Regina Martínez was a reluctant expert on Mexico’s most violent drug gangs.

The veteran journalist didn’t set out to cover crime and corruption — but the stories kept finding her, piling up as fast as the bodies in her home of Veracruz.

The once placid state, hugging the Gulf of Mexico and best known for its deep-water port, had been convulsed by waves of cartel violence that many, including Martínez, felt was being abetted by its government.

Martínez watched it all unfold, and traced the deterioration in her work. The fourth week of April 2012 was a typical one. In just five days, she filed nine stories on all kinds of crime and corruption to her editors at the Mexico City-based Proceso magazine: “Commander Chaparro,” the alleged financial mastermind of the Zetas drug gang, taken into custody. Nine police officers arrested for collusion with cartels. An opposition politician suddenly dead at home, his friends certain he had been murdered.

That story would be her last. She was killed in her bathroom the night after it was published, beaten and strangled with a washrag.

Her murder at age 48 was as brutal as the crimes she had spent years writing about. It was also emblematic of a spate of violence against journalists that has haunted Mexico over the past two decades. Many of these killings, which were accompanied by a flood of gang activity across the country, remain unsolved or only haphazardly investigated.

“Sometimes we have the impression that as journalists, in such a violent context, that we have to pay a certain share of blood to contribute to the democratization of public life, of our state, of our country.”

Journalist Elfego Riveros

In Martínez’s case, local prosecutors in Veracruz concluded she was killed by a drug-addicted male prostitute they claimed was her lover. The prosecution built a case that her lifestyle as a single female journalist meant she was likely to bring men into her home for sex.

This conclusion was accepted by a court, which threw the man in jail and ordered the case closed. But eight years after the murder, a group of media outlets, including OCCRP, are taking another look. On close examination, the official version looks strikingly improbable.

There are other issues, too. Months before she was murdered, Martínez expressed serious concerns about her safety. Her home was broken into and robbed. A special prosecutor who investigated the case told OCCRP that she witnessed serious errors in the handling of evidence at the murder scene. She does not buy the official version of events, she said. And the only person convicted of the murder says he was tortured into confessing.

Martínez had been working in an increasingly hostile environment. She had reportedly been blacklisted by the Veracruz government, headed by Fidel Herrera Beltrán. The seasoned politician was seen as deeply enmeshed with Los Zetas, the vicious drug gang that had spawned much of the violence in the state.

That treatment continued under Herrera’s successor and political ally, Javier Duarte, who resented the press corps for their blow-by-blow coverage of his struggles to get drug violence under control. (Duarte would be jailed in 2018 after pleading guilty to charges of money laundering and criminal association. He responded to questions from Forbidden Stories with a series of tweets from prison, where he is currently serving a nine-year sentence. “I have never censored anyone’s freedom of expression or freedom of the press,” he wrote. He denied any involvement in Martínez’s killing.)

Many of Martínez’s colleagues are certain that — as with many other reporters across the country — she was silenced because of her work.

Mexico is one of the deadliest countries in the world for journalists, with 119 killed since 2000, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Veracruz is the deadliest state in Mexico. Twenty-eight reporters have been murdered there in the past two decades.

So many have fled Veracruz and other gang-riddled areas of the country that there is now a club for displaced journalists based in Mexico City. Several of its 150-odd members knew Martínez.

"Everyone was running away,” said one of her friends, Andres Timoteo, who left Veracruz as soon as he heard of her murder. “We didn't know who would be next.”

Timeline: A Dangerous Career

"Her Whole Life Was Work"

Born in a small town just outside Xalapa, the capital of Veracruz, Martínez was one of 11 children. She studied journalism in college and spent close to two decades reporting for local outlets before taking a job as a correspondent for Proceso in 2000.

She was a tiny woman, just 1.48 meters tall, and imbued with a natural reserve. Her friends and colleagues recall her as exceedingly cautious, quiet, and disinclined to discuss her work as a reporter — which, in the months leading up to her murder, was becoming increasingly dangerous.

