Two years after two board members quit the Georgian Basketball Federation in protest of a player development deal with Spain’s Saski Baskonia team, Georgian prosecutors are investigating the program.

Giorgi Kondakhashvili, a lawyer for a Georgian family that sent their son to Baskonia, says the investigation is looking into possible misappropriation and embezzlement of government funds. Prosecutors have taken documents from the Georgian Basketball Federation office, Kondakhashvili said.

The prosecutor’s office declined to comment.

The contract calls for the state-funded Georgian Basketball Federation to send its most promising teenage basketball players to Saski Baskonia, a top professional club in Spain, where coaches would help develop them.

In a few years, the idea was that the best of the Georgian players would go on to sign big-money contracts with the National Basketball Association (NBA) in the United States or with top European teams. The Georgian Basketball Federation would then collect big “contract transfer” fees, presumably amounting to more than it paid the Spanish club for its training services, and make a profit.

The federation signed the five-year contract with Saski Baskonia on Sept. 24, 2014. Nearly four years later, Georgia is on track to spend €2.5 million over the span of the contract and has almost nothing to show for it.

The deal is a startling departure from the usual system for finding and developing young athletes, and Georgian prosecutors have begun asking questions about how and why it was signed. They have been interviewing current and former federation officials since April.

Potential convictions could carry prison time of seven to 11 years if the amount of money involved is more than about US$ 4,000, Kondakhashvili said.

Hoop Dreams

A big-time professional basketball contract is a dream for young athletes in many countries. According to Forbes magazine, the average NBA salary of $6.2 million is the highest in U.S. professional sports.

The sole Georgian in the NBA today is Zaza Pachulia, who was drafted in 2003 and played the last two seasons for the NBA champion Golden State Warriors in California. He is reportedly signing a contract with the NBA Detroit Pistons for the 2018-2019 season. Another Georgian, Tornike Shengelia, signed with the Brooklyn Nets in 2012 and spent two years in the league.

The odds of any athlete making it to the NBA are small. Only 60 players are drafted annually out of thousands eligible around the world. Outside the U.S., dozens of leagues and hundreds of professional clubs pay less than the NBA.

Most young athletes who make it professionally begin playing in school, sometimes gaining extra practice in skill camps where they are drilled and coached.

Professional teams and other basketball organizations often sponsor such training and invite sports agents and scouts to assess the talent.

If a player is chosen for an extended professional tryout, the team usually covers expenses such as air fare, stipends, housing and schooling costs.

That’s not how the Georgian deal with Baskonia is structured.

The five-year contract instead calls for the Georgian Basketball Federation to pay Baskonia €2.1 million up front, or €500,000 annually, with the hope — but no guarantee — that Georgia would earn part of it back through contract transfer fees if any of the players Baskonia accepts go on to sign professional deals.

Key points in the contract include:

Between 2015 and 2019, the federation pays Baskonia €300,000 a year for a total of €1.5 million. In return, the Spanish club is meant to invite and coach young Georgian players.

The federation must spend €200,000 a year (for a total of €1 million) to run a training program in Georgia. Some of the money covers flying in specialists from Spain to develop a basketball campus for young players selected by the Georgian Basketball Federation.

If any of the participating Georgian players sign pro contracts through 2024, Georgia and Baskonia will split any transfer fees 50-50.

Baskonia compiled a list of non-Georgians playing for the club. If any of these players sign pro contracts before 2024, Georgia would receive 30 percent of any transfer fee. (Four players on this list told reporters that this was news to them.)

According to an addendum to the contract, if Georgia hasn't recouped €1.5 million from the transfer fees by 2024, Baskonia says it will refund the difference.

Baskonia says its unusual setup with Georgia is just an attempt to help the country develop its basketball program by providing promising players with training they wouldn’t otherwise receive.

“They are not world-class players that we would normally invite to Baskonia,”

said Jesus Vasquez, the club’s international manager.

