Before his murder in Istanbul last November, Aierken Saimaiti disclosed a trove of secrets to reporters about his prolific money laundering from Kyrgyzstan on behalf of the Abdukadyrs, a secretive Uighur family.

Those revelations formed the basis of a multipart investigation by RFE/RL, OCCRP, and its Kyrgyz member center, Kloop, that triggered anti-corruption protests in Kyrgyzstan and rattled the Central Asian nation’s political landscape.

But Saimaiti’s murder left several mysteries lingering as well, including the true fate of £5.6 million he said he had sent to the United Kingdom.

One of Saimaiti’s most explosive claims was that this money went toward the purchase of a luxury London apartment for a senior Kyrgyz customs official. The funds, he claimed, were compensation for the official’s facilitation of an illicit cargo empire run by the Abdukadyrs, which made the family millions.

That official, Saimaiti said, was Raimbek Matraimov, who then served as deputy chief of the Kyrgyz Customs Service and who is notorious for his family’s lavish lifestyle, seemingly at odds with the salary of a career public servant.

The powerful but secretive former official has become a lightning rod for anti-corruption sentiment in the country, particularly since the earlier investigations implicated him in the operation of the Abdukadyrs’ illicit business.

The previous investigation also showed that Saimaiti funneled a portion of the proceeds from the Abdukadyrs’ business to a charitable foundation run by the Matraimov family and to Dubai, where they co-own a real estate project — bribes, he alleged, that compensated Matraimov for his cooperation. The Matraimov family has rejected these claims.

The planned purchase of the luxury apartment in Wren House, a swanky development close to the Thames River in historic central London would fit with what is known about the Matraimov family’s lifestyle. The former civil servant’s son attended an expensive private school in the city and has been seen wearing a watch worth tens of thousands of dollars; his wife is known to have visited London several times.

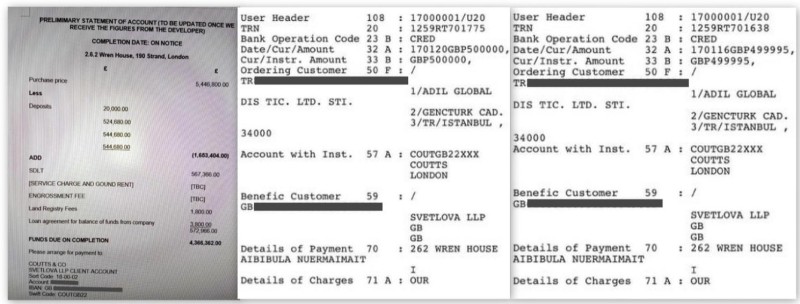

To support his claim about the alleged bribe to the Matraimov family, Saimaiti provided several documents, including a “statement of account” for the apartment and wire transfer records. The details in the documents match known information about the banks that were used to send the money, and the apartment’s purchase price listed in the account statement is close to what it ultimately sold for.

However, the story is murkier than it first appears.

Only two of the documents reference Matraimov, and those in handwritten form. The total the documents represent in wire transfers adds up to less than half of the value of the apartment. Moreover, after months of investigation, it emerged that the apartment was in the end purchased by a person with no apparent connection to the Matraimovs or Abdukadyrs.

It is unknown whether Saimaiti had evidence of additional wire transfers in his possession that he did not, or could not, give to reporters. It is also unclear why the purchase of the apartment did not go ahead, though the person who eventually bought it said that an earlier buyer had backed out. Saimaiti was murdered in Istanbul last November, and the full story of what happened may have died with him. This still leaves open the question of what happened to the £5.6 million Saimaiti claimed he sent — one of the last and most specific allegations of bribery he ever made.

Emails sent to the Abdukadyr family went unanswered. An advisor of Iskender Matraimov, Raimbek's brother and a member of parliament, asked for additional time to make a full response, but did not follow up before publication.

“London, Through Adil to Rayim”

“I transferred some money to England — £5.6 million,” Saimaiti told reporters. “We sent it for ... Raim[bek] Matraimov’s home. I don’t know whether the property is registered under his name or the name of someone else.”

Saimaiti said he had been instructed to arrange wire transfers toward Matraimov’s apartment in the name of Aibibula Nuermaimaiti, one of the sons of Khabibula Abdukadyr, the 56-year-old head of the Abdukadyr family, and that Nuermaimaiti had told him to record the transfers as Matraimov’s money.

To support his claim, Saimaiti gave reporters three documents directly related to the apartment: A preliminary statement of account for its purchase and two wire-transfer receipts.

The undated statement of account shows that the apartment had a listed purchase price of £5,446,800, plus some additional fees, confirming part of Saimaiti’s claim. It indicates that £1,634,404 had already been deposited toward the apartment, though it does not say where this money came from.

The two wire transfers show an additional £1 million being sent in January 2017 to the London law firm Svetlova LLP, which caters to Russian-speaking and other overseas clients, including those seeking to buy UK property, and which the statement of accounts indicates as the facilitator of the apartment purchase. The money was wired from Adil Global Dis Ticaret Limited Sirketi, a Turkish company with no public record of business activity. Saimaiti said he regularly used such Turkish firms to launder money for the Abdukadyr family and provided documentary evidence.

Who’s Behind Adil Global?

The legal owner of Adil Global could not be reached for comment. His brother, Ismail Kaskariy, spoke briefly with reporters. Kaskariy, a Turkish citizen, said that he personally knew Saimaiti and dined with him on one or two occasions.

The “details of payment” section of the two wire transfer documents indicates the name of Aibibula Nuermaimaiti, linking the mysterious Turkish company to the Abdukadyr family.

