Reported by

When John met doctor Iuliu Stan at a British public hospital, he was in agony. With a lacerated finger and a dislocated shoulder after being attacked on a night out, John remembers how Stan was called by a nurse to help him manage his pain as he awaited surgery. But he says what happened next changed his life.

Stan, who was a junior doctor in trauma and orthopedics at the Royal Cornwall Hospital in southwest England, told John that he needed to administer the pain medication as a suppository, meaning that it had to be inserted rectally. “I sort of asked him, is there another way? You know, is there any other kind of medication that I can take? And he said, ‘No, I have to do it this way,’” said John, who is using a pseudonym. “He's a doctor in a hospital, and you're supposed to kind of trust what they say.”

Afterwards he mentioned to a friend that the experience hadn’t felt right, but then tried to bury it. “I didn't want to think about it,” John recalled. “I felt really ashamed. Like I had done something wrong.”

Back then in 2019, when John was in his 20s, he didn’t yet know that he had become the victim of a doctor who a British medical tribunal has since found systematically targeted young men and children in his care during his five-year stint in Cornwall between 2015 and 2020.

Last year, the U.K.’s Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service struck Stan off the medical register for misconduct after finding that he had “subjected patients to unnecessary, invasive and intimate procedures for his own sexual gratification.” He administered pain relief medication and laxatives rectally 277 times to male patients, and once to a female patient, over a five-year period. Experts told the tribunal it was unusual for a doctor, rather than nursing staff, to administer such medication, noting that Stan had sometimes abused the same patient multiple times.

The tribunal report concluded that removing him from Britain’s medical register was “the only means of protecting patients.”

But Stan is still working as a doctor — just on the other side of Europe.

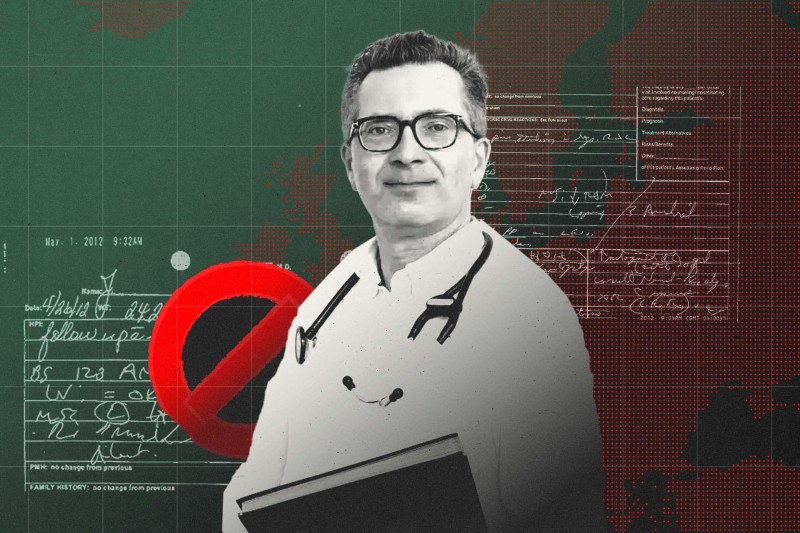

The 43-year-old returned to his native Romania in 2021, where he has a medical license and works as a trauma and orthopedic specialist at the County Emergency Hospital in the city of Cluj-Napoca.

Stan denied to a reporter from OCCRP’s Romanian partner Public Record that he had sexually abused his U.K. patients. “Everything I did, I did in the interests of the patients, to the best of my ability,” he said.

“None of the patients complained about me. On the contrary, they were satisfied and congratulated me.”

The County Emergency Hospital in Cluj-Napoca, Romania.

A new investigation by OCCRP and partners across Europe found that doctors like Stan, who have been banned in one country, can easily relocate and practice again in another due to ineffective information-sharing between states and a lack of response by some authorities to bans outside their own jurisdictions.

OCCRP confirmed that over 100 doctors who are currently banned or suspended from practicing medicine in one or more countries for a range of serious reasons — including cases of sexual assaults during their medical work, botched medical treatments and inserting breast implants without consent — are licensed to practice elsewhere.

By calling their new workplaces, making online appointments, or visiting their practices in person, reporters confirmed that the majority of those doctors were not only still licensed, but actively practicing medicine.

