Beginning in 2013, if an investor from outside the European Union wanted to live in Hungary, they had to buy a special state bond from one of eight companies with exclusive rights to sell them on behalf of the government.

And it wasn’t cheap: the bonds initially cost €250,000; the price later jumped to €300,000.

That Golden Visa-style program was suspended in 2017 after public criticism erupted over the bondsellers’ opacity. Nobody knew who owned most of the companies — seven of the eight were anonymously registered in offshore tax havens, making it impossible to know who pocketed the profits.

And these were considerable — the eight companies pulled in at least US$ 600 million in fees during the four years the program was in operation, based on calculations by g7.hu.

Now an investigation by reporters for g7, a business and economics news portal, reveals that the way those companies were chosen may have violated Hungarian law.

Hungary’s Central Bank is normally responsible for overseeing and licensing financial institutions, including those that buy and sell stocks and bonds, and would have been the logical choice to select and regulate companies to sell the bonds to residency applicants. But in this case, the Economic Committee of the Hungarian Parliament took over the oversight.

Over seven years, that committee’s work was marred by a pattern of failing to follow procedures, making decisions on incomplete information, secretive processes, and in some cases, potential illegal activities.

In Hungary, parliamentary bodies and members of Parliament cannot be held legally responsible for such decisions. For example, MPs cannot be jailed because of votes they take, nor can the Economic Committee be sued. Hungary’s courts can only intervene if the committee denies a request for information of public interest.

With the help of Transparency International Hungary (TIH), a reporter for g7.hu did sue. The action targeted the State Debt Management Company — the only agency with the power to issue and trade in state bonds — and the Parliament’s Economic Committee. Citing “freedom of information” grounds, the reporter sought documents showing how the Golden Visa businesses were created and how many bond packages they sold. The case was brought before Budapest’s Metropolitan Tribunal.

The reporter and TI-Hungary ultimately obtained the companies’ founding documents, their applications for permission to trade in state bonds, and information on the appointment of company representatives.

Rules? What Rules?

By comparing the documents with minutes of the Economic Committee’s meetings, g7.hu found the committee’s chairman repeatedly neglected to show the full committee all the information required by law.

The law regulating residency bonds clearly states that every application must be presented to the full committee and voted on by its members.

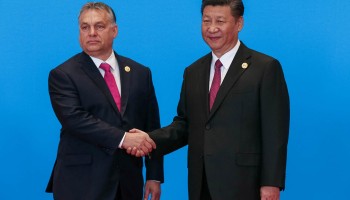

Two chairmen headed the committee over the four years the Golden Visa program operated. Antal Rogan was the first, serving from April 2010 until October 2015, when he was appointed head of Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s cabinet. He was succeeded by Erik Banki. Both men gave only limited information to committee members, sharing some documents and withholding others.

Opposition party members on the 15-member committee told reporters they had little idea what was happening, a situation apparently enabled by the fact that a two-thirds majority was held by members of Orban’s ruling Fidesz party. Committee documents obtained by reporters include correspondence between its chairman and the bond-selling companies, answering their questions or requesting additional information as necessary.

This secrecy was a recurring theme.

Under the bond program, companies were assigned territories around the world, each given a monopoly to sell bonds in a specific region. In two instances, however, it appears that companies that were initially granted a region were shoved aside by the committee so another company could take over.

From the beginning, the bond program seemed designed to benefit insiders. The opportunity to sell bonds was never advertised, so companies that applied must have had prior knowledge of the opportunity. These companies applied either via an email address on the Economic Committee website or by sending applications by mail to the official address of the Hungarian Parliament. According to the law, all applications should have been listed on the committee’s agenda, but records show this did not always happen.

Farewell to Euro-Asia

The case of a Singapore-registered firm called Euro-Asia Investment Management Ltd. is an illuminating example.

Paperwork shows Euro-Asia first applied to handle Hungarian state bonds for Singaporean and Thai citizens on May 3, 2013, while Rogan was still the committee’s chairman.

That request was ultimately approved at its June 10 meeting that year, but only for Singapore. Documents indicate Euro-Asia’s desire to sell to Thai citizens was never put before the full committee, although the company never withdrew the request.

Later, Euro-Asia applied to expand its sales area to include Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Armenia, Malaysia, Indonesia, India, and Iran, but based on committee minutes, the full panel was never presented with the application and never considered it.

Things only got worse for Euro-Asia, which ultimately lost its permit to sell residency bonds on Dec. 15, 2015, in what appears to be an arbitrary decision that may have violated the law. The Economic Committee cited “insufficient activity” as the reason, noting that the bondsmen were required to sell at least 100 bonds in three years to maintain their licenses. Euro-Asia hadn’t yet been selling bonds for three years. The company had successfully sold 42 bonds by the end of 2015, about the time the Economic Committee revoked its license.

