Speaking before a U.K. parliamentary working group in November 2022, Imran Qureshi, CEO of Bandenia Challenger Bank, boasted of his institution’s innovative use of blockchain technology and streamlined verification processes. The British member of parliament who had introduced Qureshi, Martin Docherty-Hughes, gushed that Bandenia Challenger aimed to “revolutionize the trade finance and mortgage industry in Europe, the Middle East and Africa.”

What Qureshi’s booster didn’t realize was that the bank didn’t really have the noble aim of reinventing finance. In fact, it isn’t a bank at all.

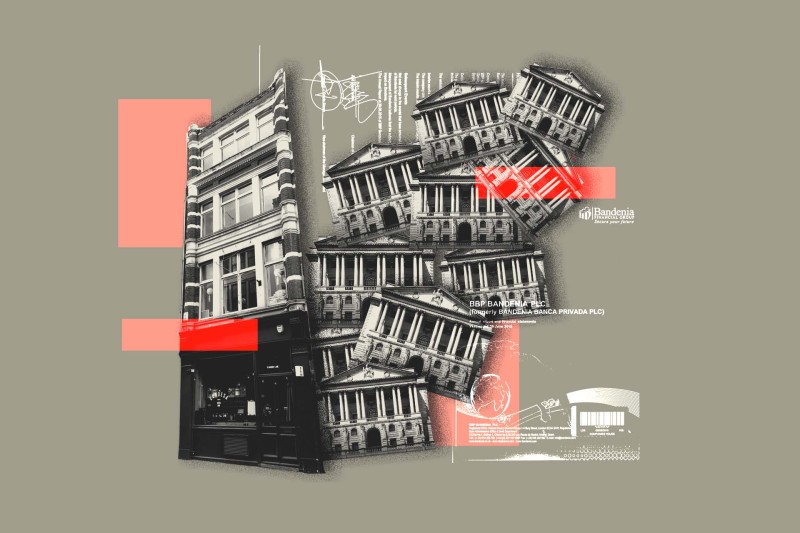

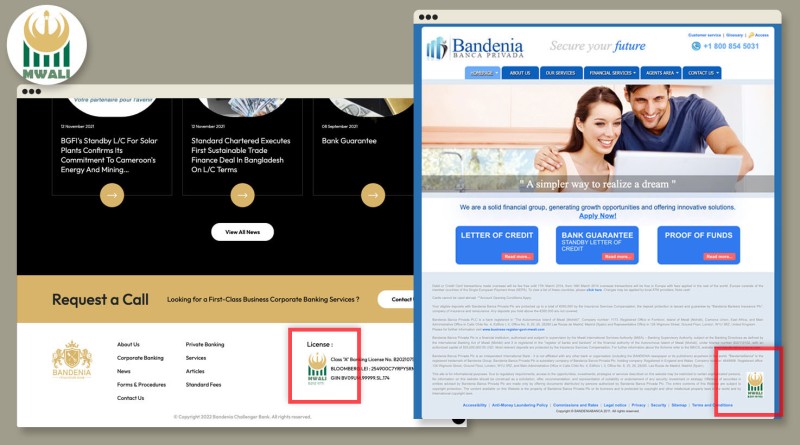

Bandenia Challenger Bank claims to offer “first-class business corporate banking services.” But OCCRP has learned that it’s really just a shell company that uses the word “bank” in its name. Its headquarters is a mailbox in London’s Hatton Garden neighborhood. The bank license it displays on its website, supposedly issued by the island of Mwali in the Comoros, is a fake.

Even the name “Bandenia” should have been a red flag.

In 2017, Spanish authorities cracked down on a group of around two dozen U.K. and Spanish companies operating as a fake bank — and also using the brand “Bandenia.” Centered around a U.K. firm called BBP Bandenia PLC, the firms had moved money on an “industrial” scale through Spanish banks for drug traffickers and fraudsters around the world, according to an indictment in the case, which is pending trial in Spain.

OCCRP reached out to Qureshi and Bandenia Challenger Bank for comment, but instead got a reply from the email address of a related company, also using the name “Bandenia.” The email, which was unsigned, did not directly address questions about Qureshi’s role in the company or its fake credentials, but it denied there was any relationship between the new Bandenia Challenger Bank and the older Bandenia firms.

