The Odebrecht corruption case has been a fixture of headlines for years in Guatemala, where the scandal-plagued Brazilian construction company was forced to repay over $17 million to the government after admitting that it bribed officials to gain a lucrative contract to renovate a major highway.

But another player in the case has largely escaped public scrutiny: the highway’s major financier, the Central American Bank for Economic Integration, or CABEI.

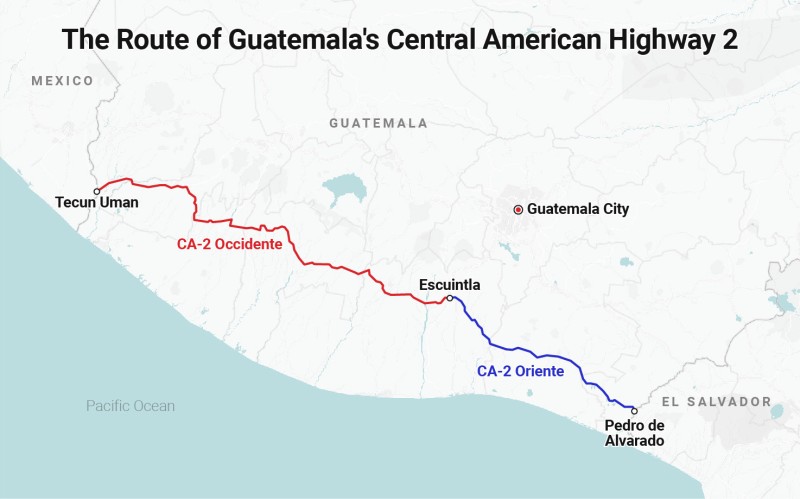

The bank provided the key loan to Odebrecht that allowed the project to move forward, agreeing in 2011 to lend almost $120 million to finance the longest section of Central American Highway 2, which would link El Salvador to Mexico.

Along the way, it overrode its own procurement rules to insert a clause in its loan agreement mandating that Odebrecht must receive the contract to build the highway, without the normal bidding process. Later, Odebrecht paid out millions in bribes directly from the money CABEI disbursed, according to an investigation by a UN-backed anti-corruption commission.

“Much of the corrupt diversion of funds from [CABEI’s] loans continues to be unaddressed due to the opaque and secretive policies that the bank applies to civil society groups and justice institutions that seek to know their final destination,” said Manfredo Marroquín, the president of Transparency International’s Guatemalan chapter, Acción Ciudadana

The Guatemalan minister accused of personally receiving the largest chunk of the bribe money, Alejandro Jorge Sinibaldi Aparicio, turned himself in in 2020 after four years on the run. He then made an explosive statement to prosecutors that also accused a CABEI official of conspiring with Odebrecht to make sure the highway contract would be favorable to the company.

While Sinibaldi’s testimony was widely reported, his comments on CABEI were not.

But OCCRP and its Guatemalan partner, No Ficcion, can reveal that Sinibaldi described working with Odebrecht’s chief of operations to lobby CABEI, and traveling with him to Honduras to meet with top bank officials.

The former minister said that CABEI was “fundamental” to the bribery scheme, and accused Odebrecht of paying a senior figure within the bank $500,000 “for his services” in getting the final steps of the loan approved. (Reporters were unable to find documentary evidence that such a bribe had been paid or offered.)

Juan Francisco Sandoval, the former head of Guatemala’s Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Impunity (known by the Spanish acronym FECI), told reporters his office had started investigating the allegations of bribery within CABEI after Sinibaldi gave his testimony. But the probe was upended when Sandoval was fired in 2021 and forced into exile amid a crackdown on anti-corruption officials.

FECI did not respond to questions about the status of the investigation.

Guatemala’s Long Road to Justice

Since October, thousands of Guatemalans have taken to the streets in protest against the Public Prosecutor’s Office’s interference in democracy and to demand the Attorney General’s resignation.

Sinibaldi — who was blacklisted for “significant corruption” by the United States while a fugitive — is currently awaiting trial in Guatemala related to this and several other alleged corruption schemes. He has since claimed he never made a statement to prosecutors at all, telling OCCRP that his testimony had been fabricated in order to generate conflict between him and “important political actors, public officials, and congressmen of Guatemala.”

However, the current administration of FECI confirmed to reporters that, despite Sinibaldi’s claim, he did indeed give the testimony obtained by No Ficción. Three sources close to the Odebrecht case also confirmed that the former minister gave the testimony.

The allegations against Odebrecht in Guatemala are part of one of the largest corruption scandals in Latin American history. After building some of the region’s biggest infrastructure projects, from capital city metro lines to World Cup stadiums, Odebrecht became the focus of Brazil’s Operation Car Wash corruption probe, and its dedicated bribery department became emblematic of its excesses.