Partly that was because of the stories she covered — many focused on gang violence and links between organized crime and politics — and partly because of her own drive to dig deep.

Martínez wasn’t what’s known in Spanish as a “periodista de escritorio,” a journalist content to sit at her desk all day and make calls. She needed to be out in the field, especially in the rural and indigenous communities most affected by organized crime.

“She wasn’t an office, a typewriter, an internet, a phone person,” recalled Elfego Riveros, who ran a local radio station for years and considered Regina a colleague. “She was someone who went out to interview, to take pictures, and to publish the stories other media wouldn’t.”

“Her whole life was work,” added Norma Trujillo, a former colleague who has been campaigning to raise awareness of her case.

And because Martínez wrote for a publication with national reach, that work could have a major impact.

"I think that one of the problems Regina had was that due to the environment in which she worked, the information transcended [Veracruz],” Trujillo explained. “She was more widely read. It was coming out from the state borders, which was what the government did not want at that time.”

"What the local media did not want to publish was published through Regina Martínez," said Jorge Carrasco, Proceso's current editorial director.

In the months before her death, Martínez filed a flurry of investigative pieces on topics including migration, abuses against indigenous communities, and relationships between drug cartels and politicians.

She was also digging into what might be Mexico’s most sensitive issue: disappearances.

Thousands of Mexicans have gone missing amid the bloody drug wars of the past two decades. Some have been discovered piled in mass graves months or years after disappearing. Some are never found. For their families and friends, their loss is like an open wound, never resolved or understood.

By official count, there are 5,070 desaparecidos in Veracruz, a figure that skyrocketed after Duarte took office. Unofficially, it is widely believed there are many more.

A public official with extensive experience in several Veracruz state administrations, who spoke to Forbidden Stories on condition of anonymity, said disappearances were especially sensitive in Veracruz.

“It’s something that stays alive,” he said. “It’s not like a homicide, where a person dies and it’s over. The desaparecido has disappeared, you don’t know if he is dead or alive. Because of this, the family members are always putting pressure on the government. And the government doesn’t like being pressured, or above all, being made to look bad.”

It was a major investigation into this topic with which Martínez made perhaps the biggest stir of her career in late September 2011, when she and a colleague wrote a cover story for Proceso that sparked a national outcry.

“Veracruz, Zone of Terror” was a scathing indictment of the gang violence that had taken over her home state. It told the story of how the Zetas drug cartel had infiltrated the state government during the administration of Herrera and reached a peak toward the end part of his term.

When he was replaced by Duarte, the story said, the region’s gangs embarked on a period of realignment, leading to a crescendo of murder and kidnapping that the new governor could not get under control.

The story was accompanied by a grisly cover image showing the 35 bloody corpses that had been dumped on a main street near the port of Veracruz, just blocks from where prosecutors had been holding a meeting on security issues. The government’s claims that all the dead were Zetas, gunned down by the Gulf Cartel, turned out to be false.

Her story, published in a national outlet, infuriated Duarte, who had been trying to rehabilitate his gang-riddled state’s reputation.

Ironically, almost nobody in Veracruz itself was able to read the article in print. That week’s issue of Proceso was itself made to “disappear” — bought off newsstands by mysterious strangers as soon as it arrived.

“She was a pesky journalist,” said the ex-official who spoke with Forbidden Stories. “I think the mass graves were the straw that broke the camel’s back. … No government likes it when the cloth is pulled from people’s eyes.”

Doors Closing

As she continued to cover organized crime and developed a reputation as a fierce, incorruptible reporter, Martínez’s professional life got harder.

She was barred from press conferences and kept in the dark about official events. Press releases stopped reaching her.

It later emerged that the state government had drawn up a blacklist of journalists in Veracruz who would be barred from daily governmental events. Martínez’s name was on it.

"There was very noticeable harassment against her,” said Ana Laura Pérez Mendoza, president of the Veracruz State Commission for the Attention and Protection of Journalists. The entire state cabinet closed its doors to Martínez, she said: "Duarte was very intolerant.”

Jorge Carrasco, Proceso’s current editorial director, last saw her in November 2011, when he was still working as a reporter for the magazine.

