Reported by

OCCRP’s Research and Data Team started working on the 'Bad Practice' project in May 2025, after discussions with colleagues from several European countries. They had noticed that it was surprisingly easy for doctors who committed serious offenses to simply relocate and start practicing medicine again. We decided to build a database and see if we could understand the scale of the problem in practice.

To make our task easier, we focused on countries in and around Europe. The continent is supposed to be less vulnerable to jurisdiction-hopping doctors since EU countries share information about medical licenses and suspensions — at least theoretically.

But we quickly ran into a major problem: In order to build a database, you need data.

We had set out to gather two data sets from every country: All the licensed doctors, and all doctors who had been formally reprimanded, or lost their licenses. With this information, we would be able to determine whether doctors banned in one country were licensed in another. But this was far easier said than done.

A few countries maintain well-structured, searchable registries of doctors publicly available for download, through regulatory bodies or national medical associations. But others offer only partial or poorly organized access, requiring us to build what’s known as a scraper to extract it. (Scraping a website refers to automatically loading its pages to extract the data.) In some countries, like Spain and Austria, data on doctors is available only by region, not centrally, so we had to set up multiple scrapers.

In other places, there is no public register at all, with licensing data kept by authorities but not shared openly.

Almost every country required a completely different approach — and even within countries, lists of doctors and data on disciplinary actions against them were often in different places. Disciplinary data tended to be far less accessible to the public.

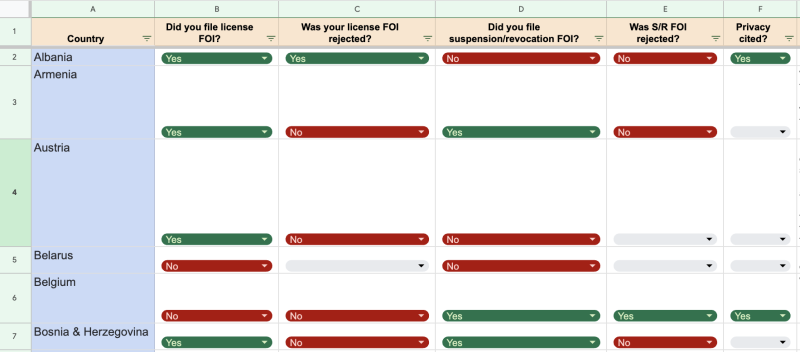

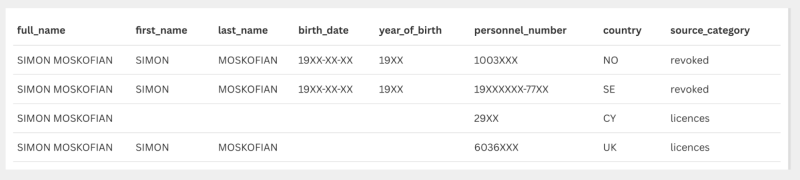

In countries where it wasn’t possible to collect data by scraping — either because data on doctors was completely unavailable online, or because it was impossible to scrape — reporters filed freedom-of-information requests to obtain it. Our group made a huge coordinated effort and filed dozens of requests for data in countries around Europe. Authorities in 17 countries, including Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland, ended up providing journalists with some data on licensed doctors, and/or those whose licenses had been revoked or suspended.

A snapshot of our shared FOIA tracker, so we could keep track of requests we submitted.

But many of the requests for information were denied for privacy reasons. In these cases, we had to get creative. In Germany, we used a commercial website to find the names of practicing doctors. In France, where the national body rejected our freedom-of-information request, we drew on media articles to build a small dataset of doctors whose licenses had been revoked. (We confirmed all cases using court records before writing about them.) In Italy, we did something similar using court cases involving doctors.

In total, we’ve now built 42 scrapers, and obtained data from 51 countries and regions, allowing us to download over 2.5 million records. (A record refers to a line of data — it might be a disciplinary action, an administrative change, or a license).

Despite all this work, the data we gathered is still far from perfect. For example, we obtained many more records for licensed doctors than for license revocations. Still, it was a good start and gave us confidence that we’d be able to move forward with our project. But we quickly ran into another problem: The data was not consistent.

The Great Clean-Up

Even within the EU, information about doctors was recorded in an astounding variety of ways.

Names are ordered differently in different countries, and sometimes have different mandatory components (for example, patronymics); dates can be written in different formats; and medical specialties are grouped differently across countries.

In some countries, information like birthdates — which are crucial for identifying people, especially when their names are common — didn’t even exist in records of doctors. Professional information, like when the doctors graduated from medical school and received their licenses, was also frequently missing.