In 2016, the U.S. announced the company would pay $2.6 billion in penalties for orchestrating bribery schemes to obtain government contracts in a dozen countries. Everyone from presidents to lawyers has been imprisoned for colluding with Odebrecht, while the company’s chief executive was jailed for 19 years for bribery, money laundering, and organized crime.

CABEI did not respond to requests for comment.

A ‘Historic’ Exception

CABEI agreed to lend $119.4 million to co-finance the highway’s longest section — the CA-2 Occidente, or CA-West — in August 2011.

However, its resolution on the funding contained an unusual clause: an exception to the bank’s own procurement policies that allowed it to name Odebrecht as the contractor for the highway right away, rather than putting the project up for public bidding.

“... as an exception to the Policy for the Obtaining of Goods and Related Services and Consulting Services with CABEI Resources and its application regulations, the project to be financed will be executed by the company Constructora Norberto Odebrecht, Sociedad Anónima.”

In other words, CABEI would only fund the project if the contract was awarded to Odebrecht — even though this was against both the bank’s normal policies and Guatemalan law. In the resolution, this is explained as necessary so that the project can be co-financed by the Brazilian development bank BNDES. Neither CABEI nor BNDES responded to questions on the clause.

Marroquín, of Acción Ciudadana, said the clause was a significant irregularity for such a large development bank.

Preemptively awarding the contract to one company is “obviously a practice far removed from any principle of integrity and competence,” he said.

After CABEI had agreed to the loan, the contract still had to be approved by Guatemala’s Congress. In his testimony, Sinibaldi described that task as “titanic,” since it was illegal in Guatemala to hand such a major public work to a company without a tender.

He described working behind the scenes along with other government officials to push through decrees and memoranda that could circumvent the need for a bidding process. On October 11, 2012, Guatemala’s Congress approved a government decree to designate the highway a matter of national urgency, meaning the loans would be signed off in a single vote the same day.

The decree flouted the public bidding process and reduced oversight of the project to a minimum. In his testimony, Sinibaldi called the congressional approval “historic.”

In parallel to the Guatemalan approval, CABEI’s loan contract went through multiple stages of negotiation, and was changed both before and after it was signed in November 2012.

Sinibaldi told prosecutors that he and Marcos Machado, Odebrecht’s chief of operations at the time, had already been meeting about the highway project that year. When Oscar Pineda Robles was appointed as the country’s new director for CABEI in September 2012 they identified him as a person who could help as they worked to ensure the contract was drawn up according to plan. A lawyer by trade, Pineda was well-connected, having previously served as Guatemala’s minister of economy, vice minister of finance, and president of the central bank.

In the testimony that Sinibaldi told reporters was fake — but which Guatemala’s Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Impunity confirmed he gave — he said that he visited Pineda at his home in 2012 to discuss the highway.

“I explained to Oscar [Pineda] the importance of counting on his support and, when the time came, [for him] to lobby CABEI’s board of directors over the final steps,” Sinibaldi told prosecutors. “Oscar mentioned that he’d already met with Marco Machado.”

Sinibaldi testified that Pineda later told him that Machado had offered a large sum of cash in exchange for his help, Sinibaldi claimed.

“Returning to the management of the project’s approval, I have to say that the final steps in CABEI weren’t simple, and the role of Oscar Pineda Robles was fundamental,” Sinibaldi said to prosecutors. “On one occasion at Pineda Robles’ home, he told me that Odebrecht’s representatives had offered him $500,000 for his negotiations in the board of directors, and he indicated to me that another $500,000 would be necessary to buy some goodwill of those they lacked inside the board due to the loan’s complexity, so he asked me for support to convince Machado, a situation about which I chatted to Machado.

“Later on, after CABEI’s process had concluded, Pineda Robles told me that everything had come out marvelous and that Machado had complied with just what was needed," he told the prosecutors.

He testified that Machado also told him that Odebrecht had paid Pineda $500,000 “for his services.”

Reporters were unable to independently verify whether Pineda received payments from Odebrecht. Machado and Odebrecht told OCCRP they were unaware of any bribes to or illicit dealings with CABEI employees. Pineda denied participating in the negotiations over the loan and told OCCRP that he had never met with Sinibaldi or with anyone from Odebrecht.

“I categorically deny having received any gift, remuneration, compensation, payments, gifts, bank transfers or sums of money from Constructora Norberto Odebrecht … for any reason,” he told OCCRP in an email.

“I’ve never had any link or relationship with the aforementioned Brazilian company,” he added in a follow-up email. “EVERYTHING MALICIOUSLY ATTRIBUTED TO MY PERSON BY THAT REPROACHABLE AND PERVERSE CHARACTER [SINIBALDI] IS, WITHOUT EXCEPTION, AN ABSURD LIE.”

He added that in his role as a CABEI director he had limited decision-making power — besides a single vote to approve a given project — and reviewed neither loan conditions nor modifications. He said the final approval for those things lies with the bank’s governors, country manager, and president.

