Reported by

The large-scale production of the synthetic drug Captagon has been sharply disrupted since the fall of Syria’s Assad regime a year ago, with authorities dismantling dozens of drug laboratories and storage sites, according to a United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime research brief.

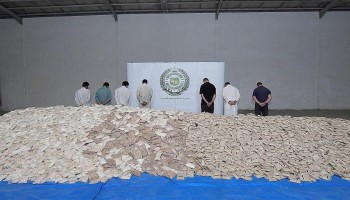

The production of the synthetic drug Captagon has “drastically changed,” according to the ongoing research that is expected to be completed in June 2026. Around 80 percent of the drug seized in the Middle East between January 2019 and November 2025 originated from Syria but following the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in December 2024, Syria’s transitional government has dismantled 15 industrial-scale laboratories and 13 smaller storage facilities, the paper said.

Captagon, a powerful amphetamine, has fueled a booming illicit industry in Syria over e past decade. With the war crippling the formal economy, the country became the world’s largest narco-state under the Assad regime.

Prior to December 2024, Captagon production facilities in Syria operated with the capacity to manufacture “millions of tablets,” according to the UNODC. The agency warned that stockpiles produced during the Assad era could still “sustain supply for a couple of years, feeding ongoing trafficking across the region if not intercepted.”

In June, Syria’s new interior minister announced on state television that his government had orchestrated a complete crackdown on the drug. “We can say that there no longer is any factory that produces Captagon in Syria,” said the minister, Anas Khatab.

While production may have been halted in Syria, Captagon has continued to flow, albeit with “shortages in several destination markets, which may be the result of increased interdiction over the past year,” according to official data verified by the UNODC. Since December 2024, authorities across the Arab region have seized at least 177 million Captagon tablets—equivalent to roughly 30 tonnes.

To adapt to the intensified crackdown on Captagon trafficking, the agency noted that “traffickers continue to explore new routes and are increasingly using diversion and repackaging points,” including in Western and Central Europe and North Africa.

“While the drug market expanded in recent years and divided the region, the need for action is now bringing it together,” said Bo Mathiasen, UNODC Director for Operations, in a press release. He added that “countries are collaborating, sharing intelligence, and conducting joint operations, leading to record seizures in 2025.”

Despite this apparent progress, the UNODC cautioned that “focusing exclusively on the supply side of the drug problem carries significant risks.” The agency stressed that without addressing underlying demand, drug trafficking and consumption are likely to shift toward other substances.

“Trafficking and use may move toward drugs such as methamphetamine, with new routes and actors emerging to fill the gap,” the UNODC warned.

Such a shift is already visible in Jordan. While Captagon use has declined, users [are[ shifting toward other substances such as crystal meth, synthetic cannabinoids (“Joker”), or misused prescription drugs. These alternatives are increasingly seen in some communities, especially due to ease of access or local production,” Dr Mousa Daoud Al-Tareefi, president of The Jordan Anti-Drug Society, told OCCRP.