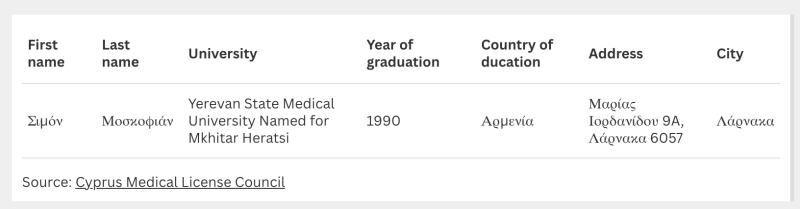

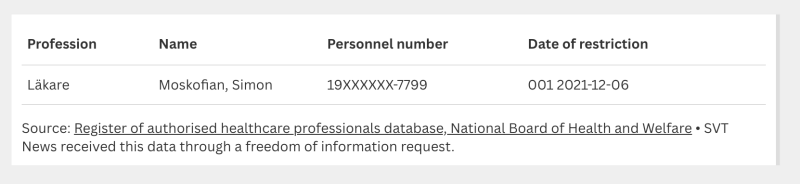

Here’s one example. One doctor we’ve been investigating appeared in our original datasets like this (We’ve anonymized some of his personal information for privacy reasons):

It would be impossible for our database to even recognize this as the same person.

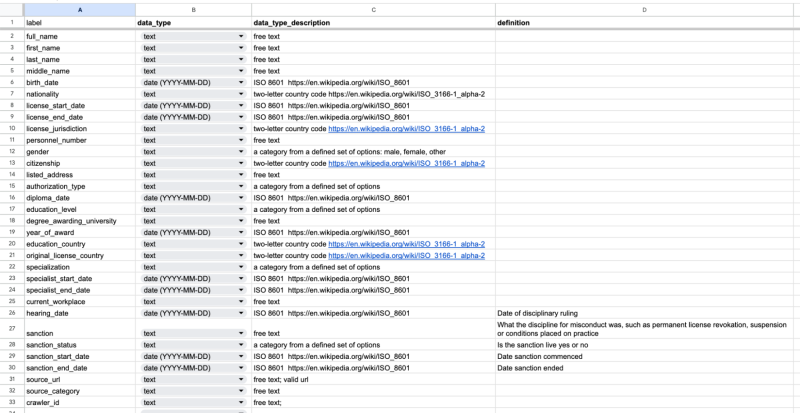

So before doing anything with the data, we needed to clean it up. We created what’s known as a “data dictionary,” a way of describing different types of data in a standardized way and defining how they would be rendered, and agreed to use it for all our scrapers. For example, our dictionary laid out that in our database, names would always be represented as [First, Last], and birthdates would be rendered in the same way. Names and other titles were transliterated from Cyrillic or Greek into the Latin alphabet, using a tool called Unidecode.

A screenshot of our data dictionary.

Still, this didn’t magically create the perfect dataset; the data was so messy that we sometimes had to make decisions manually.

A particular challenge was figuring out how to handle names that contained more than just a first name and a surname — for example, middle names or patronymics. One doctor who ended up becoming a main character in our story appeared in databases as both IULIU IOSIF MARIAN STAN and IULIU-IOSIF-MARIAN M STAN. Although Excel has a function you can use to automatically split names, it is error prone and we wanted to avoid it. So we ended up using a formula to identify names with more than three words, then asking journalists from those countries to reorder the names manually, using their knowledge of the cultural context. This worked, but it was time-consuming — and ordering names with more than three words was so challenging that it remains one of the main weaknesses of our database.

Asking Our Data Questions

Finally, it was time to dig in and ask our database questions, in an effort to get a deeper understanding of what was going on. But what could we ask?

We started by making a list of every name that appears as revoked or reprimanded in one country, but licensed in another. When we did that, we got about 2,000 names to dig into. We found some false leads in there, but also some that were very clearly interesting.

To narrow down the results, we asked several more precise questions to our database: Are they people with the same name and the same date of birth who appear as reprimanded in one country, and licensed in another? With the same speciality? With the same date of graduation?

Questions like these could also be used to work around the different “weak spots” of our database. For Italy, where we could not scrape license data from the registry, we asked our database to give us the name of every Italian-educated doctor whose license had been revoked in the U.K. and Norway. Then, we manually checked the Italian registry to see if these people were still licensed there. We ended up finding eight cases, which became the basis for stories published by our Italian partner, L’Espresso.

Once we established a list of leads, reporters still had a lot of work to do — research, document-gathering, and old-fashioned shoe-leather reporting. Journalists first needed to find proof that the person was indeed the same person in both countries by matching other identifiers, such as dates of birth and other biographical elements.

More importantly, reporters needed to find the reason behind the revocation for each doctor’s license. We wanted to make sure we were writing about people who had committed substantial offenses, and hadn’t just had their licenses taken away on a technicality.

Some countries make this reasoning easily available. The U.K. publishes its medical tribunal's decision on the website of the General Medical Council (GMC). In Sweden, Norway, and Finland, reporters were able to file freedom-of-information requests to get documents regarding disciplinary actions.

In other countries, the process was not so straightforward. In the Netherlands, also one of the most transparent countries, lists of doctors and medical license revocations were available, but not the reasons for revocations. Our partners there found a clever solution, cross-referencing the revocations list with anonymized court records to find matches by date.