However, CABEI’s former president, Dante Mossi, said directors have significant decision-making powers inside the bank. “Contract modifications require a change of procurement plan — those changes are Board approved,” he said.

A businessman who has been implicated in one of Sinibaldi’s alleged corruption schemes — who spoke on condition of anonymity due to the ongoing legal cases — said that Odebrecht executives spoke of having “secured” CABEI.

Sinibaldi denied the charges against him, but told reporters he could not discuss the details of the allegations because the case is ongoing. He also denied ever having met Pineda, or discussing bribe payments with Pineda or Machado.

The Other End of the Road

Just over two weeks after CABEI signed the contract to finance the CA-2 Occidente in late 2012, the development bank approved another $280 million to improve and expand a 100-km section of the highway that reaches the Salvadoran border in the east, known as the CA-2 Oriente.

Rising Costs

In Machado’s own testimony given to prosecutors on the case, he described a long series of negotiations with various officials on what clauses the contract would contain. He listed half a dozen changes to the draft that had been requested by Sinibaldi’s ministry, including additional bridges, lanes, and asphalt calculations, which inflated the cost by more than $14 million.

Each of the changes had to be approved by the two development banks financing the project, according to Machado’s testimony and documents seen by reporters.

Even after Guatemala’s government signed off on the loan, additional changes to the project’s cost continued to be pushed. In Sinibaldi’s testimony, which he has since denied giving, he recounted a drunken dinner in Miami in October 2013 with Machado and other businessmen from Guatemala’s construction industry, during which they offered him a significant bribe if he approved raising the project’s cost by a further $250 million.

“‘Who would finance the work?’” he recalled asking. “Machado answered that they already had CABEI aligned; that they wouldn’t oppose it and would give the financing.”

Though Sinibaldi told prosecutors in his testimony that he refused their proposal, six modifications to the contract were approved and pushed through by the government one month later, according to documents obtained by No Ficción through freedom of information requests.

Among them were additional budget items, changes to the prices of the planned works, and an amendment to Odebrecht’s advance — now 20 percent of the total project, totalling $73.6 million — to be paid out of CABEI and BNDES’ loans. CABEI issued “no objection” to all these modifications in November 2013.

Neither Machado nor CABEI responded to requests for comment on this incident.

CABEI transferred its first disbursement of $38 million to Odebrecht in April 2013. In his testimony to prosecutors, obtained by reporters, Machado said the first seven payments Odebrecht allegedly made to Sinibaldi and two other senior public officials were paid from this initial tranche of cash from the development bank.

In their conclusion to an investigation into Odebrecht’s bribery, Guatemalan public prosecutors and investigators from the U.N.-backed CICIG said this “synchronization” of loan disbursements and payments was repeated with every tranche of funding Odebrecht received from CABEI and the Brazilian development bank.

The Risk Officer’s Novel

The multiple scandals related to highway projects funded by CABEI bear a striking resemblance to a subplot in a book entitled “The Organization That Fights Against Poverty.” Self-published in May 2021, the novel was written by Diego Fiorito, who was CABEI’s chief risk officer at the time of Odebrecht’s alleged corruption schemes.

"The banks CABEI and BNDES made the disbursements to Odebrecht, which in turn transferred the agreed bribes,” they wrote. They also found Odebrecht sent $17.9 million to offshore companies belonging to Sinibaldi and two other political figures between 2013 and 2015. These findings were forwarded to a judge and formed the basis for the pending case against Sinibaldi.

The development of the CA-2 Occidente highway ground to a halt as the U.S. closed in on Odebrecht’s sprawling corruption scheme and its reach into Guatemala. CABEI stopped financing the project in early 2017, after giving a total of $85.5 million to Odebrecht, the Guatemalan public finance minister told local media at the time.

In 2018, as part of a court settlement in Brazil, Odebrecht agreed to return the exact amount that CICIG and public prosecutors found it had paid in bribes — $17.9 million — to the Guatemalan state. Four people are already in prison for their part in laundering money from the scheme. But the cases relating to Odebrecht have been hampered by repeated crackdowns on the independence of Guatemala’s justice system.

Odebrecht — now renamed Novonor — told OCCRP that it has filed an appeal over more than $45 million the company says it is owed by the Guatemalan government for the work done before the contract was terminated.

Meanwhile, after years of work and hundreds of millions of dollars spent, the redevelopment of Central American Highway 2 remains incomplete. People who live nearby have complained about the state of the road, which they say is in terrible condition and causes accidents.

Local media reports describe multiple accidents caused by huge potholes. One bus driver told the magazine Con Criterio in 2018 that some of the holes can be up to two feet deep, and can take out a car’s clutch.

“So many people have died in accidents that the highway’s become a cemetery,” said Marroquín. “It’s not only that they stole money, it’s that they left behind a death trap.”

Eduardo Goulart de Andrade (OCCRP), Andrew Little and Mariana Castro (both Columbia Journalism Investigations) contributed reporting.