A Hitch with the NBA

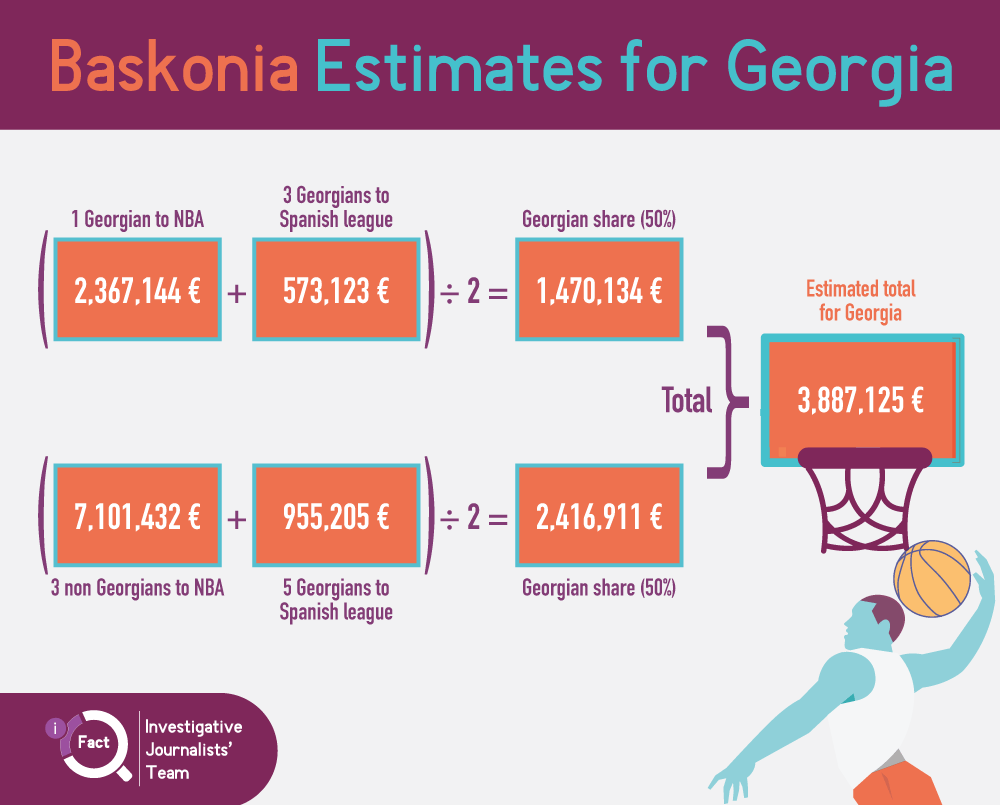

The main problem, according to an independent expert, is that the contract is based on unrealistic numbers. Baskonia estimated that a Georgian player who made it to the NBA would fetch a transfer fee of €2.37 million, entitling Georgia to close to €1.2 million.

But for 2018, NBA contract rules cap such transfer fees at $700,000. Anything more than that has to come out of the player's own pocket.

Shengelia is the only Georgian player to jump from Europe to the NBA in recent years. He left a Belgium team in 2012 and signed with the Nets for just $473,604. The transfer fee was only $300,000, a fraction of the amount Baskonia estimated Georgia might make under its current arrangement.

So far, eight young Georgians have gone to Spain under the contract (though two quickly returned home). None are close to signing big-money deals.

The Genesis of the Deal

The Georgian players who have gone to Baskonia. (Graphic: iFact.ge) Saski Baskonia is a 58-year-old club that plays in both the Spanish league and EuroLeague. It was a powerhouse from 1995-2010, winning Spain’s King’s Cup (“Copa del Rey”) six times and reaching the final four in the EuroLeague five times.

The Georgian players who have gone to Baskonia. (Graphic: iFact.ge) Saski Baskonia is a 58-year-old club that plays in both the Spanish league and EuroLeague. It was a powerhouse from 1995-2010, winning Spain’s King’s Cup (“Copa del Rey”) six times and reaching the final four in the EuroLeague five times.

Recent success has been more elusive, though Baskonia did reach the EuroLeague Final Four in 2016, and this year finished second behind Real Madrid in the Spanish league.

Shengelia, who left the NBA in 2014 and signed a three-year contract with Baskonia, is the club’s best player and its captain. Now 26, he averaged 14.9 points per game this season in Spanish League competition. He is now debating whether to try to return to the NBA.

His father, Kakha Shengelia, says he played an unwitting role in the federation’s unusual deal with Baskonia. Kakha was vice president of the Georgian Basketball Federation and a board member in 2014 when Tornike Shengelia returned to Europe.