Some of them relocated to a country where they already had a license, while others managed to obtain new licenses.

And the findings are just the tip of the iceberg, with the true scope of the problem hidden by a lack of complete and comparable data, reporters found.

After receiving questions from OCCRP and its partners, regulatory authorities in the U.K., Germany, Cyprus, Spain, and Norway have confirmed that they are investigating individual doctors practicing in their jurisdictions.

Britain’s health secretary Wes Streeting told OCCRP’s U.K. partner The Times that he had ordered “urgent clarification” from the country’s General Medical Council about its vetting processes for international doctors, after The Times identified 22 doctors in the U.K. who had been subject to discipline or restrictions overseas with no record of it showing on their licenses.

In Iuliu Stan’s case, the General Medical Council said it had notified the Romanian medical regulator in March 2024 that he had been removed from the U.K. register. Media in Romania have also reported on his abuse of patients in England. But he is still permitted to practice in Romania.

Romanian online media ziare.com reported in February 2024 on doctor Iuliu Stan's U.K. ban over patient abuse claims.

The head of the regional body that supervises doctors in Cluj-Napoca, Ion Cosmin Puia, claimed Stan had not had a proper chance to defend himself in the U.K. and that the ban was not relevant in Romania because the U.K. is outside the European Union.

“We have no investigations to carry out here concerning what happened I don’t know how long ago in the United Kingdom,” Puia told Public Record.

“I don’t know how things are done in the United Kingdom, and therefore there is no point in discussing it. Anyway, that is not within our competence. Yes, Dr. Stan has the right to practice medicine in Romania. I can tell you that, so far, in Romania he has behaved absolutely without problems.”

Romania’s College of Physicians, which approves doctors’ licenses nationally, said that neither it nor the local Cluj-Napoca branch were in a legal position to ban a doctor based on a decision made in the U.K., and that there had been no disciplinary, civil, or criminal proceedings in Romania that would justify it.

Stan was not present at the tribunal hearings in the U.K. and had disengaged from the process, according to the decision to erase him from the British register last year.

John was told in a letter by the Royal Cornwall Hospitals Trust in July 2024 that Stan had been struck off – it noted that he had been given rectal medication by the doctor and said it was “deeply sorry for the distress caused by this doctor’s professional misconduct.” The trust said in the letter that it was working with police who had opened a criminal investigation.

John, using a pseudonym to protect his identity, spoke to OCCRP about his experiences as a patient of Iuliu Stan.

“It was really difficult when I got the letter because everything felt like it started to spiral,” said John, who had to take time off work and couldn’t sleep. But he also felt relief that Stan was no longer able to practice in the U.K.. Learning that he was still working as a doctor in Romania left John “incredibly angry.”

“The fact that someone who has negatively impacted so many lives with their behavior when they were in a position of care over those people, and myself being one of them, has then been allowed to keep practicing and potentially harm more people is abhorrent,” he said.

“It makes it feel like the people in charge don't care and that they think nothing of the people that have already been his victims."

The County Emergency Hospital in Cluj-Napoca, where Stan now works, did not respond to requests for comment.

Devon and Cornwall police told OCCRP that they were investigating reports of sexual assault at the Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust. “The investigation is complex and is expected to last a number of months,” police said, without providing further detail.

Information Hidden From The Public

Most countries investigated by reporters did not publish data on whether doctors had ever had their licenses suspended or revoked, making it difficult for members of the public and journalists to see whether they had ever faced disciplinary action.

When journalists asked for that information by sending freedom-of-information requests to national licensing authorities, they were often rejected for privacy reasons.

Information-sharing across borders was erratic and, as with the case of Stan, notifications about bans for serious offenses did not necessarily affect a doctor’s ability to practice elsewhere.

In most cases reporters did not find allegations had been brought against banned doctors after they relocated, but the investigation raises questions over how medics who have lost their licenses for serious offenses, including patient harm, can so easily pick up their careers in another country.

Reporters focused on doctors working in Europe, but found that the problem extended beyond regional borders, with some doctors moving to other continents following a ban.

Connecting the Dots: How We Traced Banned Doctors Across Jurisdictions

With public data scarce on doctors' licenses and bans, OCCRP built a database to generate leads for reporters.

