The Chinese tech giant Huawei signed deals to make large payments to two men close to Serbia’s state telecommunications company, using offshore companies that financial crime experts say raise red flags for corruption.

One of these men, former Telekom Srbija executive Igor Jecl, appears to have received over $1.4 million in contracts, dividends, loans, consulting fees, and an apartment from an offshore company that was paid by Huawei for consultancy.

Neither offshore company that dealt with Huawei has a public track record of doing consulting work, or any business at all.

“It is standard with bribery and corruption to dress them up as consultancy,” said Graham Barrow, an expert on financial crime.

Although OCCRP has not uncovered evidence that the payments were improper, they were made over a period of time when Huawei was doing business in Serbia. In 2016, it landed a 150-million-euro deal to upgrade Serbia’s telecommunications infrastructure.

Reporters found out about the deals through The Pandora Papers, a leak of nearly 12 million documents from 14 offshore service providers obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and shared with news organizations including KRIK and OCCRP. They provide an inside look at how the wealthy and powerful hide money in secretive jurisdictions like Panama and the British Virgin Islands.

The papers suggest that Jecl wasn’t just dealing with Huawei on his own, but tapping into an existing offshore structure set up by another person: Milorad Ignjačević, a prominent Serbian lawyer who had business ties to Telekom.

Pandora Papers documents only provide a brief snapshot of how Jecl’s and Ignacevic’s companies operated, but among them are multiple invoices showing planned payments to the offshores, justified by contracts with Huawei.

Together, the two companies had at least six such contracts, for which they issued invoices to collect at least 947,399 euros (about $1.1 million). Four of the contracts were handed over from one of their shell companies, in Panama, to another one in the British Virgin Islands, for reasons that were not explained.

The Pandora Papers include the full details of only one of these contracts. Signed on January 1, 2014, it stipulates that the consultant would be paid 359,000 euros (over $493,000) to organize meetings for Huawei with Serbian telecom officials and executives.

The consultant is also asked to help Huawei obtain approvals and licenses, and “urge the Customer [Telekom] to make the payment to Huawei timely and promptly.” Another document in the Pandora Papers shows that the contract was fulfilled, and the 359,000 euros were paid.

The Limitations of the Data

The new revelations about the Serbian deals come amid widespread distrust of Huawei, which is pitching its 5G networks around the globe. Australia, the U.S. and the U.K. have all banned Huawei from building 5G infrastructure for fear that China could use it for spying. U.S. officials have pointed to the military background of Huawei’s founder, Ren Zhengfei, while the company has stated that it "would categorically refuse to comply" with any orders to spy.

Amid a Chinese push to extend its political influence into the Balkans, Telekom Srbija — where Jecl was a department head from 2005 to 2008 — began purchasing equipment from Huawei in 2006. A decade later, the two companies signed a 150-million-euro deal to overhaul Serbia’s communications network under terms that remain opaque.

Vladimir Lucic, the current CEO of Telekom, said he had been completely in the dark about the consulting arrangement, and was not aware of any consulting having been done. He called it “shocking.”

“That is unnecessary and it is shameful,” he said. “Both Huawei and Telekom wouldn’t have needed that because they are two big multinational companies.”

Experts in illicit finance told OCCRP that Huawei’s offshore arrangement with Jecl and Ignjačević raised red flags.

Barrow said the set-up was “similar in all respects to others that I’ve seen that were set up solely for the purpose of receiving bribes.”

“I am not going to say this is definitely bribery,” he added, “but it is very hard to distinguish.”

Ross Delston, a Washington, D.C.-based anti-money laundering specialist, said the amounts being paid to the offshore companies for consulting also seemed unusually high.

“It’s a lot of money for a consulting contract, a lot of money,” he said. “No question that’s odd. The ownership of the companies is odd. Why not use a Serbian company? ”

Jecl, now 56, joined Telekom in 2005 after spending two years as an adviser to the company’s former CEO, Drasko Petrović, who has ties to the Democratic Party of Serbia. He was seen as an innovator at the state company, where he was involved in major projects to bring broadband internet and internet radio to Serbia. But he resigned in 2008 and disappeared from the public eye.