That year, Kakha went to see his son play, along with then-Federation President Mikheil Gabrichidze and current Federation Secretary-General Giorgi Kartvelishvili.

Former Minister of Sport Levan Kipiani was also there, according to Vasquez, the international manager for Baskonia.

“It was not a business trip,” Vasquez says. “They just came to see Tornike play. But they were talking about the federation's problems developing players. We agreed that good young players needed to get out of Georgia to develop. We knew the federation couldn't afford to send players here. So we came up with the formula so it would be an investment for Georgia instead of an expense.”

Baskonia estimated that one Georgian and three non-Georgians could reach the NBA over five years, while three Georgians and five non-Georgians could play in the top Spanish division. That would have put the federation’s share of the transfer fees at €3,887,125, a healthy profit on the €2.5 million it was obligated to spend under the contract.

Saski Baskonia’s estimates for how much money the Georgian Basketball Federation could earn from the deal. (Graphic: iFact.ge)

Saski Baskonia’s estimates for how much money the Georgian Basketball Federation could earn from the deal. (Graphic: iFact.ge)

According to Kakha Shengelia, the federation board never really discussed the Baskonia contract. Instead, it used the inflated figures to convince the Georgian government to approve the €2.5 million expenditure.

The sum of €2.5 million over five years is a huge expense for a small country like Georgia. The federation's annual budget is only about €3 million and the budget for the entire Ministry of Sports exceeded €50 million for the first time in 2017.

The yearly budgets of Georgia’s Basketball Federation show that the €2.5 million deal represents a large percentage of its yearly budgets. (Graphic: iFact.ge) “I'm very ashamed to say this, but they used me,” Kakha Shengelia says today. “The federation kept telling everybody: ‘Tornike's father is with us on this.’”

The yearly budgets of Georgia’s Basketball Federation show that the €2.5 million deal represents a large percentage of its yearly budgets. (Graphic: iFact.ge) “I'm very ashamed to say this, but they used me,” Kakha Shengelia says today. “The federation kept telling everybody: ‘Tornike's father is with us on this.’”

Neither Gabrichidze nor Kipiani replied to reporters’ questions.

Kakha Shengelia resigned from the basketball federation in 2016. He made these points about the deal with Baskonia in letters to the Ministry of Sports and the Georgian Olympic Committee:

No information was sought from any other foreign team and the international market was not examined.

There was no formal vote by federation board members.

The federation had already transferred more than €735,000 to Baskonia and had nothing to show for it.

A Rocky Record

There were problems from the beginning. The first two Georgian players who made the trip to Spain under the deal with Baskonia were back home in less than four months.

Although basketball practice begins in the summer, 16-year-old Giorgi Turdzeladze didn’t get to Spain until October 2015. Instead of practicing with Baskonia, he was sent to play with a fourth division team in Leon and returned to Georgia in January 2016.

“Turdzeladze was a good player, but Baskonia needed to focus on coaching younger players,” said Vasquez. Asked why Turdzeladze was selected if he was too old, Vasquez said it was hard to find players in “one little country with four million population.”

Nika Darbaidze was 17 when he went to Spain in February of 2016. He ended up playing with a fourth division team in Mieres and came home when the season ended that May. Darbaidze says the Mieres coach told him he could return, but he decided to stay in Georgia when he was invited to play on the Georgian national team.

Both Georgian players blame their late season starts on visa issues at the Spanish consulate in Turkey.

“I needed to be in Spain in August to get in good physical shape, but because of document problems, I didn’t get there until October,” Turdzeladze said. He said he received no coaching from the Baskonia organization while he was playing in Leon.

Darbaidze said that by the time he arrived in Spain, there was no room for him on any of Baskonia’s team rosters.

Luka Bulashvili went to Baskonia only because his family paid. He’s still playing in Spain. (Photo: iFact.ge) One other Georgian went to Baskonia in 2015, but he wasn't selected in a camp. Luka Bulashvili went because his father paid Baskonia €17,000 himself and spent another €8,000 for his son's first-year expenses.

Luka Bulashvili went to Baskonia only because his family paid. He’s still playing in Spain. (Photo: iFact.ge) One other Georgian went to Baskonia in 2015, but he wasn't selected in a camp. Luka Bulashvili went because his father paid Baskonia €17,000 himself and spent another €8,000 for his son's first-year expenses.