There is an information exchange system that covers the 30 countries of the European Union and the wider European Economic Area, but full details about which doctors had been listed as suspended or banned via this system were not made transparent to reporters.

Member states are required to file alerts about suspensions and bans on doctors and other qualified professionals in their own jurisdictions to that online tool, which is called the Internal Market Information System (IMI) and is designed for collaboration between national authorities to protect public health and safety. But when reporters requested the alert history for doctors, they found that some countries had rarely or never sent one.

Even in cases in which reporters were able to verify that an alert had been sent about a ban on a doctor in one country, either via the IMI or another route, it did not necessarily lead to action by the doctor’s current jurisdiction. Member states are not obliged to consult the IMI alert system before approving a doctor’s qualifications, and have differing revocation standards.

Sjur Lehmann, who used to work as a doctor and is now head of Norway’s board of health supervision, said that when healthcare workers are able to move freely from one country to another, the need for authorities to cooperate increases.

“If a doctor loses their license for abuse or for otherwise putting patients at risk, then they will be just as dangerous in another country. So if we do not have a system in place for following up and cooperating in such situations, then in the worst case scenario, new patients will continue to be exposed to the same,” he told OCCRP’s Norwegian partner VG.

Commenting on the current system in Europe, he added: “The system we have today is better than no system at all, but there are clearly sides to it that can — and should — be further developed and improved.”

Head of Norway’s board of health supervision, Sjur Lehmann.

Tom Goffin, a professor of healthcare law at Ghent University in Belgium, said the IMI warning system made little difference in practice because it wasn't primarily established to prevent malpractice in healthcare and healthcare providers are only a small part of it. The system is based on the principle of free movement of goods, services, and people within the EU, he told OCCRP’s Belgian partner De Tijd.

"The reports about healthcare providers who are in breach don't amount to much either,” he added. “Member states are asked to report their identity and the duration of their sanction. But more details aren't required. In most cases, we have no idea what someone did wrong or why they are no longer allowed to practice their profession."

Action Against Medical Accidents, a British charity that advocates for patient safety and justice, said regulators and employers must have “foolproof systems” for detecting doctors crossing borders to avoid bans or restrictions.

“Public trust in the regulation of medical staff is vital and it is deeply worrying that some doctors are managing to move country and continue to treat patients,” said the charity’s chief executive, Paul Whiteing.

Questions Raised Over European Alert System

The majority of the countries investigated by reporters belong to the European Union or European Economic Area.

Although there is a system for automatic recognition of professional qualifications for doctors moving within the EU and EEA , they must still apply to authorities in the country where they want to work in order to get a license to practice there.

It is mandatory for member states to send alerts about doctors whose professional activities have been restricted or prohibited, even temporarily, by national authorities or the courts via the commission’s Internal Market Information system, or IMI. But reporters found the alert system was barely or never used by some countries in relation to disciplinary actions against doctors.

A notification about an alert is automatically sent out by email to authorities in EU and EEA countries, who can review it within the IMI portal.

OCCRP asked the European Commission for copies of all alerts and email notifications that had been sent out about restrictions and prohibitions on doctors between 2016 and July 2025 and received more than 17,000 results.

The list the commission sent to reporters was anonymized, containing only case numbers, not doctors’ names, but it did include dates of restrictions and prohibitions. Reporters were able to use that anonymized data to find likely matches according to dates of license revocations given, and to lodge freedom-of-information requests with national authorities requesting the name of the doctor involved.

However, the data also revealed that some countries had never filed an IMI alert since the alert system came into force in 2016.

Malta, Estonia, Greece, and Lichtenstein sent no IMI alerts about a doctor from 2016 to 2025, and 10 other countries filed fewer than 10 alerts each during that time period.

The European Commission said it was “monitoring the situation concerning the fulfilment of the obligation by member states to send alerts via IMI” and that it may start infringement procedures if there is evidence that states are not fulfilling their obligations. It confirmed that infringement proceedings are currently in place against Greece.

In some countries, the lack of alerts to IMI reflected the infrequency of license revocations nationally – Malta, for example, has never revoked a doctor’s license.

In Slovenia, which has only sent one IMI alert about a doctor since 2016, only five doctors have been suspended in the past 20 years and none has been permanently banned, the national Medical Chamber told reporters in an email.

