Reported by

This week, four former employees of Kyrgyzstan’s leading investigative newsroom, Kloop, went on trial in Bishkek, accused of conspiring to “incite mass unrest.”

The defendants are an unusual mix: two accountants and two cameramen. All four have pleaded guilty, although their lawyer and Kloop management still insist the case was built on a false premise.

At a court hearing on August 5, prosecutors unveiled details of the indictment that few outside the defendants and their lawyers had seen — a departure from typical Kyrgyz criminal procedure. Kaisyn Abakirov, a Kloop lawyer who reviewed the document, said much of the case rests on five videos critical of the government, which prosecutors say the cameramen helped to produce.

But those videos were never published by Kloop at all. They appeared on Temirov Live, another investigative media outlet dismantled in a brutal crackdown a year earlier, and now operating from exile in a limited capacity.

The indictment also accuses Kloop’s accountants of transferring money to the cameramen for what prosecutors described as joint investigations with exiled journalist Bolot Temirov. The videos, critical of officials, were cast as attempts to “call for active disobedience to the lawful demands of representatives of authority and for mass unrest.”

Prosecutors accused Kloop of assisting in the production of videos made by Temirov Live, another Kyrgyz media outlet, from exile. Kloop denies having been involved.

Kloop denies that its staff ever worked with Temirov Live on the videos in question and says the trial is the latest stage in Kyrgyzstan’s sweeping assault on independent media.

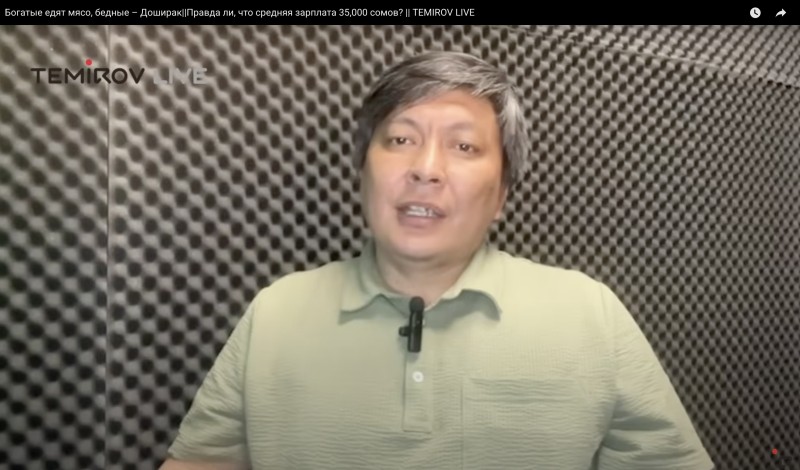

“The criminal prosecution is not linked to specific stories,” said Kloop co-founder Rinat Tukhvatshin. “In our case, there is not a single story in the indictment that was published on Kloop. [...] Kyrgyz authorities are simply finding any way to cause maximum harm to the media, the organization, and the people associated with it."

Kloop's co-founder, Rinat Tukhvatshin.

Officials have hardly hidden their intent. Earlier this year, a presidential spokesperson publicly accused Kloop of working with Temirov to carry out "special orders against the state" disguised as journalism.

Even Kloop’s leaders — who went into exile earlier this year — have been pulled into the dragnet. Tukhvatshin has been indicted in a separate criminal case, although his lawyer says he was never shown the indictment. He, editor-in-chief Anna Kapushenko, and executive director Galina Gaparova all had their bank accounts frozen this summer.

Kyrgyzstan’s Vanishing Press Freedom

Once referred to as Central Asia’s “island of democracy,” Kyrgyzstan has seen a notable backslide into authoritarianism under the presidency of Sadyr Japarov, a politician who rose to power after a popular uprising that brought down the previous government in October 2020.

When Journalism Becomes a Crime

Before Kloop, there was Temirov Live.

In January 2024, Kyrgyz security forces raided the newsroom in Bishkek, detaining 11 current and former journalists and staff, including the outlet's director Makhabat Tazhibek kyzy, who is also Temirov’s wife. All were charged with "inciting mass unrest.".

The timing was conspicuous: The arrests came days after Temirov Live released a video accusing Interior Minister Ulan Niyazbekov of abuses of power.