Regina abandoned her usual reserve and talked to him for hours. She said the situation in Veracruz was becoming more dangerous, and she no longer wanted to report on crime.

The problem was that the murders and executions in Veracruz never seemed to stop. Somebody had to cover them for the national media. And that somebody was usually Martínez.

A month later, in December 2011, something disturbing happened.

The journalist came home one day to find her bathroom steamed up, as if someone had been taking a hot shower there just seconds before. Her soaps had been used. The equivalent of around US$5,000 was missing from her house.

The incident terrified her, but she was equally terrified to go to the police.

"I know she was afraid. But even though we told her to officially report it, she didn't want to do it because she didn't believe in [the possibility of] justice," said Trujillo.

But she did keep reporting.

A few months later, in April 2012, Proceso published an article blaming two high-ranking Veracruz officials for complicity in the state’s takeover by organized crime: state attorney Reynaldo Escobar Pérez and head of public security José Alejandro Montano Guzmán.

The article directly linked Escobar to organized crime and the growth of cartels during Herrera’s government. It claimed Montano, a man who often spoke of his humble origins, had amassed properties worth some US$7.3 million.

It was written by Jenaro Villamil, a journalist based in Mexico City, who traveled to Veracruz for reporting. There, he met with Martínez to gather insight on the situation, and they were seen in public together.

The issue of Proceso where his story appeared was also made to disappear from newsstands.

The Murder

Because her career was so dangerous, Martínez led a tightly regimented domestic life. She kept her doors locked tight and rarely invited anyone inside her small three-room house in central Xalapa.

Every Saturday afternoon, she bought a week’s supply of handmade tortillas from the same street vendor, who brought them to her door, and a week’s worth of her favorite yogurt drink, Yakult, from another vendor.

She would announce her arrival at Martínez’s house with loud cries: “Yakult! Yakult!” Usually that was Martínez’s cue to emerge, but on the afternoon of April 28, the Yakult lady got no response. That was so unusual that she alerted a neighbor, who started trying to reach Martínez and noticed that her front door wasn’t fully closed. She called the police.

Two officers who responded found Martínez’s battered body on the bathroom floor. She had evidently been there since the early hours of the morning.

The scene was gruesome. The journalist, who weighed barely 54 kilograms, had been surprised on the toilet, hurled into a wall, badly beaten with brass knuckles, and strangled with a cleaning rag. When she tried to fight back, she was bitten and her head was forced into the toilet.

The coroners noted bruises on her face, her right eye, jaw, clavicle, chest, back, and arms. She had broken ribs, a fractured trachea, and two missing teeth.

From the beginning, investigators from the Veracruz Prosecutor's Office homed in on a confusing and, Martínez’s friends say, improbable version of events, claiming she had been killed by two male sex workers, one of whom had been her lover.

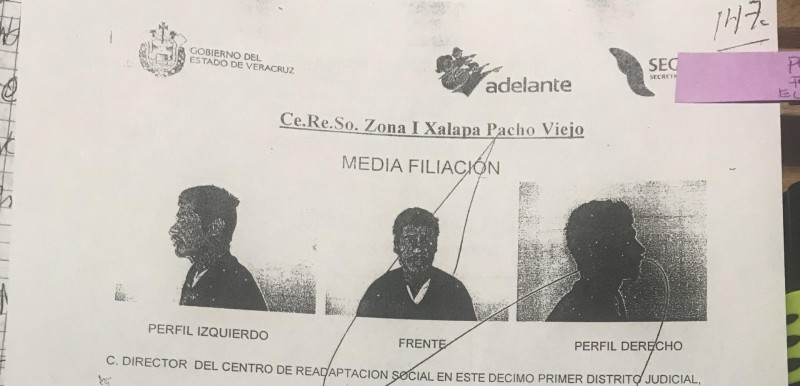

Jorge Antonio Hernández Silva, known as El Silva, was a drug addict with a troubled background. Illiterate, HIV-positive, and often homeless, he had a string of petty thefts to his record. He’d been released from a stint in Pacho Viejo prison for robbery less than a year before Martínez’s murder.