The email insisted that Bandenia Challenger had simply bought the brand through an online consultant: “We just liked the trade name,” it said.

But OCCRP found that the two Bandenias share more than just a name.

Bandenia Challenger Bank’s fake license comes from exactly the same obscure jurisdiction — the Comoros island of Mwali — as one advertised on websites used by the previous Bandenia group uncovered in Spain.

Moreover, the man listed as the founding shareholder and director of Bandenia Challenger Bank was previously a director of BBP Bandenia, the U.K. company at the heart of the older operation that was targeted by Spanish investigators.

Bandenia Challenger Bank is not the only newer firm linked to the older Bandenia operation. As authorities clamped down, its former directors continued to set up hundreds of new shell firms in the U.K. and at least 12 other jurisdictions. Even BBP Bandenia’s former CEO — who was indicted in 2014 for laundering money through Bandenia, and convicted last year — got in on the action. Many of these firms are registered at an address above a tapas bar at London’s West End, just a short bus ride away from Bandenia Challenger Bank’s mailing address.

The extent of this newly uncovered group of companies has never been reported, and Spanish authorities said they were unaware of all the firms uncovered by OCCRP. There is no evidence that any of these shell companies engaged in money laundering, and it is not clear what most of them were used for, if anything.

A Spanish investigator who worked on the Bandenia case, speaking on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to talk to reporters, raised the question of whether the newly discovered companies might be the same operation reconstituted in a larger form. He called the new findings “of great interest.”

By 2017, a Google search for “Bandenia” would have revealed articles mentioning money laundering and its executives. Yet there appears to have been little interest among U.K. authorities in examining the group’s activities in their country.

“There was a meeting at Europol and we asked the British Serious Fraud Office to investigate [another Bandenia director],” the investigator said. “They showed no interest.”

The Serious Fraud Office told OCCRP it could “neither confirm nor deny any SFO interest in this matter,” and could not “provide any wider comment at this stage.”

The fact that people associated with the money laundering operation busted in Spain have started companies "under the same brand” in so many different countries is “really worrying," said Ben Cowdock of the U.K. chapter of the advocacy group Transparency International, adding that it “points to a lack of enforcement interest.”

The MP who had boosted Bandenia Challenger Bank, Docherty-Hughes, said he was resigning from the All Party Parliamentary Group on Blockchain after learning about Bandenia Challenger Bank’s background.

“I am deeply sorry that I may have inadvertently given them any sort of endorsement by allowing them to appear here,” he told OCCRP.

Identifying the Shell Companies

Reporters identified at least 450 companies registered around the world that can be linked to persons who were involved in the Spanish money-laundering operation. Only 27 of these had been named by the Spanish authorities. More than 240 others were registered after an indictment against people linked to Bandenia was handed down by a Spanish investigating judge in 2019. Another approximately 200 had been set up before that, but don’t seem to have been on the radar of Spanish authorities.

The First Fake Bank

At the old Bandenia operation’s former headquarters in the upscale Spanish town of Las Rozas, 20 kilometers outside Madrid, a Bandenia logo still hangs in the corridor outside its offices. But the light on the landing doesn’t work and the doorbell is broken. Nobody answers a reporter’s knock.

Though silent now, this was once a hive of activity. The fake bank is accused of moving money on behalf of an estimated 253 clients, most of them criminals, including drug traffickers, alleged fraudsters, and money launderers, according to a July 2019 indictment against 10 people and six companies linked to Bandenia. A trial is pending.

Bandenia allegedly used the shell companies, registered in Spain and the U.K., to open accounts at major banks, deposit money it received from its clients, and send it around the world.

In the indictment, Investigating Judge José de la Mata outlined how the firms functioned as a “shell bank,” using fake lines of credit and banking guarantees to justify the movement of cash between companies and individuals, and across borders. The investigating judge called the set-up "perfectly structured" for “industrial-scale” money laundering.

According to the investigating judge, between June 2012 and February 2015 alone, the main U.K. firm in the network, BBP Bandenia, moved at least 12 million euros in criminal money between various companies and banks. He also pointed out that BBP Bandenia had received millions in deposits from clients in Iran, a country under varying degrees of financial sanctions since 2010.

