Senior executives at the U.S. company Steward Health Care personally signed off on millions of euros of payments to a Swiss company suspected of funneling bribes to Malta’s former Prime Minister Joseph Muscat, leaked emails show.

There is no direct evidence that Steward knew the payments to the Swiss company, Accutor, ended up in the alleged bribes. But invoices showed that they were often listed as payments through other companies, passed off as expenses for the company jets, or as political consultancy payments, raising questions as to why that was necessary.

Muscat and over two dozen others were arraigned last month on corruption charges related to a multi-billion-euro contract Steward took over in 2018 to renovate and manage public hospitals. They have all pleaded not guilty.

Joseph Muscat, former Prime Minister of Malta.

In April, a Maltese criminal report alleged that Steward had used Accutor and related firms to create a “political support fund,” which diverted money from the hospital contract to Muscat and two senior officials.

The inquiry, carried out by Malta’s Court of Magistrates, led to the charges against Muscat and other officials. Steward Malta and Accutor are among the list of entities recommended for prosecution, but have not been formally charged in court.

U.S. Steward was not recommended for charges. Its chief executive officer was, but he has not been charged.

Steward has said it “strenuously objects” to any suggestion it gave financial favors to Maltese officials and said Accutor was hired as a “business management consultant” to help “regularise” its hospital contract.

The leaked emails offer previously unreported insight into the amounts and timing of Steward’s payments to Accutor, which totaled to roughly 7.6 million euros ($8.1 million) between 2018 and 2020.

This figure included monthly 80,000-euro ($85,000) fees, which the internal emails show were intended for a Pakistani businessman named Shaukat Ali and his son Asad Ali, who were employed by Accutor as consultants.

The Maltese criminal inquiry said that the Ali family had benefited from the hospital contract, which was annulled last year over fraud allegations, and that Shaukat Ali had worked closely with Muscat’s right-hand man, Keith Schembri. The inquiry recommended charges for Ali but there is no record that he has yet been charged.

Reached by OCCRP, Ali declined to comment due to ongoing legal proceedings. “I spoke the truth and I shall prove it in the court,” he said.

Asad Ali (right) and his lawyer, Shazoo Ghaznavi (left).

The emails show that many of the payments were personally approved by a senior Steward executive, Armin Ernst. Ernst did not reply to OCCRP’s request for comment.

Transaction records found in the emails show that some of the Steward payments to Accutor were made at the same time that Accutor and another related company were paying Muscat consulting fees. The fees Muscat received are now at the heart of his corruption trial.

Muscat has previously stated that the payments were for legitimate consultancy work unrelated to the hospital contract. He declined to comment for this story, citing a court gag order. “I deny the veracity of the claims you quote, and this will be demonstrated in court in due course during the proceedings,” he said in an email.

Protesters have repeatedly taken to the streets in Malta since the scandal broke out, demanding that Muscat and other allegedly corrupt officials be held to account. Muscat’s supporters have staged their own protests, insisting the charges are politicized.

Steward told OCCRP that it had “entered Malta in good faith and has been consistently transparent and focused on providing maximum value to patients and taxpayers.”

“We categorically deny any accusations of wrongdoing and will vigorously defend ourselves,” it said.

Ali’s Role in the Steward Deal

In 2015, Malta agreed to pay 2.1 billion euros ($2.2 billion) to a newly formed group of companies called Vitals Global Healthcare (VGH) to renovate three of Malta’s four public hospitals.

Three years later, ownership of VGH was transferred to Steward and it was renamed Steward Malta.

The leaked emails show that Ali was key to Steward taking over the contract.

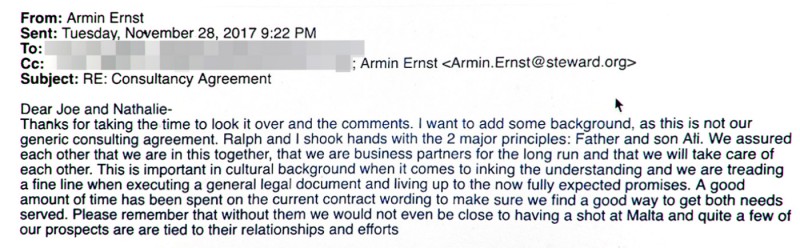

In one message from November 2017, Ernst — the CEO of Steward Health Care’s international branch — wrote that he and Steward CEO Ralph De La Torre “shook hands” with Shaukat Ali and his son Asad, whom he described as the “2 major principles.”

“We assured each other that we are in this together and that we will take care of each other,” wrote Ernst, who had also previously served as VGH’s CEO. “Please remember that without them we would not even be close to having a shot at Malta and quite a few of our prospects are tied to their relationships and effort.”