While behind bars, he had gotten to know another inmate who was doing time for robbery. That man, also a drug user and occasional sex worker, went by El Jarocho, a common nickname for a native of Veracruz.

Prosecutors developed a theory that Martínez had been in a romantic relationship with El Jarocho. On the night of her death, they claimed, Martínez had invited El Silva and El Jarocho over to her house for drinks, then left them there while she went out to buy beers. When she returned, she danced with El Jarocho, but soon began arguing with him. Prosecutors said he took her into her bedroom and began beating her, then dragged her into the bathroom. El Silva helped deliver the blows.

Prosecutors began mustering up evidence that Martínez had been “at the beginning of a relationship” with El Jarocho. They got her seamstress to testify that she had recently started ordering shorter skirts and wearing perfume. The impression created by prosecutors was that she was a woman newly in love.

Her friends and colleagues call these conclusions absurd.

"The local authorities said that she was killed because she was the girlfriend of a prostitute, a person who prostituted himself near her home,” said Carrasco. “That this alleged murderer was accompanied by another and then she opened the door.

“In short, an untenable thing.”

Nonetheless, in late October 2012, Veracruz attorney general Amadeo Flores called a press conference to announce the official findings: El Jarocho and El Silva had killed Regina.

El Jarocho had conveniently vanished, but Flores said he had a confession in hand from El Silva, admitting he entered Martínez’s home that night with the intention of robbing her.

"In Veracruz there is no space for impunity," Flores concluded triumphantly.

El Silva was put on trial and sentenced to 38 years and two months in prison.

There was a motive, a confession, and a guilty man. For the state of Veracruz, the case of Regina Martínez’s murder was now definitively closed.

Increasing Doubts

OCCRP journalists reviewed hundreds of pages of documents from the investigation and conducted interviews with key players. They reveal serious holes in the official story.

El Silva, the only person sentenced for the crime, has recanted his confession, claiming he was tortured into telling police he killed Martínez.

"I want to say that they hit me on the back and I feel pain," he said in a statement at a 2013 appeal hearing that was provided to Forbidden Stories by his lawyer, Diana Coq Toscanini.

"They had a sort of buzzer for giving electric shocks, and they put it on my chest and gave me shocks. They did that, but I didn't see who, since I was blindfolded. And last night my chest was in pain."

In August 2013, four months after El Silva’s conviction, a Veracruz appeal court ruled that there was sufficient evidence to overturn the sentence and release him.

Edel Álvarez, one of the judges on that panel, told OCCRP he was convinced by the prisoner’s claims of torture.

He also noted contradictions in prosecutors’ claims about El Silva’s movements on the night of the murder, and said their attempts to paint Martínez as promiscuous were problematic.

“There was a gender issue,” he said.

“It was established in the sentence that due to the journalist's lifestyle and her single status, it was highly probable that she would bring men into her home for sexual purposes."

However, in October 2014, El Silva was jailed again after one of Martínez's brothers filed an injunction against the court decision.

This happened after Veracruz prosecutors “convinced” him that he should appeal and helped him with the filing, OCCRP has discovered.

Luis Angel Bravo, the state prosecutor at the time the decision was made, said in an interview that his office wrote and filed the appeal, although Martínez’s brother signed it.

Bravo conceded this was atypical. Normally, he explained, when a sentence is overruled, “the problem is over” for prosecutors.

“I don’t really remember,” he said when asked whether the lawyer representing Martínez’s brother had been hired by the prosecutors’ office.

“What I do remember is the great deal that was done and the great result that was achieved." And he added “Now, as ranchers say: However it was done, we achieved it.”

El Silva is now back in Pacho Viejo prison under close guard, with not even his lawyer allowed regular access to him, she says.

Laura Borbolla, head of a special federal unit set up to prosecute crimes against journalists, traveled to Veracruz to gather her own information about the murder. She told OCCRP she’d been barred from interviewing El Silva privately.