The Red Flags

Unlike many of the other companies identified by Spanish authorities, BBP Bandenia, the U.K. firm at the heart of the money laundering ring, appeared to do real customer-facing business and was not just a shell. However, the way it has conducted itself since its founding in 2003 should have raised red flags.

By the time the investigating judge finalized that indictment in 2019, BBP Bandenia’s former CEO, José Artiles Ceballos, had already been indicted in a separate case for using the company to launder drug money.

He had come to the attention of Spanish police in 2014 as they were investigating Ana Cameno Antolín, a major drug trafficker known as “The Cocaine Queen.” Investigators found that she was using the fake bank to send money to Panama for her Colombian drug suppliers. On the back of this, they opened a wider probe into Bandenia itself.

They found that Bandenia claimed to have a banking license from Mwali, one of the Comoros Islands, to create the illusion that it was a legitimate financial institution. (Later, in 2015, one of its affiliates obtained a real banking license from the Caribbean island of Dominica, although it was revoked in 2018.) Then, it assigned its clients account numbers and gave them paperwork similar to what a normal bank would provide — but all fake.

“Bandenia provides documentation and business structures that allow all kinds of criminal networks to move money,” said the Spanish investigator.

But how could a fake bank move real money?

According to the investigating judge’s indictment, shell companies linked to Bandenia would open accounts at major financial institutions like Spain’s CaixaBank and Ibercaja, as well as the Spanish branch of Dutch giant ING. Although the money deposited into these accounts was supposed to belong to their respective companies, Bandenia was actually using them to pool its clients’ funds instead — then sending the money around the world.

“Funds were sent through an electronic transfer to extraterritorial banks or companies … located in places where banking and corporate secrecy is strong enough to lose the traceability of the money," the indictment said.

ING declined to comment on its role in the scheme because of “ongoing legal procedures.” CaixaBank said it had been cleared of allegations of wrongdoing, which a court confirmed. Ibercaja did not respond to a request for comment.

The Other Bandenias

Though Artiles Ceballos might have been the main suspect in the Spanish investigation, authorities never believed he was acting alone.

“Artiles is someone’s man. He acts on other people's orders,” the Spanish investigator who worked on the case told OCCRP.

He added that investigators believed the fake bank had started as a “small-to-medium Spanish money laundering network” that was then “taken over” by others.

He did not elaborate, but OCCRP has found that three Italian men who held key positions in the companies named in the Spanish investigation continued to appear on the boards of similarly-named companies around the world, even after Artiles Ceballos’ arrest. (Reporters have not found evidence these companies were involved in any illegal activities.)

The most prolific was Fabio Pastore, the current CEO of BBP Bandenia, which still exists but is now in liquidation in the U.K. The U.K. High Court issued an arrest warrant for Pastore after he failed to show up in court in 2021 for a case involving BBP Bandenia. He has also served as director of dozens of other companies identified by reporters that have similarities to previous Bandenia companies. Two other Italian men, Massimiliano Arena and Giovanni Modafferi, are also former directors of BBP Bandenia who were listed as directors of other firms in the group discovered by reporters.

Neither Pastore nor Modafferi responded to requests for comment. Arena said that, while he had been a “Director of Bandenia,” he held “no executive and/or managerial position” and “never had access to any of the company’s information or documentation.” He said he could not answer any other questions about the firms he was listed as playing a role in.

Artiles Ceballos said that BBP Bandenia “had the appropriate financial licenses and was subject to the Money Laundering Regulations of the Office of Fair Trading.” He said he had known Pastore for years, as a financial consultant.

He added that “Bandenia Banca Privada had a permanent office in Madrid, but did not operate in the Spanish stock market and therefore was not subject to Spanish regulation. When asked about the wider group of companies discovered by reporters, he said, “All international companies diversify their investments and businesses.”

Serving Time, Keeping Busy

Despite being a convicted money launderer who has spent long stints in pre-trial detention since 2017, Artiles Ceballos has proven remarkably busy in U.K. financial circles.

As of April 2023, the ex-Bandenia boss, who was banned in 2014 from directing Spanish companies for eight years, is listed as the director of 185 British companies identified by reporters.

Company Directors Tied to Traffickers

Family members of Serbia’s Miodrag Stošić, a convicted human trafficker, were until recently listed as directors in U.K. companies linked to figures involved in the Spanish money laundering operation.

