Taxi driver Wesam Shaath has become used to scouring the street stalls and shops of the southern Gazan city of Rafah for diapers for his twin baby boys.

Before the Israel-Hamas war erupted on October 7, 2023, he paid the equivalent of around $6 for a box. Now he says vendors can charge up to $55, which he cannot afford. In desperation, he has tried to make his own diapers for the twins.

“I tried to put ribbons and nylon on them, I tried more than one idea, but it didn’t work,” he told OCCRP. He struggles to afford even the most basic essential supplies for the babies, including formula milk.

The plight of Gaza’s civilians has been highlighted by the U.N. and multiple aid agencies — but the situation is getting worse. Gaza’s 2.3 million people are facing acute food shortages and half a million people there face “catastrophic levels of deprivation and starvation,” according to the deputy chief of the United Nations’ humanitarian agency, OCHA.

Palestinian refugees in Rafah wait in line to fill bottles and jerrycans with water.

Palestinian traders who spoke with OCCRP said the entry of commercial goods continues to be hindered by security checks imposed by Israel since the start of the war and constraints on movement, including multiple inspections, long queues at checkpoints, and devastated roads.

But from speaking with traders and officials, reporters found that multiple layers of profiteering compound the problem. They described a broken and exploited system where money is skimmed at every point in the commercial supply chain, from transport to procurement and sale, leaving Gazans with scant goods at sky-high prices.

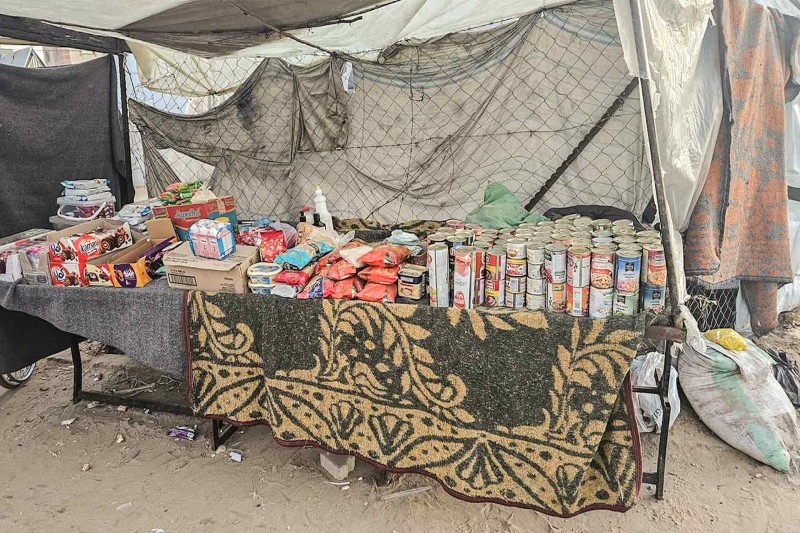

At the An-najmah market in Rafah, where street vendors display small quantities of goods including fava beans, sardines, tuna fish, lentils, sugar, juices, and sweets, shoppers and traders said the price of some food items had risen tenfold since the beginning of the war.

A market in Rafah, Gaza, in late February.

“Prices have increased tremendously,” said Hala Emran, a displaced mother of eight, after inspecting goods at the market. “Everybody is complaining, and many cannot buy anything.”

Hala said that she was unable even to buy a cookie for her young son, who is craving sugar. The cheapest one at the market is now selling for up to 10 shekels (approximately $2.70), compared to 1 shekel before the war, she said.

With much of Gaza reduced to rubble, the price hikes come as livelihoods collapse.

Wesam used to earn 30 to 40 shekels (between $8 and $11) in a day driving a taxi between Khan Yunis and Rafah, which is now crowded with 1.5 million displaced Gazans and under threat of an Israeli offensive. Since the war, his income has dried up.

“Things are very tough on us. Without income, I am unable to buy anything,” he said.

Traders Say Egyptian Transport Monopoly Charges ‘Quadruple’ Pre-War Prices

Before the war, aid trucks and commercial goods entered Gaza by two routes: the majority via the Kerem Shalom crossing with Israel and the rest via Rafah, which lies on the border with Egypt and was mostly used for civilian movement.

Roads and buildings destroyed in Rafah, Gaza.

Both crossings are intermittently open, but goods coming into Rafah are now diverted to Kerem Shalom first, unloaded, and checked before being taken back to Rafah to enter, creating queues and delays. Both humanitarian aid and commercial goods have slowed to a trickle and the costs of importing have skyrocketed.

Limited supply is one of the drivers of rising prices, but traders in Gaza accused an Egyptian company that is key to the flow of imports of piling on costs.

OCCRP reporters spoke with seven Palestinian traders, most of whom requested anonymity because they feared reprisals from Cairo, who said Egyptian logistics company Abnaa Sinai was profiting from an effective monopoly at Rafah.

Meat importer Eyad Albuzum said that before the war, Abnaa Sinai would already charge a minimum of $5,000 per truck but is now charging much more. “Prices have now quadrupled compared to before the war,” he claimed.

“Without going through them [Abnaa Sinai],” said another businessman, “you can’t take in anything. They were profiting from us before the war on the back of their monopoly, and they continue.”