A second company, Discus Holding Ltd., got virtually the same treatment on the same day and for the same reason, losing its permit to sell in South Africa, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Nigeria, the U.S., Singapore and Thailand. Discus had sold 36 bonds.

The timing is interesting. Days before the two firms lost their permits, Arton Capital Hungary, a limited liability company incorporated in Hungary, applied to sell bonds in several of the same countries (namely Singapore, Indonesia, Nigeria, Thailand, the U.S., and Kazakhstan) that Euro-Asia and Discus had been handling. However, Arton’s initial application did not appear on the Economic Committee agendas obtained by reporters or those posted by the committee. On Jan. 7, Arton Capital re-applied, and was granted the licenses in February 2016.

Arton Capital Hungary is the local branch of a global citizenship-by-investment services company. Of the eight intermediaries registered in Hungary to sell residency bonds, Arton was the only one whose owners were a matter of public record. It was ultimately granted the right to sell Hungary’s residency bonds all over the world — the only company awarded that right.

Spokespeople for the Economic Committee did not respond to repeated questions regarding why territories managed by Euro-Asia and Discus were transferred to Arton Capital. Arton Capital also did not reply to requests for comment.

When Evidence Goes Awry

One curious coincidence involves the intermediary that sold the most bonds: the Hungary State Special Debt Fund (HSSDF), which was established in the Cayman Islands, a British offshore tax haven, on Oct. 26, 2012.

The very next day, Economic Committee Chairman Rogan proposed the bond program to Parliament.

Once the HSSDF had obtained its license to sell bonds, it sold the license to the similarly named Hungary State Special Debt Management Company (HSSDM), registered in Hong Kong.

The Hong Kong company is owned by three enterprises registered in the British Virgin Islands (BVI): Star Wealth Ltd., 25 percent; Prime Ally Ltd., 30 percent; and Ace Deal Investments Ltd, 45 percent.

Prime Ally Ltd. had been established in the BVI on Oct. 26, the same day as the HSSDF — the other two enterprises were set up a few days later.

There were other apparent violations.

Josef Hermann, director and owner of the Liechtenstein-registered Voldan Investments Ltd., submitted an application on Dec. 12, 2015, to represent the residency bond program in South Africa, Kenya, Azerbaijan, Austria and Turkey, but this request was never presented to the committee. Bela Schonek, Voldan’s attorney, also never submitted documents proving he had a legal power of attorney to represent Voldan. (In May 2013, Voldan applied for and succeeded in getting a permit to sell Hungarian government bonds in a number of eastern European and post-Soviet countries).

Another Cyprus-registered company, Innozone Holding Ltd., was supposed to attach four documents to its application on April 16, 2013: a record of its corporate charter in Cyprus, Cypriot registry records referring to the company, and the official Hungarian translations of both.

However, there is no record of the original documents, which would indicate that the committee assessed the company’s application without all the required evidence.

The Story Was in the Documents

Miklos Ligeti, the legal director of Transparency International Hungary, filed a formal criminal complaint with the police of Budapest’s Fifth District on Jan. 30, alleging abuse of authority and illicit concealment of public information.

Ligeti said the evidence shows that the committee approved permits for selling residency bonds based on incomplete data and documents.

And while the committee itself cannot be sued, Legeti says that under Hungary’s criminal code, committee members are considered public officials and the committee’s irregular procedures may have constituted a breach of official duties or the misuse of official positions.

On March 13, the police told Transparency International Hungary they had forwarded the complaint to the Central Office of Prosecutorial Investigations, the section of Hungary’s Prosecution Service with exclusive jurisdiction to investigate suspected offenses of persons with immunity, such as members of Parliament.

Editor’s note: Since this story was written, Direkt36 has reported that Hungary’s suspended Golden Visa program may have returned in a new, cheaper version, although the government has made no official announcement. Shortly after the April 8 landslide victory of the governing Fidesz party in Hungary’s parliamentary election, an ad appeared on Chinese social media touting a new immigration program in Hungary, posted by LSP International Ltd., a company based in Hong Kong.

The new scheme, called Home Purchase Immigration, offers a Hungarian residence permit in exchange for investing at least 25 million Hungarian forints (€78,000) in Hungarian real estate and paying €50,000 in fees. The company advertising the new scheme is owned by Lian Wang, a Chinese businessman who also participated in Hungary’s highly controversial residency bond program, which was suspended last year amid allegations of corruption and security risks.

The Chinese company says it has negotiated the deal with the Hungarian Immigration Office. However that office, and the Government Information Center, say no such deal has been struck.

This story was produced as part of the Global Anti-Corruption Consortium, a partnership between OCCRP and Transparency International.