Ernst said that he and Steward CEO Ralph De La Torre “shook hands” with Shaukat Ali and his son over the Malta deal.

Shaukat Ali obtained a passport in Malta and worked closely with Schembri, Muscat’s former chief of staff, the inquiry said. “Where you find Shaukat Ali you also find Keith Schembri,” it said.

Schembri did not reply to requests for comment.

Shaukat Ali told OCCRP he was involved in talks with Muscat’s administration over the privatization plans that led to the hospital contract. But he has repeatedly denied having any financial stake in the hospital contract.

Emails obtained by reporters show that he might have a bigger role in VGH companies, however. In one 2017 email, Ernst told De La Torre that the Alis held a “silent 60%”. In another message, sent in a 2022 email chain, Ernst described Ali as a “silent VGH shareholder.”

Reached by reporters, Ali said: “I was never owner nor director of VGH or any of its subsidiaries or related companies.”

Asad Ali declined to comment.

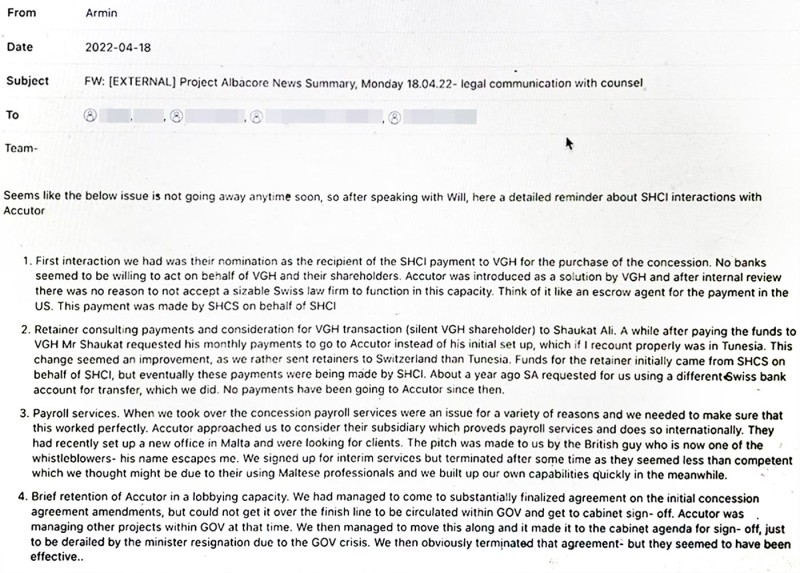

Ernst describes Shaukat Ali as a hidden shareholder and explains the flow of payments to Accutor.

Steward Makes Regular Payments to Ali

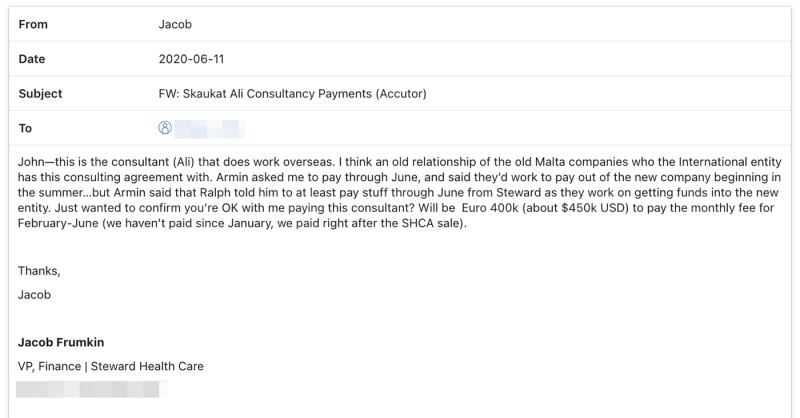

The emails show that Steward was paying Accutor 80,000 euros ($86,000) a month, which according to email exchanges were destined for Ali and his son.

In one January 2020 exchange, for instance, Ernst asked the company to catch up on payments to an unspecified recipient ahead of a meeting in Madrid: “I was sent a note by them that they have not been paid since September. Can we get them caught up?” he wrote.

Asked by the company’s chief financial officer who he was referring to, Ernst wrote, “these are our political consultants. Name is Ali.”

Another employee in the finance department raised concerns, noting that the consulting agreement on file for Ali was “very open ended.” But Ernst dismissed questions about risk and the finance department confirmed that a payment of 240,000 euros ($273,600) was initiated to Accutor to settle up for three months.

About four months later, in May, Ernst asked Steward’s vice president for finance if the company was “current on the Ali consulting payments.”