“I haven’t had any contact with him since he left Telekom,” said Lucic, the former CEO.

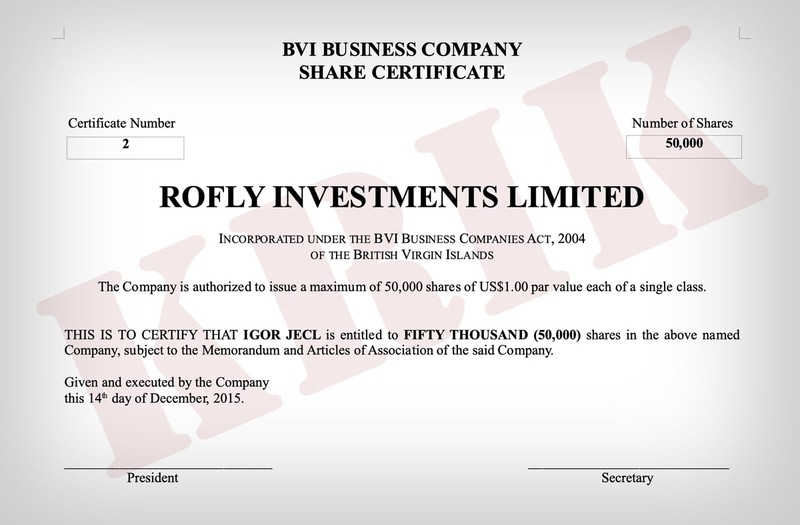

Now, his name has resurfaced in the Pandora Papers — among documents leaked from a law firm in the British Virgin Islands, where he became the owner of a shell company called Rofly Investments Ltd. in December 2015.

A British Virgin Islands Mystery

Rofly had been set up in 2011, but was originally owned by another shell company based in Panama, where corporate secrecy laws make it difficult to know who was behind it.

This layered ownership structure is a common tactic to obscure the identities of the people behind a company, Delston said.

“The two companies in different offshore financial centers, one owning the other, is a form of layering of beneficial ownership to further ensure anonymity,” he said.

In the years between when it was set up and when Jecl took over, Rofly had already received 650,000 euros (around $768,000) from Huawei. It had no other known business.

Jecl, in turn, made agreements to receive large sums of money from Rofly even before he owned it, suggesting he had a pre-existing relationship with the company.

In early 2015, Rofly agreed to pay him 50,000 euros ($56,421) for consultancy. Later that year, the company said it would loan him 250,000 euros ($265,376) to set up a chain of ice cream shops in Spain, according to a draft agreement and business plan found in the Pandora Papers.

Just three days before Jecl took over Rofly, the company received four more consultancy contracts with Huawei in an unusual way — they were transferred directly to Rofly from a shell company in Panama belonging to Ignjačević, the lawyer with ties to Telekom

This meant that, seemingly out of nowhere, Jecl became the owner of a company that held at least five contracts to consult for Huawei.

The earliest of these was inked in 2007, two years after Huawei opened its first office in Belgrade, on the vanguard of a wave of Chinese investment that has poured into Serbia since then. The Balkan state has become a cornerstone of Beijing’s efforts to expand its financial and political influence in Europe with the encouragement of Serbian President Aleksander Vučić, who frequently publicly praises the Chinese government and its local investments.

As one of China’s biggest tech companies, Huawei’s influence in Serbia has risen in tandem with Beijing’s. In addition to its deal with Telekom, the Chinese firm is working with Serbian police to install nearly 1,000 high-tech facial-recognition cameras across Belgrade. This “Safe Cities” project has sparked concern in the EU over China’s export of so-called “digital authoritarianism,” and led to an outcry among privacy advocates and many ordinary Serbs who see it as dystopian and intrusive.

The company has also faced allegations of bribery in countries including Ghana, the Solomon Islands, and Algeria. In a 2018 report, the Washington, D.C.-based consulting firm RWR Advisory said it had tracked seven Huawei deals reportedly marred by corruption allegations, worth a total of $5.1 billion.

Huawei declined to comment to reporters for this story, saying only: “Unfortunately, we are not aware of the matter to which you are referring.”