All three documents identify the property in question: “262 Wren House.”

UK Land Registry records show that this code refers to a sixth-floor apartment at a posh building on the Strand, an upscale thoroughfare in central London.

The sprawling residential complex opened its doors for its wealthy residents in early 2017 with all of the accoutrements associated with elegant living: a luxury swimming pool, spa, and in-house cinema for occupants, as well as valet parking, a liveried doorman, and a 24-hour concierge — all just a short stroll from the Thames River, the Royal Courts of Justice, and the Royal Opera House.

Saimaiti also gave reporters wire transfer orders indicating that his wife, Wufuli Bumailiyamu, made two additional transfers to Nuermaimaiti’s bank account in the United Kingdom in September 2016.

The two wire-transfer receipts — for £876,105 and £60,000 — were marked with the handwritten note “RK,” an abbreviation Saimaiti said he used for Matraimov. Next to the abbreviation on each document, the word “England” appears to be written in the Uighur language, though there is no mention of an apartment, and the specific purpose of these transfers is unclear.

Raimbek Matraimov’s main connection to London appears to be his son, Bakai Matraimov.

A brochure for the prestigious Bellerbys College in London states that one of its alumni from Kyrgyzstan, identified as “B. Matraimov,” finished studies there in 2017 and moved on to City University’s Cass Business School.

A PR firm representing Bellerbys said “the details of any current or former students” could not be disclosed “for reasons of data protection and privacy.”

According to Bakai Matraimov’s LinkedIn profile, he studied at City University from 2016 to 2019. His mother, Uulkan Turgunova, travelled to London on several occasions, including his 21st birthday, and posted a number of photos from the famously posh Savoy hotel and other upscale establishments.

Money from Third Parties

The millions of pounds Saimaiti wired to the United Kingdom on behalf of the Abdukadyr family highlights the responsibility of legal professionals to monitor whether the funds they receive into their client accounts are from credible sources.

In cases where the sources of private funds for property purchases raise concerns, the UK Legal Sector Affinity Group, which is made up of UK legal sector supervisory authorities and professional bodies, advises legal professionals to ask clients to explain the sources of the funds — and to assess whether those explanations are valid.

“Aborted Transactions” as Money Laundering?

A group of international bar associations has also warned that the client accounts of legal professionals can be abused for money-laundering purposes.

The wire transfers sent to the client account of Svetlova LLP, the firm listed as the facilitator of the purchase of the Wren House apartment, came from a Turkish company with no web presence, no apparent business, and no visible connection to Aibibula Nuermaimaiti, the man whose name appeared in the wire transfer details.

The firm’s owner, solicitor Tatjana Svetlova, did not tell reporters which specific steps, if any, she undertook in relation to the transfers. There is no evidence that Svetlova LLP failed to comply with its legal and professional responsibilities. In response to inquiries from reporters, she wrote that her firm “fully complies with all legal and regulatory requirements, including in relation to anti money laundering/[know-your-client]/source of funds,” and that “all relevant information is made available to regulatory and law enforcement agencies upon request.”

She wrote that she and her colleagues had never previously heard of Saimaiti or his murder.

Svetlova wrote that confidentiality requirements prevented her from confirming the identities of her firm’s clients or its work on their behalf.

“It is therefore not possible for us to comment on your questions or provide detailed rebuttals,” she wrote, adding that “no negative inference should be drawn by the professional constraints under which we are required to operate.”

Svetlova wrote that any allegation that her firm “was involved in either the laundering of money obtained from criminal activity in Central Asia and/or knowingly enabled a wealthy Uyghur family to bribe a senior Kyrgyz customs official” would be “entirely false.”

“A Buyer Who Asked That the Toilets Be Changed”

What happened to the money wired to the UK for the Wren House apartment — whether it was refunded, transferred to someone else, or used to buy another property — remains unclear.

What is clear is that the apartment indicated in the wire transfers was ultimately purchased by someone with no apparent links to either the Abdukadyr or Matraimov families.

The apartment was acquired on May 19, 2017 by the former wife of a wealthy Russian businessman. That was about four months after the Saimaiti wire transfers were sent to the Svetlova LLP client account.

The current owner purchased the apartment through an offshore entity for £5.3 million, close to the amount indicated in the document Saimaiti provided.

She said in an interview that she purchased the apartment directly from the developer, Berkeley Group. She said she was told at the time that the apartment had a previous prospective buyer who ultimately declined to go through with the purchase.

During her viewing of the apartment, “they told me that it had just appeared on the market because there had already been a buyer who asked that the toilets be changed” to include a bidet function, the owner told reporters.

“As you understand, Berkeley would not make any changes without money. As far as I recall, the buyer declined because he found a better option, but I don’t know if it was with Berkeley or some other company,” she said.

She added that she had no idea who the previous prospective buyer was.

“I didn’t really ask around. I simply didn’t have a reason to. Furthermore, even if I had asked, it’s unlikely they would have told me the name of the buyer and the reason he declined. These are always confidential issues,” she said.

Asked whether she had ever worked with Svetlova LLP, the new owner responded: “I have never even heard of that firm.”

Berkeley Group CEO Rob Perrins, who owns a £2.1 million apartment on the fourth floor of Wren House, did not respond to emails seeking comment about the documents provided by Saimaiti or a potential prospective buyer who appears to have pulled out of an agreement to buy Apartment 262.

In response to the e-mailed inquiries, Berkeley Group solicitor Joanna McClelland wrote: “We do not comment on buyers or prospective buyers.”