The Chamber refused to disclose the reasons for these suspensions, claiming that it considers them personal data of doctors. After reporters complained about the heavily redacted revocation decisions given by the Chamber in response to their FOI requests, which concealed the reasons for the doctors’ suspensions, the national freedom-of-information authority decided that access should be granted in the public interest. However, the Chamber countered the decision in a lawsuit which is still ongoing.

Questions have been raised over fundamental flaws within the IMI alert system and recognition of professional qualifications in general. A report last year by the European Court of Auditors found that national authorities were “overwhelmed by alerts” and did not check them when reviewing applications for recognition of professional qualifications, nor was it mandatory for them to do so.

It also pointed out that although member states were obliged to send out IMI alerts indicating “substantial reasons” for a warning, there was no formal definition of a “substantial reason,” and countries could decide what to include.

The report recommended that “substantial reasons” be defined, and that countries should be obliged to consult the alert system during the recognition process.

In a written response to the report, the European Commission promised to provide more context to help member states to distinguish cases that needed following up, including clarifying the concept of “substantial reasons” by 2025. It also agreed to provide guidance and “facilitate the exchange of best practice on the follow up of alerts,” but noted that the legal consequences of the alerts are up to member states.

The Commission told OCCRP that it was still working on a guidance document including addressing the “substantial reasons” question that would be released before the end of the year as well as improving on the “user friendliness" of IMI alerts.

“The IMI alert system only has a supportive role for member states, which are responsible for identifying the cases on their territory where doctors are unfit to pursue their profession and to apply relevant measures (such as prohibition or restriction),” the Commission said.

Members of the EU 's parliament have been questioning the effectiveness of the IMI system and countries’ use of it since 2009.

A European Commission memorandum from 2020 said that member states had been slow to start using the alert system, and had found difficulties including how to filter the most relevant alerts from the high volume they received.

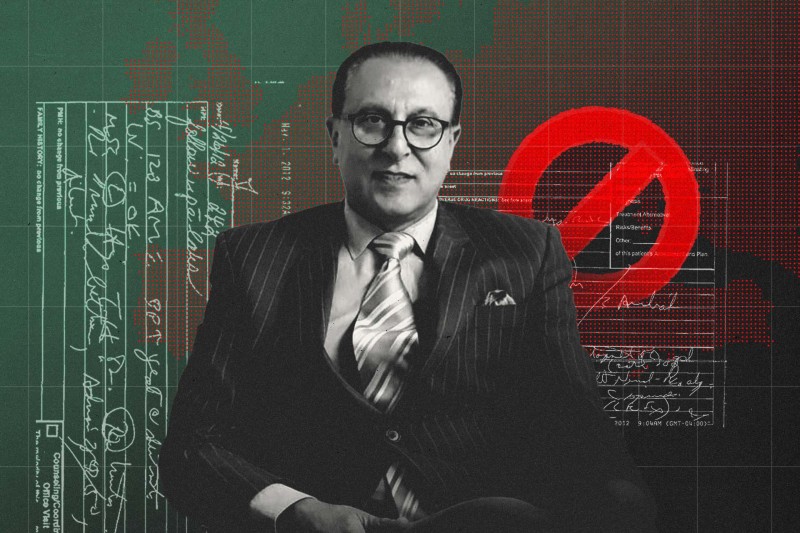

“It would be better for everybody if the system would be user friendly so people would feed and use it,” said Stef Blok, a former Dutch economics minister who is a member of the European Court of Auditors and oversaw the 2024 report.

“Can you point specifically to mistakes or accidents that have happened because of the low use in a number of countries? You cannot, but the likelihood is higher,” he told OCCRP’s Dutch partner Investico.

Former Dutch economics minister and member of the European Court of Auditors, Stef Blok.

Countries outside the EEA do not have access to the alerts. The president of the Swiss Medical Association, Yvonne Gilli, said: “Networking with the EU's warning system would be a huge help in combating the problem,” adding that otherwise Switzerland could become a destination for doctors who should no longer be practicing. “People with a certain criminal energy go where there are gaps in the system,” she said.

Despite the U.K. leaving the EU and the EEA in 2020, its General Medical Council said it still notifies overseas regulators when a doctor on the U.K. register has received a sanction, and informs the U.S.-based International Association of Medical Regulatory Authorities (IAMRA), which hosts an online information exchange for medical regulators.