Tracing a Panama Company Back to Serbia

Goldberg Brokerage, the Panama-based company that handed the Huawei contracts to Rofly, was able to conceal its owner due to the Central American nation’s corporate secrecy laws.

But it did publicly report its officers. Journalists noticed that its director and treasurer was listed as Ignjačević, the lawyer whose family firm has been a Belgrade fixture since 1945.

Ignjačević and his family also had business ties to Telekom, reporters have learned. (See box)

Ignjačević’s Lucrative Links to Telekom

Now retired, the 84-year-old lawyer was courteous and forthcoming in an interview at his office in Belgrade’s central Vračar neighborhood. But he grew visibly frustrated after being asked detailed questions about his offshore holdings, and contradicted himself at several points.

He quickly volunteered that he was the owner of Goldberg Brokerage as well as its director, but said the offshore company didn’t do any business.

“Its purpose was to be a means for future businesses,” the lawyer said. “It was founded with the hope that it would get some work in future.”

However, when reporters asked him about Goldberg Brokerage’s contracts with Huawei, he said he suddenly remembered that Huawei had paid him through the offshore company for advisory work.

“Huawei had been there [in Serbia] for two, three years, trying to get some business,” Ignjačević said. “Then, I helped by advising them.”

When he asked if he lobbied on behalf of Huawei in Telekom, he said: “For sure, I did. If anyone from Telekom asks what my opinion is about Huawei, I will for sure say, ‘Take Huawei.’”

He also presented himself and his son as “good friends” of Jecl, and described the former Telekom director in glowing terms as “a top expert, a man ahead of his time.” But after being asked detailed questions about Jecl, Ignjačević backtracked and insisted they were no longer in touch.

He said he was appalled to hear that Goldberg’s contracts with Huawei had been transferred to his friend’s offshore company.

“This is news to me and unfortunately shocking,” he said. “I had no idea that there was a company [called] Rofly, nor that a contract had been concluded under which Rofly would take over my Goldberg business. These are all total forgeries or fabrications.

“It would be devastating for me if you were proven right in everything … because that would mean that my acquaintance — I wouldn’t say ‘friend’ — Igor Jecl, is the most common liar and forger.”

Finding Igor Jecl

Jecl’s life today is a far cry from his years heading to work at Telekom Srbija’s boxy concrete headquarters in Belgrade. He now lives in Sotogrande, an upscale private community on Spain’s sunny Costa del Sol.

There, he owns an ice cream company called “Daddy Cool,” as well as at least two shops selling gelato under the brand name Eccolo.

Eccolo Gelato’s stores, in Sotogrande and Madrid, garner rave reviews on TripAdvisor and Google for their affogatos and scoops in flavors like banana, cinnamon, and dulce de leche.

On its Facebook page, Eccolo boasts that it has been making gelato since 1912, using “recipes developed more than 100 years ago by Schiavi family in Almenno San Bartolomeo, the picturesque Italian village near Bergamo.”

But while the recipes may be ancient, the company is not. According to the Spanish business register, Jecl started Eccolo in 2016 — apparently with the 250,000 euros loaned to him by Rofly Investments.

Although the ice-cream shops have an extensive social media presence, Jecl himself is harder to find. Repeated attempts to reach him for comment, both directly and through his business, were unsuccessful. He no longer appears to maintain an address in Serbia, and his British Virgin Islands company has been shut down.

However, reporters did find traces of Jecl in another tropical destination.

Documents found in The Pandora Papers reveal that he owned yet another offshore company in the Bahamas, Topville Investment.

Topville doesn’t appear to have conducted any business, but a few months after it was set up in 2014, it was given the purchase contract for a luxury condo under construction in a gated complex on the north coast of Nassau, the most populous island in the Bahamas. It’s not clear how much of the contract was paid off, but a year later Jecl sold the condo for $490,000.

Again, the contract came from Rofly Investments, the mysterious offshore company that signed contracts to consult for Huawei.

Like Rofly, Topville is no longer active — it was dissolved in September 2017.

The only reason given for shuttering the company? “It has no further use.”

.jpg/daf5f209c20846c8dcd2295cae2a00ae/kenyan-aladdin-sep24-(1).jpg)