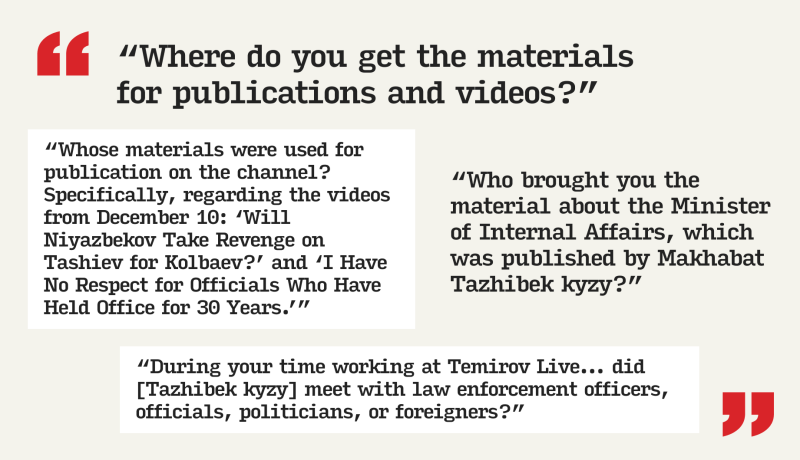

While officials denied the case had anything to do with the outlet’s reporting, court files reviewed by OCCRP suggest otherwise. Interrogation transcripts show officers pressed journalists about how stories were put together and who inside the government might be leaking information. They didn’t ask any questions about the supposed acts of incitement that the journalists were actually accused of committing.

Some of the questions asked during interrogations of Temirov Live journalists accused of incitement.

Ordinary newsroom routines like editorial meetings, editing videos, paying salaries were reframed as evidence of conspiracy. Employees were labeled "associates and assistants," while the use of encrypted messengers like Signal was described as evidence that journalists were "discussing negative topics aimed at inciting mass unrest.” In the prosecutor’s telling, the newsroom itself was the crime scene.

The case leaned heavily on linguists who were brought in by prosecutors to watch the videos and determine whether they really called for incitement, through methodologies that legal experts have called dubious. One analysis claimed Temirov Live videos contained "signs of calls for mass resistance, unrest, and eventual change in power." Another concluded there was "no direct incitement," but that the videos had a tone that could "influence public opinion in a destabilizing way."

Investigators also drew sprawling "interaction graphs" mapping Temirov Live’s sources, colleagues, and relatives, presenting them as a network of subversion.

The trial concluded in late 2024. Seven staffers were acquitted. Two young reporters, after eight months in detention, were released on probation. But two others received real prison terms: Tazhibek kyzy was sentenced to six years, and Azamat Ishenbekov to five. This spring, Ishenbekov was pardoned by the president, a reminder that Kyrgyzstan’s press freedom now depends on political whim.

Journalist Makhabat Tazhibek kyzy at her trial in 2024.

But the crackdown didn’t stop there The methods tested on Temirov Live would soon be streamlined and redeployed against Kloop.

A Tested Strategy, Reused

On a quiet Wednesday morning in May this year, 25-year-old Kloop reporter Ziyagul Bolot kyzy heard fists pounding on her door in the southern city of Osh. Within minutes, plainclothes security officers from the State Committee for National Security (GKNB) were inside, seizing her phone and laptop. She was told she would be taken to Bishkek for questioning, but no one explained why.

She was not the only one. That same day, the GKNB launched coordinated raids across the capital, detaining five more Kloop reporters and staff members. (Two more were arrested the next day.)

"People are being held incommunicado," said Kloop co-founder Tuhvatshin in a public statement that day. "They weren't allowed to call family or lawyers. I don't see this as a detention. I see it as an abduction."

Most were released within 24 hours, but soon reappeared in a video produced by the GKNB, and circulated on social media and national television, pledging to cut ties with Kloop and apologizing for their “destructive” activities.

Two cameramen, however, remained behind bars for months, while two Kloop accountants were banned from leaving Kyrgyzstan.

The authorities offered no specific charges at the time of the raids. Only later did it become clear that the case was tied to the five videos — none of them published by Kloop.

At the time, the GKNB issued only a press release accusing Kloop’s staff of "inciting mass unrest." The statement echoed the same vague language used in the case brought against Temirov Live.

Rights groups condemned the arrests as part of a larger pattern.

“Anyone who says something critical against the authorities or their actions is now regarded as calling for mass unrest," Syinat Sultanalieva, a Central Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch, told OCCRP. "This is a very dangerous trend in Kyrgyzstan because it resembles similar paths of development in neighboring countries."

For Kloop’s leadership, the message from the government has been unmistakable — but they say they will keep reporting, despite the pressure.

"We will continue our work,” said Tukhvatshin. “We won’t stop producing investigations. [...] Since no one can do this in Kyrgyzstan, we will be the ones to do it."

Two Kyrgyz journalists who cannot be named for security reasons also contributed to this story