circle. One of the most important targets was Bank Rossiya.

Many of the figures involved in the bank owned houses in the Ozero Dacha Cooperative near Putin. The cooperative, founded in the mid-1990s, is a gated community of summer homes on the shores of Lake Komsomolskoe near St. Petersburg. One of his neighbors was Yuri Kovalchuk, the largest shareholder of Bank Rossiya (with about 38 percent). Kovalchuk, 64, is considered by EU authorities as Putin’s long-time acquaintance who is benefiting from his links with top Russian decision makers.

At various times, Bank Rossiya shareholders have included Nikolay Shamalov (his son, Kirill, is married to Putin’s younger daughter Katerina Tikhonova); Mikhail Shelomov, a distant relative of the president; and Roldugin, a celebrated cellist and godfather to Putin’s oldest daughter.

The bank was established in 1990 in the twilight of the Soviet era with the participation of the St. Petersburg branch of the Communist Party. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, new investors stepped in. They included Kovalchuk, former Minister of Education Andrei Fursenko and former Russian Railways head Vladimir Yakunin – all long-time friends and associates of Vladimir Putin.

In the mid-1990s, they were joined by powerful St. Petersburg criminal: Sergey Kuzmin and Gennady Petrov and companies affiliated with them controlled a significant stake in Bank Rossiya up until the end of 1990s when Putin became the head of the FSB, the Russian intelligence agency, and later the leader of the country. Last summer Petrov was indicted by Spanish prosecutors as a leader of the Tambovskaya organized crime group and accused of money laundering, fraud and other crimes.

Today Bank Rossiya is among the top 20 Russian lenders according to the Interfax rating agency, with assets of about US$ 9 billion and equity of US$ 700 million. It controls a sprawling financial empire with important strategic assets that underpin the Russian economy, including one of the country’s largest insurers and the management company for Gazprom’s pension fund.

One of Bank Rossiya’s holdings owns 25 percent stake in Channel 1, a state-controlled TV network with the largest audience in Russia.

The Panama Papers detail how a few suspicious deals involving Bank Rossiya’s shares helped a company linked to Roldugin make a fortune in just two days.

Buy, Resell — Become a Millionaire

One of the companies affiliated with Roldugin is Sandalwood Continental from BVI. Starting in 2007, Sandalwood belonged to Oleg Gordin, a businessman from St. Petersburg who has acted as Roldugin’s authorized representative in other companies. Internal documents from Mossack Fonseca show that Sandalwood held billions of US dollars.

The company got loans on preferential terms from the Cyprus-based RCB Bank, a large stake of which is controlled by the Russian state-owned VTB Bank. Sandalwood invested some of their funds in luxury projects linked to Putin. For instance, Sandalwood then gave loans to a Russian company called Ozon, which owns the ski resort Igora, not far from St. Petersburg.

Reuters reported last year that Igora was the site of the 2013 wedding between Putin’s daughter Tikhonova and Kirill Shamalov, son of the long-time Putin friend and Bank Rossiya shareholder Nikolay Shamalov.

On June 23, 2010, Sandalwood bought 66,198 shares (about 3 percent of the share capital) of Bank Rossiya from Evgeny Malov. Malov is another well-connected businessman from St. Petersburg.

Malov was a business partner of Gennady Timchenko, another Putin friend, until they split their business interests in the mid-2000s. Timchenko was a cofounder of an oil-trading firm called Gunvor, a company that trades much of Russia’s oil.

Credit: REUTERS/Alexander Demianchuk

Gunvor

According to the US Treasury Department, Gunvor is “one of the world’s largest independent commodity trading companies involved in the oil and energy markets. Timchenko’s activities in the energy sector have been directly linked to Putin. Putin has investments in Gunvor and may have access to Gunvor funds.”

Timchenko is no longer a shareholder of Gunvor: on the day before the US levied sanctions against him, Timchenko sold his stake in the company to his long-time partner from Sweden, Torbjorn Tornqvist, “to ensure with certainty the continued and uninterrupted operations” of Gunvor.

The deal between Malov and Sandalwood was very lucrative for Sandalwood, which bought shares from Malov for 200 rubles per share (US$ 6.50), spending a total of 13 million rubles (about US$ 425,000) for the stake in Bank Rossiya.

Sandalwood held those shares for just two days. On June 25, 2010, Sandalwood sold the whole stake to another offshore entity from Cyprus, Horwich Trading, but at US$ 211.50 per share. So in the course of 48 hours, Sandalwood booked a profit of US$ 13.6 million, an astounding 32 times its initial investment.

OCCRP could not identify the owners of Horwich Trading.

From Small to Big

Sandalwood was not alone in winning big. Bank Rossiya would do an even bigger deal – one that transformed it into a major Russian bank.

In 2010, about one month after Sandalwood sold the shares to Horwich, Bank Rossiya took over Gazenergoprombank (GEP), owned by Gazprom, a state company, through its subsidiaries. Shareholders of Bank Rossiya ended up paying nothing for a bank which filled their coffers with billions of dollars and more than doubled their assets from US$ 3 billion to more than US$ 8 billion.

GEP was established in 1996 by Gazprom’s subsidiaries. Until 2010 the lender played a crucial role in the Russian gas industry by providing loans and accounts to gas distribution companies that were part of Mezhregiongaz Holding, the company responsible for gasoline sales across Russia.