“I mean, they never told me, ‘We don't want you to investigate. We don't want you to make progress. We don't want you to know what happened here,” Borbolla said. “They never told us. But at the end of the day, putting up so many obstacles and putting up so much time is a very exhausting issue.”

"They did not give us access to him while he was detained at the prosecutor’s office, because perhaps we would have realized immediately whether they had beaten him, whether they had tortured him,” she said.

Veracruz prosecutors had concluded that Martínez’s house was in an "obvious mess typical of a robbery.” But Borbolla says this was not true.

"Everything was in order," she said.

She noted that although Martínez’s work laptop, Blackberry, and television were missing, many other valuables were left untouched, including a DVD player and gold jewelry.

“I've always had reasonable doubt as to whether El Silva really killed her.”

She also accused local police of shoddy forensic practices. They invited journalists into the crime scene a few days after the killing, and scattered so much dust while searching for fingerprints that it was impossible to test some items for DNA.

Borbolla's team found male fingerprints that the state police had missed. Neither matched anyone in the country's national fingerprint database — or El Silva. In fact, his fingerprints were not found at the crime scene at all.

“We're not going to know who killed Regina,” she said. “But I do know who didn't kill Regina.”

Bots and Ducklings

Given the obvious inconsistencies, national media in Mexico remained skeptical about the official version of events.

But the story was taken up by some local media outlets, especially ones with ties to the powerful Partido Revolucionario Institucional, the party of both Fidel Herrera and Javier Duarte.

In Mexico, such pro-government media outlets, known as ducklings, proliferate in droves to do the bidding of their high-ranking backers before fading away nearly as quickly as they came.

Long before Flores announced his official findings that fall, local media was running stories based on leaks from the prosecutor’s office promoting the idea that the killing had been a “crime of passion.”

“The PGJ [local prosecutor] clears up the homicide of Proceso correspondent Regina Martínez,” read the headline of one story on a site called ElGolfo.Info that was widely circulated on Twitter.

Aldo Salgado, an analyst hired by Forbidden Stories, looked into social media accounts that were active at the time, and found that nearly 200 Twitter bots, created on the same two days, amplified these “crime of passion” stories by retweeting them at exactly the same time.

Even as the notion that her murder was a “crime of passion” was spreading across social media, Martínez’s colleagues were struggling in their own efforts to determine the truth.

For one thing, they were being treated with suspicion. Carrasco said that when Proceso asked the authorities to consider Martínez’s work as a potential motive for her murder, the police responded by fingerprinting her colleagues.

“They called them to testify, took their fingerprints, even took prints, plates of their teeth. Then the journalists were told: 'Well, Proceso wants the journalistic work investigated.’ But obviously we didn't want them to investigate her friends. We wanted them to do a technical investigation of Regina's journalistic work," Carrasco said.

There also weren’t many journalists left in Veracruz to continue reporting. After the murder, Martínez’s friend Andrés Timoteo left town immediately. Other journalists quickly followed. They knew the killing wasn’t just about her.

“The message that this crime sends is: If they did this to her, what could happen to us?” said Trujillo.

“And so, among most of us, the fear began to get stronger.”

They were right to be afraid. Just a week after Martínez died, three other photojournalists in the state were killed and their bodies dumped in a sewage canal. The bloodbath continued with the murder in June 2012 of Víctor Manuel Báez Chino, a crime reporter whose body was found just one block from the state’s Government Palace.

In total, about 18 journalists fled Veracruz in the aftermath of Martínez’s murder. Even that hasn't stopped the killing. Over 15 more have been killed since 2012, most recently in September, when the headless body of local reporter Julio Valdivia was found near railroad tracks in a mountainous part of the state.

At a recent press conference, Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador promised he would seek to have Martínez’s case reopened. “There is no reason why these murders should not be solved,” he said of the spate of killings.

But the damage to Mexican journalism has been done. Carrasco compared the effect to “a bomb in a newsroom.”

“For the press in general, there is a before and an after Regina's murder," he said.

“We can no longer investigate in the same way…. We're not reporting to our fullest capacities."