At one point, Bulashvili was listed as one of the players whose training counted under Baskonia’s contract with the Georgian Basketball Federation. His father Levan complained to Georgian sports officials and asked whether the €30,000 budgeted for each player’s expenses had been sent to Baskonia even though the Bulashvili family paid Luka's way.

Levan Bulashvili says he still hasn’t received any answers, but Luka’s name has been removed from the contract list.

Luka Bulashvili was invited to play this year for Gran Canaria II in Spain's fourth division. He returned to Tbilisi in April to play for the under-20 national team and scored 32 points in two games as Georgia defeated teams from Belarus and Latvia to win a European Youth League championship.

Normal Roads to the NBA

Compare this with Tornike Shengelia’s route to the NBA.

According to his father, Tornike was just short of 15 years old in 2005 when Georgian sports agent Levan Mikeladze organized a camp for 60 young players in Batumi and invited a scout from Valencia. Shengelia’s performance earned him a four-day tryout in Spain, after which the club signed him. Valencia wasn’t paid and covered Shengelia’s travel, visa expenses, and schooling.

By the end of his second year, Shengelia was on Valencia’s first-division team at a monthly salary of €5,000. In 2010, he moved to a team in Belgium that offered more playing time; and in 2012, at age 21, he was a second-round NBA draft pick. The Brooklyn Nets paid a $300,000 transfer fee.

Georgia’s best young player today, 19-year-old Goga Bitadze, attended one day of Baskonia’s camp in Georgia when he was 15 and never returned. He moved to Serbia the next year.

Bitadze, who stands 6 foot, 11 inches tall, decided on June 11 to wait one more year before trying for the NBA draft. He was a key performer this year for Mega Bemax in the Serbian league, averaging over 12 points a game. NBA scouts said he could have been selected in the second round.

Non-Georgian Players Unaware of Fee Clause

Tornike Shengelia's road to the NBA began when Valencia saw him at a camp in Batumi. (Photo: iFact.ge) It doesn't appear Georgia will collect any transfer fees in the near future under the portion of its contract that covers non-Georgian Baskonia players.

Tornike Shengelia's road to the NBA began when Valencia saw him at a camp in Batumi. (Photo: iFact.ge) It doesn't appear Georgia will collect any transfer fees in the near future under the portion of its contract that covers non-Georgian Baskonia players.

The best of these players whose deals would have resulted in a payment to Georgia is Serbian native Filip Petrusev. He went to Baskonia in 2014 at age 14, but left in 2016 to play U.S. high school basketball. He’s set to play for Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington, beginning in October.

Petrusev was one of four players reached by reporters who said he had no idea that Georgia could collect money from a transfer fee if he ever signs a pro contract. Contacted via Facebook, he said he and his brother David, who is also on the list, knew nothing about it.

In a telephone interview, their father Dejan Petrusev also said he was unaware of the arrangement.

“Why should they know?” Baskonia's Vasquez asked when told the players were unaware their futures were intertwined with the federation-Baskonia deal. “They signed a 10-year contract with us. They are happy to be with us because this is their path to get into pro basketball.”

Dim Prospects

Baskonia says it spends €30,000 per year for accommodations and personal expenses for each Georgian player who comes to Spain. It lists annual costs for youth scouting there at €96,000, athletic facilities €25,000 and medical expenses of €40,000.

Player development requires patience, Vasquez said, explaining that a 15-year-old Georgian selected for the Baskonia program may stay in it for 10 years and sign with a professional team at age 25.

But the reality is NBA teams are seldom interested in signing new 25-year-old players. Americans often spend as little as one year at a university before trying to sign with the NBA around the age of 19.

So far, Georgia has spent less than €200,000 of the €1 million it committed to player development under the Baskonia contract. The fourth training camp for the program was held in April on two courts in Tbilisi.

Over five days, more than 150 boys ages 12-17 ran drills and played half-court games under the watchful eyes of Georgian and visiting Baskonia coaches. (The federation’s deal with Baskonia calls for some Georgian coaches to get additional training on site in Spain, but the Georgians say so far only one has been invited for a two week stint.)

The players in Tbilisi were young, enthusiastic — and small. None seem likely to ever be big or strong enough to play professional basketball.

If Georgia receives less than €1.5 million by 2024, Baskonia is supposed to refund the difference.