In March of 2010, the board of directors of GEP approved a merger with Bank Rossiya. The deal allowed Bank Rossiya to take over GEP in exchange for newly issued shares of Bank Rossiya. No cash was included in the deal. But the deal turned out to be a very poor deal for taxpayers because the shares of Bank Rossiya, which are not openly traded, tended to change value in such a way that benefitted the private bank and its shareholders at the expense of the state.

Smallest Piece of the Pie

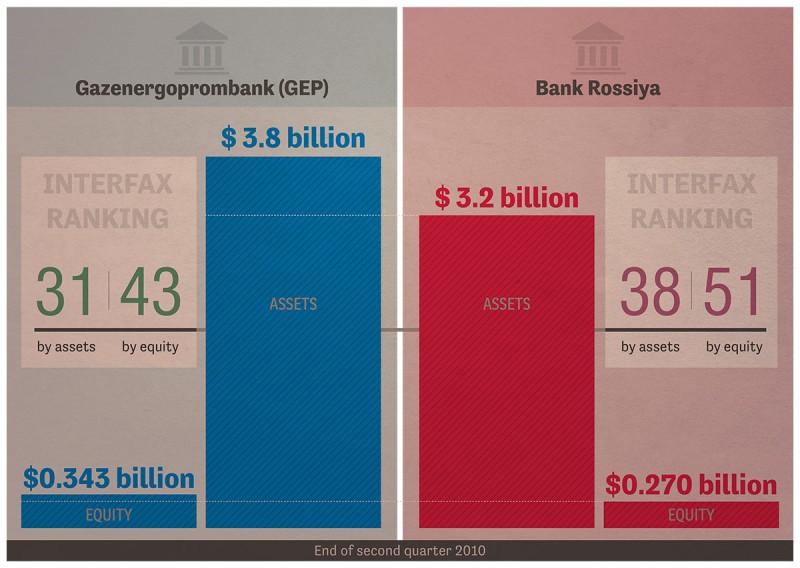

On the eve of the merger, in June 2010, GEP was a larger bank both in terms of assets and equity than Bank Rossiya according to the Interfax rating of Russian banks.

GEP was the 43rd largest bank by equity compared to Rossiya’s rankings of 51st.

Although GEP’s contribution to the combined bank was more than half the equity and assets according to their financial statements, GEP shareholders only got a bit more than 16 percent in the newly joined bank, according to Bank Rossiya’s 2010 International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) report.

Reporters for Novaya Gazeta/OCCRP showed these documents to three independent banking and financial analysts and all of them said the merger hurt the state-owned companies which controlled GEP. None of the experts agreed to talk on the record, since, as one said, “You understand who is behind Bank Rossiya.” According to their calculations, GEP’s shareholders should have received no less than 50 percent of the merged bank.

Records from the merger show that GEP was valued at US$ 475 million (including US$ 263 million in cash). To cover that amount, Bank Rossiya issued about 420,000 new shares to Gazprom which fully owned GEP, priced at US$ 1,120 per share. The price was 169 times more than what Sandalwood had paid one month previously. Gazprom would later sell these same shares for much less.

Gazprom officials said they considered the swap ratio fair and explained that auditors estimated Bank Rossiya share split by calculating assets of the larger Rossiya group and not just the bank.

Meanwhile, Bank Rossiya benefited from the merger. By the end of 2010, Bank Rossiya’s assets had more than doubled to US$ 8 billion and its equity had increased to US$ 660 million, while the deposits by corporate clients doubled as well. Bank Rossiya had become an important financial player in the Russian gas industry.

Novaya Gazeta sought comment on this series of transactions from Kovalchuk, Bank Rossiya’s largest shareholder, and Alexei Miller, the head of Gazprom. Neither responded.

Previously, a Bank Rossiya spokesman had told the newspaper Kommersant that the deal was approved by shareholders based on “independent estimations of both lenders” by the global accounting firms PriceWaterhouseCoopers and Deloitte CIS, which weighed “all assets of each member of the merger.”

Both auditing companies declined comment as well.

Calculating Losses for the State

It is possible to find out some of what Gazprom lost by looking at part of the deal. Before the merger, Gazprom subsidiaries owned all the shares of GEP. Gazprom Gazoraspredelenie, the main distributor of gas in Russia, owned 73 percent of GEP and got 12 percent of Bank Rossiya’s shares. But in late 2013, the board of directors decided to sell its shares.

Bank Rossiya shares were priced at the time of the merger at US$ 1,100making the share of Gazprom Gazoraspredelenie worth at least about US$330 million in 2010.

But in its 2013 report, Gazprom’s subsidiary reported selling their Bank Rossiya’s shares for much less than half that price or US$ 153 million (in exchange rates for December 2013). At 2010 exchange rates, the price would be about US$ 170 million, or half what they had paid in 2010.

However, during this time Bank Rossiya actually grew significantly. From 2010 until 2013, Bank Rossiya’s assets quadrupled, from US$ 3.2 billion to US$ 12.5 billion; its equity more than tripled from US$ 270 million to almost US$ 950 million; and its net profit grew almost 10 times, from US$ 17 million to US$ 155 million. With such robust grown, how the bank’s share value actually dropped is unclear.

Sandalwood, meanwhile, made a fortune on Bank Rossiya’s shares by simply buying and reselling them in two days. Shareholders of Bank Rossiya, connected to Putin since the 1990s, were also lucky by acquiring the valuable assets of a former Gazprom bank without paying any cash.

Not so lucky were the state-owned companies and Russian taxpayers, who had to pay grossly inflated prices for assets which cost almost nothing for the president’s friends.

Roldugin, Malov and Gordin did not respond to calls for comment.