A senior official at the Hamas-run ministry of economy, who spoke on condition of anonymity to avoid offending Egypt during a time of war, echoed traders’ accusations. He said that Abnaa Sinai had had an exclusive right to bring in goods and aid at the Rafah border crossing since 2018, but had piled on costs since the start of the war.

The official told OCCRP that according to traders he had spoken with, Abnaa Sinai had increased its prices sixfold and was also imposing a new charge of $75 per truck per day for waiting at the border for the security checks. If a trader wants to skip ahead in the queue, he also has to pay a bribe of up to $20,000, the official added. So between shipment charges, daily ground fees, and the bribe, the cargo could cost $40,000 just to get to Gaza.

Abnaa Sinai did not reply to questions sent by OCCRP.

Who is Behind Egyptian Transport Company?

In an ad on its Facebook page on November 15, Abnaa Sinai said that it was transporting fuel into Gaza “after efforts and complete coordination from the Egyptian state.”

Organi told Egyptian media at the end of October: “We are ready with all our resources; cars, equipment, medicine, and food. And when the opportunity presents itself, we shall help our Palestinian brethren with no hesitation.”

That help has been hard to discern. As supplies have dwindled, some hungry Palestinians have turned on each other. Trucks, mostly carrying U.N. relief goods, have been attacked and food consignments stolen.

Ismael Thawabteh, head of the Hamas-run government media office, added that trucks can wait on the Egyptian side of the border for 50 days.

Officials and Traders Blame Each Other for Price Hikes

As Gazans question why they can no longer afford even the most basic goods, each part of the commercial chain seeks to deflect blame for spiraling prices.

Officials argue that they are trying to implement a system that controls prices and accuse unscrupulous traders of trying to circumvent their controls to charge more. Meanwhile, traders accuse the Hamas-run authorities of undercutting them on prices and enabling a black market to flourish off the back of their goods.

Before the war, a company called Multi Trade, which one trader said was close to Hamas, was responsible for transporting goods from the Egyptian side of the border at Rafah to the Palestinian side, taking up to $500 per truck in “custom clearance” fees from importers. The Ministry of Finance also imposed between 3% to 4% in customs on merchandise, said the senior economy ministry official.

Multi Trade no longer operates and Thawabteh said that customs on merchandise are no longer imposed “in appreciation of the exceptional situation our people are currently exposed to.”

In a bid to control prices, a committee from the ministry of economy now buys the majority of each shipment from Palestinian importers, the senior economy ministry official said. Those products are taken to sales points run by the ministry in the three governorates of Rafah, Khan Yunis, and Central Gaza where prices are controlled, he added. The official blamed “traders, middlemen and thugs” for going around the system, trying to commandeer goods and hike prices.

However, traders who spoke with OCCRP said the Hamas-run authorities do not pay a fair price for their shipments and do not properly control prices at the sales points, fuelling a black market that puts basic goods beyond the reach of ordinary Gazans.

“The [economy ministry] takes the goods to selling points where goods are sold for unbelievable prices and no one adheres to the prices set by the ministry,” one trader told OCCRP.

“Imagine the ministry distributes to the selling points 10,000 trays of eggs. Traders who buy it, sell 2,000 or 3,000 trays, hide the rest and later sell them on the black market. The ministry of economy cannot control them by staying there until all goods are distributed and sold,” he added.

The official and traders described how, since the war started, Israel has imposed a new restriction whereby it authorizes only five Palestinian importers to transport goods into Gaza from Egypt.

The senior economy ministry official accused the authorized importers of taking up to a 30 percent cut from the Palestinian businesses receiving the goods.

Of the seven traders who spoke with OCCRP, three are among those now authorized by Israel to bring in commercial goods from Egypt to Gaza. They denied profiting from a monopoly, instead blaming Hamas-run authorities for seizing their goods and undercutting them.

One of the authorized traders told OCCRP he no longer felt able to operate in the Hamas-run system. “I am not willing to take the risk so that they make profits,” he said.

Basics Out of Reach for Ordinary Gazans

Gazans in Rafah ‘Staring Death In the Face,’ Says U.N.

The Israeli Ministry of Defense did not reply to OCCRP’s request for comment on the checks of shipments that traders say lead to delays.

Meanwhile, warnings from aid agencies of a complete collapse in Gaza become increasingly stark.

As commercial goods slow to a trickle and fewer traders want to face the costs and security risks of doing business, aid is also severely restricted, leaving Gazans destitute as the holy month of Ramadan begins.

People running toward humanitarian aid tracks in Rafah, Gaza.

A U.S. ship is headed to the Gaza coastline to build a temporary pier in an attempt to create a new route for food and medical supplies to come in from Cyprus, but it could be as long as two months before the facility is up and running, according to reports.

Last month the U.N.’s World Food Programme announced it was suspending aid deliveries to northern Gaza after some trucks were met by hungry crowds and gunfire.

The U.N. said there had also been “instances of Israeli strikes and naval fire hitting aid convoys and the security personnel accompanying aid missions in Rafah”.

In a statement in mid-February, Martin Griffiths, the U.N.’s humanitarian chief, described the Gazans crammed into Rafah as “staring death in the face: They have little to eat, hardly any access to medical care, nowhere to sleep, nowhere safe to go.”

Griffiths said the humanitarian response in Gaza was “in tatters.”

“Military operations in Rafah could lead to a slaughter in Gaza,” he said. “They could also leave an already fragile humanitarian operation at death’s door.”