IAMRA told OCCRP that there are currently seven Medical Regulatory Authorities submitting notifications including from Australia, New Zealand, and the U.K., and several U.S. state regulators. All IAMRA members have access to and are encouraged to use its information-sharing platform, IAMRA said.

Banned in the U.K. and Netherlands, Practicing in Germany

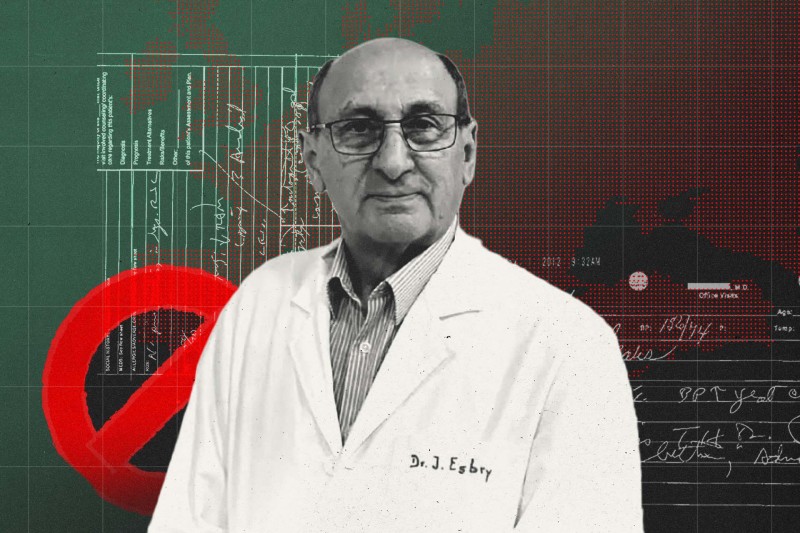

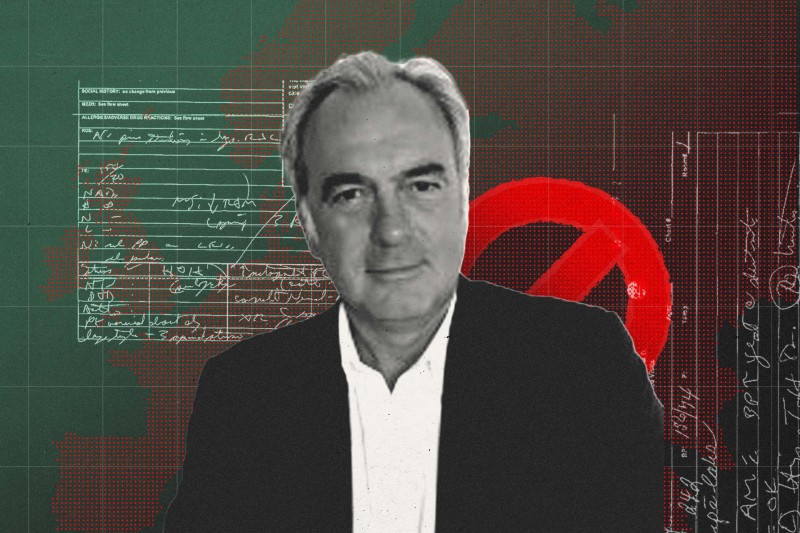

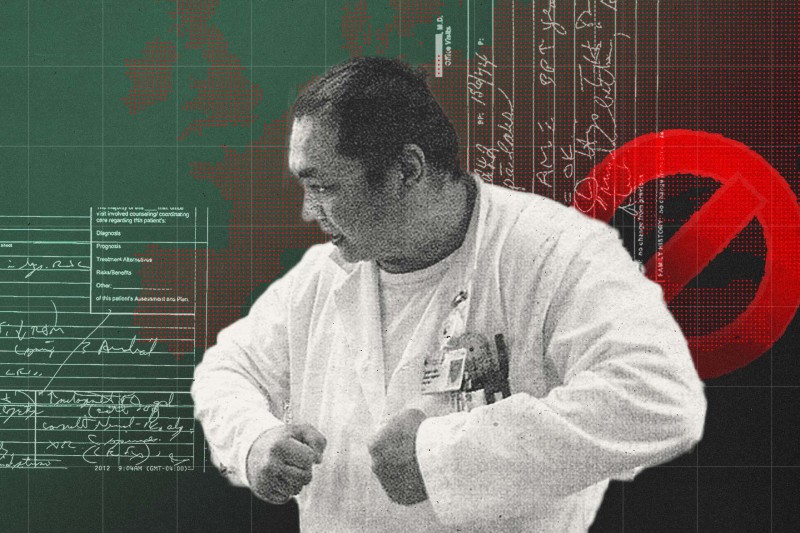

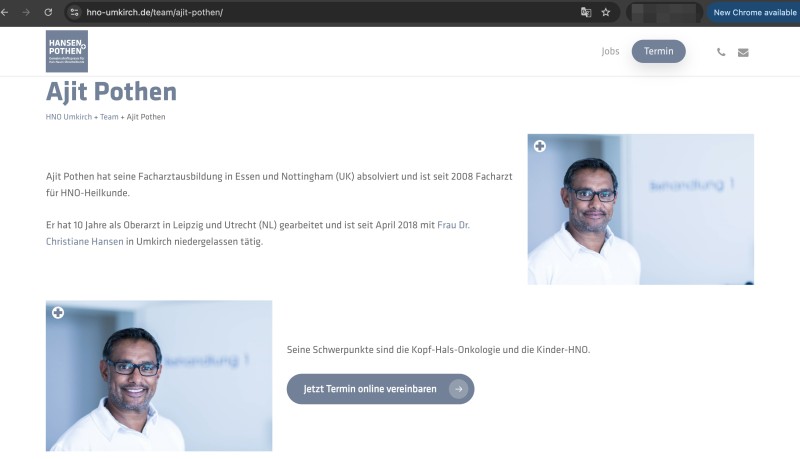

The daughters of Denise Barnes say it is hard to believe that Ajit Pothen, a doctor who was struck off the British medical register in 2021 after discharging their mother from the hospital when she was seriously unwell, is still licensed and treating patients in Germany.

Pothen also lost his license in the Netherlands in 2022, following the U.K. ban. However, he still has a medical license in Germany, where he has co-owned a practice since 2018.

Alongside a smiling photo on the website for the clinic that Pothen co-runs in the southern German town of Umkirch, he is described as focusing on pediatric ear, nose and throat patients, as well as head and neck oncology.

Ajit Pothen's professional profile on the website of the clinic that he co-runs in Umkirch, Germany.

“I feel very, very angry. I can't believe that he's actually working again,” Denise’s daughter Nicola Bradley told reporters from OCCRP’s German partner ZDF.

Denise, who was 67, had been suffering from respiratory problems for months before her condition suddenly deteriorated and her family called emergency services.

Consultant Pothen examined Denise – who had been diagnosed with a range of conditions – at the Queen’s Medical Center hospital in the British city of Nottingham, but discharged her the same day. He later testified at a coroner’s inquest that he had planned further scans at an appointment six days later.

