Every day across Turkmenistan, hungry citizens line up for hours to buy small amounts of subsidized food amid an economic meltdown. Ruled by a closed circle of corrupt autocrats, Turkmenistan has spent decades isolated from the world. But its food crisis began in 2016, when Russia abruptly stopped purchasing its natural gas. Suddenly, the Turkmen government was desperately short of dollars to pay its debts.

The Central Asian country was hit by hyperinflation, its currency collapsed, and the government imposed tight restrictions on exchanges.

As a result, imports plummeted, driving food prices out of reach of most families. The government began subsidizing imports by select companies, but supplies are still short.

“They bring very little of everything, and it’s not enough for people,” a public sector employee said on condition of anonymity for fear of retribution.

Little is known about how this food import scheme works, as the government releases no public information about its contractors or the value of the imports.

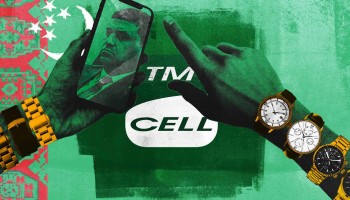

But reporters for Turkmen.News and Gundogar, OCCRP’s Turkmen partners, found that one of the companies that received a food import contract belongs to a 39-year-old nephew of President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, Hajymyrat Rejepov.

Rejepov’s U.K.-registered firm, which has no website and no public history of business activity, received a US$25.7-million contract to import staples like chicken, sugar, and cooking oil as the result of a decree signed by his uncle in November 2016. The document has never before been made public.

The source of Rejepov’s wealth has long been a mystery, though it is widely assumed that he benefits from his familial connection to the president. This deal is the first documentary evidence that he does.

Reporters also discovered where he has spent some of his money.

After receiving the lucrative contract from his uncle, Rejepov acquired a luxurious mansion for his family in Turkmenistan’s capital, Ashgabat. The stately home features marble, Italian crystal chandeliers, and bronze decorations — luxuries far out of reach for ordinary Turkmen.

None of that — not the secret contract, not the nepotism, and not the luxury amidst others’ misery — surprises Rachel Denber, deputy director of the Human Rights Watch’s Europe and Central Asia division.

Corruption “is part of the Turkmen ruling circle’s DNA,” she said. “It’s widespread, it is deeply entrenched, and it is eye-popping.”

Rejepov could not be reached for comment.

Family Affair

In a 2009 diplomatic cable published by WikiLeaks, a U.S. official wrote that President Berdimuhamedov had “gone to great lengths to conceal information about his family and personal life from the public.”

This secrecy is particularly effective within Turkmenistan, where the government controls all media, the internet is censored, and journalists have been arrested and tortured. Still, some details have emerged about the family of the obscure country dentist who became leader of one of the world’s most secretive regimes.

In the early 1980s, when Turkmenistan was part of the Soviet Union, Berdimuhamedov practiced at a rural clinic outside Ashgabat. He worked his way up through the medical system during the waning years of Soviet rule and after his country’s independence in 1991. By 1997, he was health minister under President Saparmurat Niyazov, and in 2001 he was promoted to the post of Deputy Prime Minister, just one step below the president.

When Niyazov died in December 2006, Berdimuhamedov was appointed acting president in a move that arguably violated the Constitution. He was elected to the office two months later, winning almost 90 percent of the vote in an election that featured no true opposition candidate.

Though information about the presidential family’s wealth is hard to come by, social media posts show his nephew Rejepov enjoying the high life. An Instagram photo suggests he spent a holiday in Courchevel, a five-star French ski resort, with a group of friends. Other photos show him travelling in first class on an Emirates flight, driving expensive cars, and showing off lavish watches.

While social media reveals the family’s opulent lifestyle, it has been impossible to discover where they get their money. But Berdimuhamedov’s directive, granting Rejepov the right to import food, provides a possible indication: state contracts.

Millions in Watches

Rejepov’s brother-in-law Ibabekir Bekdurdiyev has his own expensive watch habit.

Foreign Firms

On November 11, 2016, Berdimuhamedov signed decree No. 14995, instructing the Ministry of Trade and Foreign Economic Relations to sign import contracts with seven foreign companies for a total of nearly $60 million. At least three of the companies raise serious questions.

The largest contract, worth $25.7 million, went to Greatcom Trade LLP. The British company’s owners were concealed behind two offshore firms. But it was now responsible for supplying Turkmenistan with 15,100 tons of sugar, 7,000 tons of chicken quarters, 2,083 tons of sunflower oil, 170 tons of butter, and 107 tons of margarine.

