A collection of documents leaked from a secretive offshores services firm in Panama shines a light on how some Czech business operatives were clandestinely linked to others in some of the country’s more notorious financial scandals.

Details about these transactions are buried in the Panama Papers, a trove of internal data of Mossack Fonseca, a Panamanian legal firm doing business in offshore tax havens for clients who want to hide their identities and/or holdings.

The data was obtained by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists with the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and more than 110 media partners from 82 countries.

One of those partners is the Czech Centre for Investigative Journalism (CCIJ), which focused on offshore companies connected to other businesses or people from the Czech Republic.

On March 7, 2012, a Czech citizen named Lukas Macku contacted Mossack Fonseca in order to start a new company called Old Touch Ltd.

The office address was to be the “standard address of Mossfon companies,” that of the new director, Cyprus resident David Demetrios. The company's authorized capital was small: US$ 50,000, divided into 50,000 shares, held by someone unknown.

So far, nothing to attract attention. But not for long.

About a year later, at the end of June 2013, Macku contacted Mossack Fonseca again. This time, “the client wanted to increase the authorized capital of Old Touch from US$ 50,000 to US$ 13,100,000,” a staggering increase.

Such a maneuver is not uncommon in offshore jurisdictions, where unknown owners can shift funds rapidly through a series of companies before abruptly siphoning out the cash. In one scenario, a corporation with an inflated (fake) value on paper is used as collateral for a loan of real money, which then moves through a trail of paper companies before disappearing into someone’s pocket.

According to emails exchanged between Macku and Mossack Fonseca, two and a half months after the huge increase in Old Touch capital, the company had a new owner: Martin Benda, a businessman connected to several large and notorious insolvency cases in the Czech Republic.

Benda was a leading figure in the financial machinations surrounding the Kotva shopping center, one of Prague's most prominent early malls, and the Trend funds, an investment fund formed during the chaotic days of privatization during the 1990s.

Benda was a representative of Forminster Enterprises Ltd., a company from Cyprus that obtained 55,46 percent of Kotva's shares from the Trend Funds. But the contract was written in such a way that Forminster did not have to pay for the shares for years.

The Trend Fund, like others at the time, transferred fund assets to one or more offshore companies, draining clients’ deposits and sending them in untraceable directions. The Trend fund eventually collapsed and went bankrupt. Some fund employees were convicted but the case was dropped in 2014 with the president issued amnesty in 2013; Benda was investigated by the police but never tried.

But the chain does not end with Benda.

Elsewhere in the documents, CCIJ found a company called Gotrade Systems Inc., this time based in Panama. A familiar name popped up: Lukas Macku, this time linked with another Czech citizen, Pavel Petrovic. There is little doubt that the two know each other: they are friends on Facebook.

Both Macku and Petrovic were also involved in the case of WPB Capital, another bankrupt fund story and one of the most serious in the Czech Republic's recent history.

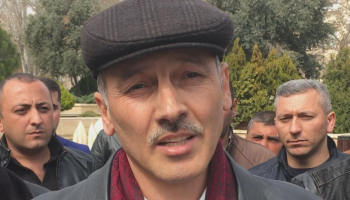

WPB Capital was one of the largest Czech savings funds. Family members of Petrovic were among its founders, and for years he was one of the people in charge of the fund. According to the management of WPB Capital, a conflict between Petrovic and his colleague, Patrik Bugan, ended with Petrovic leaving the fund in 2009.

Management claims Petrovic left angry, and made up his mind to destroy the fund.

In June 2014, the Czech National Bank (CNB) revoked WPB Capital’s license, stating that the fund deliberately used a network of companies to artificially inflate its capital and conceal its real financial situation.

And that is where Macku comes into play.

At the end of April 2014, two months before WPB’s license was revoked, a company called Tapovan s.r.o. filed an insolvency suit against WPB Capital, seeking to get it declared insolvent. Tapovan, both run and directed by Macku, had received a 96 million Czech koruna (nearly US$ 4 million) loan from WPB in 2011 to buy a promissory note from J&T Private Equity B.V. The loan seems to be the only significant thing Tapovan ever did.

The note was allegedly supposed to be collateral for the money borrowed by Tapovan. Tapovan claims that WPB received money resulting from the ownership of the note, more precisely around 103 million koruna (US$ 4.26 million).

In short, Tapovan accused WPB Capital of having kept more than it had a claim to, and filed the insolvency case. WPB Capital accuses Petrovic of secretly controlling both Tapovan and Macku and trying to destroy the fund through fake claims. The case, now almost two years old and dragged through several courts, is still unresolved.

Although no criminal activity has been proven, the Panama Papers are invaluable in analyzing connections between offshore companies and the people involved in them. Further investigation is necessary.