But Denise’s breathing difficulties quickly resumed and her family urged her to go back to the hospital, recalling how she was hanging her head out of the car window to get air on the journey home.

Denise died that night, in February 2017.

The U.K.’s Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service found that Pothen had failed to recognize the seriousness of Denise’s condition. A coroner’s inquest into her death found that she had died from pneumonia and multiple system atrophy, and noted that she had been inappropriately discharged from hospital and would likely not have died if she had been kept on oxygen and monitored.

In its decision to strike him off the British medical register, the U.K. tribunal found that in his treatment of Denise Barnes he “had failed to maintain the necessary standards, which in his case fell considerably short of what is expected of a doctor.”

Denise’s daughter holding a portrait of her mother.

A lawyer representing Pothen said the doctor “extends his sympathy” to the family, but that “the deceased was not autopsied, and therefore there are no factual findings regarding the cause of death.”

He added that his bans in the U.K. and the Netherlands had no impact on his license in Germany. The lawyer said Pothen had initially been unaware that he had been removed from the U.K. register and that he had not been involved in those proceedings.

Pothen had been on his first shift as an ear, nose and throat consultant at QMC, a teaching hospital within the U.K.’s public National Health System, when he examined Denise. He had been hired as a temporary consultant there after a stint working at UMC Utrecht hospital in the Netherlands.