The vice president asked for clarification: “Sorry, you’ll have to remind me…who is Ali? Do we have an engagement letter or invoice or something we should be paying from?”

“It’s a consulting contract with a monthly retainer payable to Swiss company. I think it is around 80k/ month. Could be listed as Accutor?” Ernst replied.

Finance department employees cited approval from senior Steward executives for payments to Ali.

The contract underpinning the payments was signed in November 2017 with STE Health Co, a Tunisian company which the inquiry said the Alis were behind. (OCCRP could not obtain corporate records for STE.) The contract also offered a 1 million euro ($1.1 million) bonus if Steward obtained the hospital concession within two months and another million for two other milestones.

In a later email chain, Ernst explained that the payments were switched from STE to Accutor upon Ali’s request.

In August 2020, Steward ended its agreement with Accutor, without elaborating on the reasons. Emails and transaction records show Steward then began making payments to another Swiss company, Canberra International, controlled by Ali’s son, Asad Ali, who Maltese authorities charged with bribery over the hospitals deal in June. Asad Ali declined to comment because the proceedings were ongoing.

According to internal financial reports Steward paid Canberra around $450,000 euros ($517,500) between 2021 and 2022 for what was listed as business development.

Payments to Muscat

Muscat stepped down as prime minister in January 2020 under pressure from mass protests over the killing of journalist and anti-corruption activist Daphne Caruana Galizia.

Just over a week after his resignation, on January 22, Muscat signed a contract with Spring X Media AG, which was owned by a Pakistani lawyer named Wasay Bhatti, who also owns Accutor. The company promised to pay Muscat 15,000 euros ($16,000) a month for 36 months. At least two of these payments came from Accutor.

Banks stopped the payments from Spring X Media and Accutor in June 2020 after they found them suspicious, according to testimony in the four-year criminal inquiry that ended this April.

The criminal inquiry alleged that Steward had used Accutor to set up a “political support fund” and “used monies diverted from the concession to fund payments to, or on behalf of” Muscat, Schembri, and a former minister Konrad Mizzi, who also signed a consultancy contract linked to Accutor in 2020.

“The probability of all three politicians forming independent relationships with the same foreign group of companies over the same timeframe without there being a common association, is considered so negligible that we exclude the possibility,” the inquiry said.

Mizzi and Schembri did not respond to requests for comment.

Steward and Accutor have not been charged, though the inquiry recommended charges against Steward’s Malta companies and Accutor. Contacted by reporters, Accutor’s owner, Wasay Bhatti, said: "As you are aware, I may be the subject of proceedings in the near future. In light of this, I prefer not to comment on your queries. Any statements I deem fit will be made by me in court.”

The leaked Steward emails and wire records show that the same month Muscat’s payments were blocked, Steward sent Accutor 400,000 euros ($455,840) from its Bank of America account, which were described in an email chain as an “Ali wire” to cover five months of consultancy payments.

Steward wired 400,000 euros to Accutor via the company’s Bank of America account in June 2020.

Other payments to Accutor varied widely in timing and amounts. Fifteen payments totalling to 5.3 million euros ($5.7 million) — including so-called “milestone payments” made for meeting specific goals — were made in 2018 alone, according to an Excel spreadsheet found in the emails.

A table in another document listed seven payments of 125,000 euros ($142,500) each, made in 2019 and 2020, and an invoice for Accutor consulting services from a related company for the same amount in December 2019.

Those payments appear to overlap with the dates and amounts of eight payments that the Maltese criminal inquiry said went to the “political support fund” for Muscat and other officials.

The inquiry said the payments “were also funded directly from money paid to Steward by [the Government of Malta] for the operations of the Maltese hospitals and overlap with the payments to Joseph Muscat.”

Four other payments Steward made to Accutor in 2019 were listed as “jet expenses” in a ledger submitted to Steward’s auditor EY. They came to $618,000 ($710,700).

In the 2022 email chain, two years after Steward terminated the consultancy contract with Accutor, Steward’s Ernst requested a list of Accutor payments in order to “properly assign them.”

“I have to assume that at some point we will have to account for them in detail,” he wrote in the 2022 email.

A separate email the same day outlined the reasons that Accutor was engaged, which included the company acting in an escrow-like role for the concession payment to VGH, being a recipient for Ali’s monthly retention payments, performing payroll services, and acting “in a lobbying capacity.”

In the message, Ernst referenced a Times of Malta story about payments made to Accutor by VGH. He then forwarded the email to Steward’s counsel general, asking for legal advice.

“It seems like the below issue is not going away anytime soon,” Ernst wrote.