Since then, the U.K. has begun to require all local companies to disclose the names of their beneficial owners. Greatcom’s filings show that it was ultimately controlled by Rejepov.

Berdimuhamedov’s decree authorizing Greatcom to import food is a unique document in a country where the president plays a direct role in most facets of governance. It is the only presidential order directly related to food supplies out of thousands of decrees reviewed by journalists.

It likely wasn’t a one-time deal.

“This decree is the president’s signal to Turkmen officials down the chain — from the deputy prime minister in charge of the trade sector to the minister — that, from now on, they should only work with these firms,” said a person in Ashgabat familiar with the food import system, who asked to remain anonymous.

Two other contracts went to questionable U.K.-registered companies.

A company called Staunchest Holdings LP, owned by proxies and with no declared ultimate beneficiary, received a $7.8 million import contract.

Another $3.5 million contract to import over 1,200 tons of sweets went to Intergold LP, a Scottish firm that had been founded less than a year earlier.

Intergold has since been rechristened with the innocuous name of SL024852 LP, and its owners remain anonymous. But the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists reported that Deutsche Bank flagged as suspicious a $1.6-million transfer in 2017 from Turkmenistan’s trade ministry, which was labelled as payment for “confectionary.”

According to Turkmen law, no competitive tender process is required in “exceptional cases” or for goods and services meant for regulated domestic markets. This provides a loophole for the government to sign single-source contracts at its own discretion, as it did in the case of the 2016 food imports.

Rejepov’s Mansion

Though Rejepov’s Instagram account shows off his foreign travel, reporters found additional evidence of his wealth in his home country: He appears to have acquired a home far beyond the wildest dreams of most Turkmen.

The house is in the exclusive Gazha development in central Ashgabat, which was built with almost $547 million of state funds in the runup to the 2017 Asian Indoor and Martial Arts Games. To make way for the development, which includes a brand-new kindergarten, a school, shopping centers, and a park, the government demolished homes and evicted residents without due compensation, according to Amnesty International.

In a 33-minute video posted on YouTube and later removed, an interior designer shows off the results of his work on a three-story detached mansion. The video, which appears to have been shot some time in 2018, offers a tour of riches that includes gilded faucets in the shape of birds, crystal chandeliers, and designer furniture.

“The walls and ceiling here are decorated in Roman style, also of marble,” the designer says about a guest room. “It has one more feature: parquet floors. The owners put down a carpet, but the floor itself is a masterpiece.”

In the living room, he emphasizes the decorative patterns on the doors. “Here we have wood, and these were cast in bronze,” he says, pointing to the ornate designs. “And all such details, even on the furniture, were cast in bronze.”

A clue in the video points to Rejepov’s ownership of the house.

Showing off a spacious bedroom on the third floor, the designer says it belongs to a boy in 8th grade, making him roughly 14 years old. The large bed’s headboard features the initials B.H. in the Latin alphabet.

Journalists were able to identify B.H. as Rejepov’s son Begench, who uses the patronymic surname Hajymyradov, a common practice in Turkmenistan. He even published a photograph from the mansion on his Instagram account.

The house also appeared in a video from Rejepov’s father’s 60th birthday celebration.

A House in Gazha

Profiting from Misery

As Rejepov enjoys his life of luxury, conditions for Turkmenistan’s ordinary citizens show no signs of improving.

As the situation continued to deteriorate last year, the government imposed ration cards in all regions outside the capital and required citizens to purchase subsidized groceries near their legal registration address. Since then, rations have decreased in some areas.

As food supplies fell short of demand, some families began making small profits by showing up early to stand in line and buy groceries before they ran out, only to sell them later at a higher price. Tensions have grown among hungry people worried about how they will feed their families. Arguments, scuffles, and fights have become commonplace, leading the government to post police officers at stores to maintain order and prevent speculation.

In October 2020, residents of Mary, an oasis city in the Karakum Desert, found their rations cut to just two chicken quarters per family each month, and six eggs per person. This April, the city of Balkanabat decreased the monthly ration to one chicken quarter, one liter of vegetable oil, and 250 grams of sugar per family.

Food shortages and long lines are “a source of tremendous stress” said Denber of Human Rights Watch. “It’s obscene that there are people in Berdimuhamedov’s circle or anyone who is possibly making money off of that grief.”

Matthew Kupfer contributed reporting. Aiganysh Aidarbekova contributed research.

Correction, Nov. 12, 2021: This story has been updated to remove a reference to a businessman whose association with Hajymurat Rejepov and government food import contracts was inaccurately described. OCCRP regrets the error.