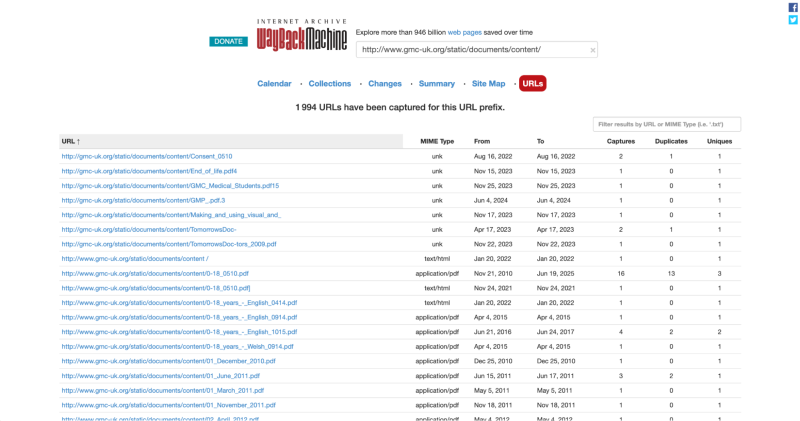

In the U.K., decisions older than 10 years are deleted from the GMC’s website. Reporters tried to obtain such decisions through freedom-of-information requests, but these were rejected. We found a workaround using the Wayback Machine, a tool used to archive previous versions of websites, where we could find all documents previously uploaded by the GMC.

OCCRP

Finally, reporters needed to confirm that the doctor was indeed licensed in a new jurisdiction, and practicing medicine. While this proved relatively easy in most countries, it was a challenge in others. In Germany, where license data was not freely accessible, reporters confirmed that doctors were indeed licensed by asking local medical associations, or checking their insurance status on the website of the Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians. In other cases, we made appointments or visited the doctors’ offices to make sure they were currently practicing.

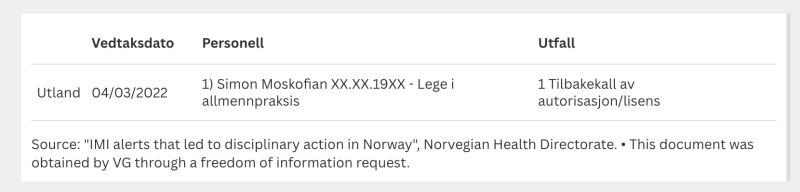

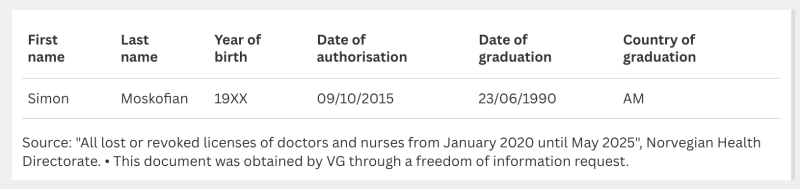

Let’s look at how this worked in practice, using the same example of Simon Moskofian.

He came onto our radar after we queried our database for a full_name that appears in at least two different countries, both in a “revoked” dataset and in a “licensed” dataset.

The name SIMON MOSKOFIAN popped up. It's a rare name, appearing only four times in our datasets, so it seemed unlikely to be a false lead.

To confirm that this was a case we actually wanted to report on, we needed to prove several additional things:

That the Simon Moskofian whose license was revoked in Sweden and Norway is the same Simon Moskofian currently practicing medicine in Cyprus. Luckily, we found his personal Facebook page, on which he himself confirms that he worked in Sweden for eight years. There is only one person in the Swedish health registry with this name. Other details also match: his Cyprus license shows that he graduated from medical school in Armenia in 1990, which matches with the data we have from Simon Moskofian's license in Norway.

That Moskofian’s license was indeed revoked in Sweden and Norway for substantial reasons. Reporters filed a freedom-for-information request to get documents from the health authorities to confirm this.

That he was indeed licensed in Cyprus. Licensing data in Cyprus is freely available online in the registry, so this was not hard to check.

That he was actively practicing medicine in Cyprus. To prove this, reporters contacted Simon Moskofian directly at his clinic.

Once all these points were confirmed, we added Moskofian to our count, and he became a part of our larger story. (When we reached out to him for comment, he said he had been overworked and burned out during the seven years that he worked in Sweden, but that the fact he had been allowed to work there for so long showed he was not incompetent.)

In the end, our database led us to 103 clear cases in which doctors were banned in one country, then licensed to practice elsewhere. The data also pointed to many other cases that we're still exploring, even though we haven't yet been able to fully confirm them through public documents. And this is just the beginning — we’re already expanding the “Bad Practice” project to the Americas and beyond, and we'll keep refining our data collection practices so the journalists we work with can fully explore this issue.

.jpg/2b702c3845c8b7a84b3cf92692a7695e/borderless-doctors-data-(4).jpg)