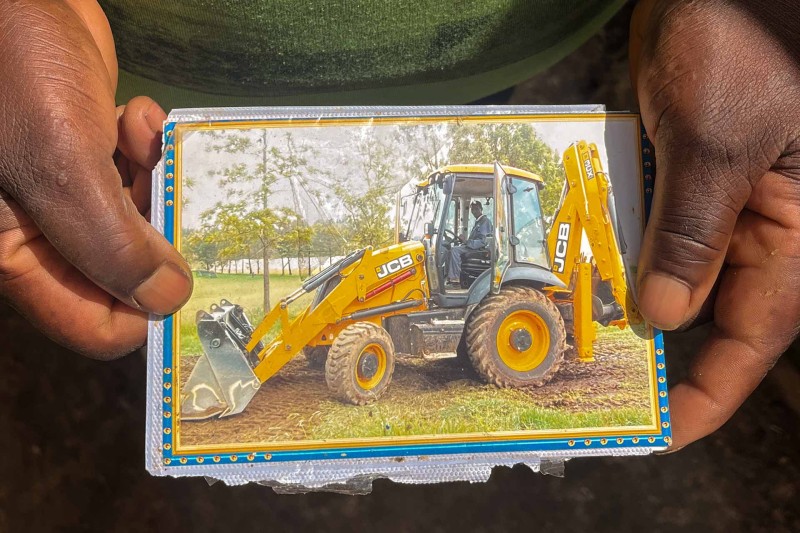

Tractor driver Wacharia Ngatia told his bosses at Ibis Farm, near Mount Kenya, that he didn’t know how to safely handle chemicals. They transferred him to work with the waste reservoir tank anyway.

“Within no time I started feeling itchy all over my body,” he wrote in 2004 in a letter to his employer, London-based Homegrown, now renamed Flamingo. Blisters started appearing on Ngatia’s hands and face, and he was continuously vomiting. But he kept working.

Ngatia died in his tractor seven years later. He was 53. His wife, Nancy, received the equivalent to US$300 from the company. She never heard from them again.

Nancy believes pesticides killed her husband, and is attempting to join a court case against the Kenyan government for allegedly allowing the licensing and manufacturing of such products.

Pesticide use has soared in Kenya over the last 30 years — and some of it is highly hazardous. On top of that, in February, the Pest Control Products Board (PCPB), raised concerns over the influx and use of unregistered and illegal pesticides into mainstream markets in the country.

Flamingo is the world's largest rose-grower and produces fruit and vegetables. They employ 11,000 people in Kenya.

“All pesticides used are taken from approved lists by our customers and all our produce is subject to rigorous checks and audits, in line with U.K. and EU retail trading standards,” Jennifer Renwick, representative for Flamingo told OCCRP in an email.

Ngatia had a “history of health complications which were not linked to his job,” Renwick said. She also said they have no formal death in service policy for employees in Kenya but confirmed Nancy, Ngatia’s wife, received over $300 as a “final payroll payment relating to his employment” and the company contributed funeral expenses.

Nancy Ngatia outside her home. (Photo: Georgia Gee/OCCRP)

Nancy Ngatia outside her home. (Photo: Georgia Gee/OCCRP)

The African Center for Corrective and Preventive Action (ACCPA), who filed the case in 2022, has petitioned the court to add more victims who have worked with pesticides to the case, which they believe could be in the thousands — given that the Kenyan agricultural industry employs 60 percent of the country’s workforce.

The Kenyan Ministry of Agriculture did not respond to a request for comment.

“Nobody is spared as long as these highly hazardous chemicals are in circulation,” said Kelvin Kubai, a lawyer with the ACCPA who is leading the case against the government.

It's not just the agricultural workers in Kenya that are impacted, the chemicals can be on anyone’s plate. A report released last September analyzing Kenyan produce identified Highly Hazardous Pesticides (HHPs) — which are banned in the European Union — in maize, wheat, coffee, potatoes, kale and tomatoes. The runoff of the pesticides also reaches nearby homes, schools and waterways.

Back in Timau, eastern Kenya, members of the community like Nancy Ngatia, want answers. She told OCCRP about her struggle to find out the truth around her husband’s death on Ibis Farm. Despite asking multiple times, she says that Flamingo has never given her the full medical reports.

“Life has been so difficult since he died,” Nancy said in her home. “We thought his job would give us a better life.”

Renwick told OCCRP, “Flamingo holds medical records for its employees and operates in line with our legal obligations both in maintaining and disclosing any records.”

Meanwhile, Flamingo’s business has been thriving: they achieved annual profits of £50 million (US$63.6 million) and paid one of their directors over £1 million a year, according to the company’s latest financial documents.

Similar stories to Ngatia’s were echoed by other former employees.

It’s been eight years since John Marangu, now 50, had to quit his job spraying pesticides at Ibis Farm. Now he can’t stop shaking. His hands, legs, and lips quiver constantly, and it's only getting worse. Both Marangu, and his daughter Jedidah, say that despite seeing doctors provided by the company, they were never given any diagnosis. Studies show that exposure to pesticides can increase the risk of neurological disorders in farm workers, including diseases such as Parkinsons. Marangu was ultimately fired from Flamingo, and said he never heard from the company again.

John Marangu in his home. (Photo: Georgia Gee/OCCRP)

John Marangu in his home. (Photo: Georgia Gee/OCCRP)

Renwick told OCCRP that “employees who work in this area receive regular medical check-ups and are issued with PPE (Personal Protective Equipment), as well as undergoing thorough training.” She said there is no record of any medical complaint or condition for Marangu, and his “employment was terminated via redundancy.”

For both Marangu and Ngatia families, life after Flamingo remains devastating.

“I want justice,” Ngatia told OCCRP, wiping back tears. “After my husband's death, my kids had to drop out of school. We have suffered.”