And Artiles Ceballos is not alone in this quest for new opportunities.

In 2019, a former corporate officer in BBP Bandenia became the initial shareholder and first director of a new company in the U.K. called Bandenia Challenger Bank.

This is the same company that Qureshi would use in late 2022 to get himself before the parliamentary working group, known as the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Blockchain.

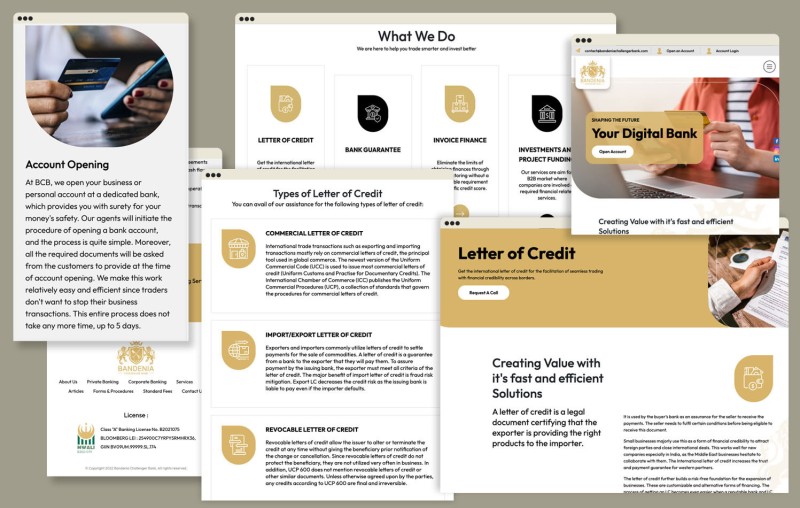

Despite its name, Bandenia Challenger Bank is not licensed to bank in the U.K., or anywhere in the world. However, on its website it offers letters of credit, bank guarantees, and other financial services that appear very similar to those once offered by BBP Bandenia.

People claiming to work for Bandenia Challenger Bank on LinkedIn are also using seemingly fake profile photos. Reporters found one profile, supposedly for the head of trade finance at Bandenia Challenger Bank, that used a generic corporate portrait from a stock photo website. Another profile, supposedly for a senior Bandenia Challenger Bank employee, used the image of a music professor at Washington State University.

An unsigned email from its sister firm, Bandenia Challenger Finance, responding to questions addressed to Qureshi, said it had simply bought the company name online.

“We don’t have any idea [about] BBP Bandenia and their group or what activity they have done in the past,” the email said.

Bandenia Challenger Bank’s website is emblazoned with a familiar symbol: a bogus banking authorization from “The Autonomous Island of Mwali (Mohéli).” BBP Bandenia — which claimed to be registered in “The Autonomous Island of Mwali (Mohéli)” in the Comoros islands — also boasted the same non-existent African license.

The Central Bank of the Comoros confirmed to OCCRP that the license was not real, and noted that it was aware of fake websites purporting to represent the country’s financial authorities — including a fake Mwali companies registry, which also prominently displays the same logo used by Bandenia Challenger Bank. The Central Bank is the only authority that can issue banking licenses in the nation, it said, adding that Bandenia Challenger Bank “is an offshore entity operating illegally with a fraudulent license.”

Bandenia Challenger Bank has also declared in U.K. corporate filings that it has an astonishingly high 180 million pounds in unpaid share capital — possibly a means of artificially inflating the company’s balance sheet. Another company directed and owned by Qureshi, London Trade Capital, declared 300 million pounds in unpaid share capital.

Cowdock, of Transparency International, said this was an accounting manoeuver that might give a company “a superficial veneer of legitimacy,” possibly making it easier to get bank accounts or take out loans.

Asked to comment on its fake license and share capital declarations, Qureshi and Bandenia Challenger did not respond directly, but the email from Bandenia Challenger’s sister firm noted that it was seeking funding.

“If you are looking for any money from our side you are looking at the wrong company,” it said.

“We don’t have money and are looking for seed funding to sell the shares and launch a tech product Banking as a Service model…

“[I]f you can find someone who is interested in funding a mortgage broker tech project, please let me know, We will be more than happy to connect.”