During his time at UMC Utrecht, he had offered substandard care to four patients, including two who had subsequently died, according to a report from the Dutch inspectorate in April 2017. However, those incidents did not result in a ban against him at the time.

A Dutch inspectorate report noted that Pothen had informed his “foreign” employer about the investigation into him. But the U.K. medical tribunal that banned him in 2021 found he had not been fully honest, failing to mention he had been suspended by the Dutch hospital for seven months.

Pothen’s lawyer said the cases in the Netherlands had been reported and investigated, and had not resulted in professional consequences for him, adding that his suspension during that time was "purely routine." He said that Pothen does not carry out surgical procedures in his current private practice in Germany and that there had been no cause for complaint since he started working there.

The lawyer also said Pothen had downplayed the Dutch investigation when applying for the Nottingham job due to personal circumstances at the time, and accepted that this had “jeopardized” his U.K. license.

Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust did not answer questions from OCCRP’s U.K. partner The Times about what measures it had taken to check with his previous employers about any concerns over his practice and why it had employed him at a time when he was under investigation in the Netherlands.

Pothen’s case also illustrates gaps in medical oversight, where disciplinary proceedings in one European country do not prevent a doctor from practicing in another and patients are left in the dark about their doctor’s record abroad.

Britain’s General Medical Council sent a notification to German regional authorities when Pothen’s license was revoked, but it is not clear whether the notification was received by the region in which he currently works.

In the anonymized IMI alert data sent to OCCRP by the European Commission, reporters found an alert had been sent by the Netherlands about a doctor being prohibited from practicing on the same date as Pothen’s license was revoked there in January 2022.

The Stuttgart Regional Council, the licensing authority responsible for Pothen, did not respond to detailed questions about whether it was aware of Pothen’s bans in the U.K. and Netherlands or how it had responded to that information. “Of course, we take your inquiry and the associated information, as well as all information we receive, seriously…However, we are not able to make any personal statements regarding professional reviews,” the council said.

For the Barnes family, the pain of Denise’s death still runs deep.

“At the end of the day, she would have and should have still been here,” Nicola said. “I don't think he should be practicing anywhere, not in any country.”

Denise Barnes' daughters looking at a family photo album.

Victims Seek Justice

Two lawyers who are representing victims of Romanian doctor Iuliu Stan in civil compensation claims against the Royal Cornwall Hospitals Trust called for stronger cross-border collaboration to safeguard the public.

Solicitor Gary Walker of British firm Enable Law is representing 40 victims and said there should be an “urgent review” of international systems through which medical regulators share information on disciplinary action and criminal sanctions. He said it was “shocking and deeply upsetting” for people affected by Stan to learn that he is treating patients in Romania.

There has to be a baseline and a basic standard of care that would prevent doctors working elsewhere.

Tom Fletcher, U.K.-based lawyer representing victims of Dr. Iuliu Stan.

Lawyer Tom Fletcher, a partner at Irwin Mitchell law firm and a specialist in abuse cases, is representing John and other victims of Iuliu Stan.

Fletcher said that if a doctor had been struck off in one jurisdiction for sexual abuse, they should not be able to work as a doctor in another country. “There has to be a baseline and a basic standard of care that would prevent doctors working elsewhere,” he said.

He described how Stan’s actions had long-term impact on victims, affecting their relationships and their ability to work. It has also discouraged them from seeking medical help when they need it, he said.

“What underpins all of this is that lack of trust and that fear of seeking medical treatment and how debilitating that can be and how dangerous that can be for for individuals who are in need of of basic medical care,” he told OCCRP.

John described how building back that trust was a long and painful process.

“As a patient, you are forced to put your trust in people. You don't really get a choice. You were taught from a very young age that you go to a hospital and they will help you. Sadly, that's not always the case. And it can be very difficult to regain that trust once it's broken,” he said.

He added that he was motivated to speak out about his own experience because he worries that other victims, particularly younger ones, might be suffering in silence.

“I'm ashamed of what happened. Part of me still blames myself for it. And there are people out there that might feel the same way, but they don't have to. They need to know that they're not alone. They need to understand that there are people who can be supportive and help,” he said.

Clarification: This article has been updated to clarify that notifications made to the International Association of Medical Regulatory Authorities (IAMRA) are available to all of its members.