Facing 130 years in prison, infamous Turkish-Iranian money launderer Reza Zarrab took a plea deal in 2017 agreeing to testify in U.S. courts. Federal officials have since kept him out of the spotlight, while allowing him to live a government-sanctioned life of luxury under a false identity in Miami.

But the man who made his fortune cleaning profits from sanctions evasion and dealing with companies tied to slave labor and organized crime has been anything but idle.

An investigation by OCCRP, Law&Crime and the Miami Herald found that Zarrab remains connected to his former criminal network and has received multiple questionable wire transfers from Turkey. Using fake identities, he’s invested in thoroughbred horses and a palatial equestrian facility, entering an industry rife with fraud and money laundering.

U.S. officials declined to comment when asked if they have concerns about his activities or if he’s surrendered a dime of his fortune.

Dubbed the “The Turkish Gatsby” for his playboy lifestyle, Zarrab ran a vast money laundering operation that channeled funds to Iran, in violation of U.S. sanctions against the Persian Gulf country. U.S. prosecutors offered a conservative estimate that his network moved at least US$20 billion from 2010 to 2015 alone.

Reporters tracked Zarrab, 38, to Miami’s Coconut Grove, where he has been living in a $3.6 million condo in a luxury high-rise that affords panoramic views of yachts that crowd the shores of Biscayne Bay.

In July, OCCRP and Law&Crime reporters watched Zarrab as he paced the parking lot of the Park Grove condominiums, talking loudly on his cell phone in Turkish. After several circuits of the area — watched over by a trio of gold-colored statues of men in “See No Evil,” “Hear No Evil,” and “Speak No Evil” poses — he was whisked away in a chauffeur-driven Cadillac Escalade.

Turkey has already seized some of Zarrab’s assets, and he is expected to forfeit more to the U.S. when he is sentenced. That won’t happen until after the trial of Turkish state bank Halkbank, however, and it’s unclear when that will be. In the meantime, Zarrab can afford a lavish lifestyle — some of it funded by the wire transfers from Turkey.

“I’ve long been concerned with how the Justice Department handled this case, and the appearance of political interference on behalf of Turkey influencing the department’s decision-making,’’ said U.S. Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden.

“This was the largest sanctions-evasion scheme in U.S. history, and the possibility that the U.S. financial system is being used to facilitate improper transactions for Reza Zarrab and other co-conspirators implicated in the scheme deserves the immediate attention of U.S. officials.”

Two Zarrab defense attorneys — one of whom has allowed Zarrab to use his car and credit card — said their client is living up to his plea deal and “all material aspects” of his activities are known to the government.

Zarrab did not respond to interview requests made through his legal team.

The Zarrab Prosecution

Turkish-Iranian money launderer Reza Zarrab was arrested by FBI agents on March 19, 2016, at Miami International Airport, where he had just landed with his family while on vacation.

Ties to His Old Life

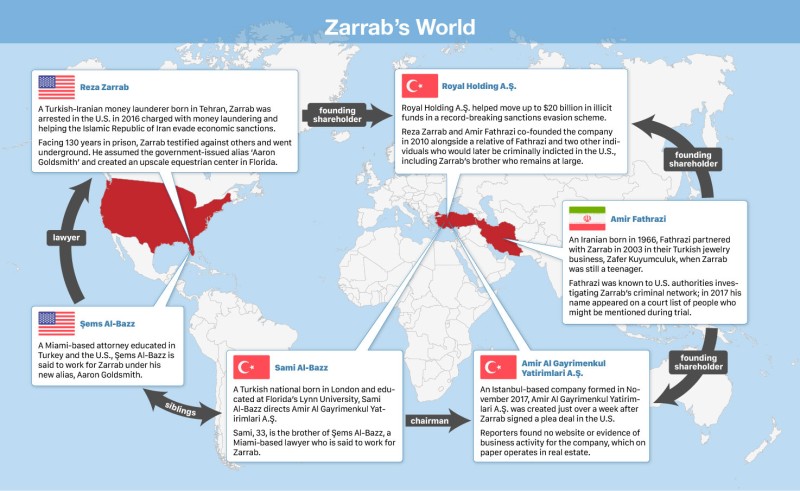

Just over a week after Zarrab’s 2017 plea deal, corporate records show that a key member of his inner circle, Iranian businessman Amir Fathrazi, started a new Turkish company.

Its founding chairman was Sami Al-Bazz, the brother of a Turkish lawyer who relocated to New York to help with Zarrab’s defense in December 2017. People familiar with the money launderer’s affairs say that lawyer, Şems Al-Bazz, now works as Zarrab’s personal administrative assistant in Miami. She did not respond to requests for comment.

Fathrazi was a shareholder in Royal Holding A.S., which Zarrab used to launder billions of dollars for Iran, and his family is closely aligned with Zarrab's.

OCCRP identified at least a dozen companies in Iran that involved Fathrazi, his father, or another relative as directors alongside members of Zarrab’s immediate family in Iranian corporate records. At least six are now active.

The new Turkish company, Amir Al Gayrimenkul Yatırımları Anonim şirketi, is on paper a real estate investment firm. But like dozens of shell firms Zarrab used to move illicit money, it shows no signs of real business activity. Only scant details of its business affairs appear in public records, and the company has no website or online presence.

Sami Al-Bazz told OCCRP that Zarrab has no connection to the business in Turkey.

“It’s just real estate, but I don’t want to comment about my business,” he said in a brief telephone conversation.

Multiple attempts to reach Fathrazi through his business and individually were unsuccessful.

Zarrab was still a teenager when he partnered with Fathrazi in 2003, according to records for their Turkish jewelry business, Zafer Kuyumculuk. Turkish law enforcement later identified one of its directors, Ertugrul Bozdoğan, as part of Zarrab’s criminal organization. He could not be reached for comment.

A decade later, in 2013, Fathrazi established a gold refining business in Iran with Zarrab's father, Hossein. Three months earlier the elder Zarrab had been fined $9.1 million by the U.S. in relation to a money exchange in the UAE, which prosecutors later identified as integral to Reza Zarrab’s money laundering scheme. Fathrazi was not charged in the Zarrab prosecution.

Peter Sprung, a retired assistant U.S. Attorney who handled complex criminal cases in the Southern District of New York, said Zarrab’s financial arrangements and apparent continued contact with former money laundering colleagues could cause big problems for prosecutors who plan to use him as a witness against Halkbank.

“If it emerged that Zarrab had acted dishonestly or fraudulently, or associated with known criminals, or even worse, committed a crime, it would seriously undermine his usefulness as a cooperator. Depending on how important he is to the [Halkbank] case, it could grievously harm that case,’’ Sprung said.

Zarrab himself could also face his full 130-year prison term and entirely new charges if the Department of Justice determines he has breached the terms of the deal, Sprung added.

Zarrab’s New York-based criminal defense attorney, Robert Anello, would say little about his client beyond rejecting any suggestion that Zarrab has been involved in improper dealings since his plea deal.

“All material aspects of what Mr. Zarrab has been doing the past couple of years ... have been known to the government,” Anello said.

“There have been some suggestions made of activity that you have characterized as money laundering or the like, and to the extent any such suggestion is made — it would be false, defamatory and obviously damaging to Mr. Zarrab.”

Follow the Money

Financial records obtained by OCCRP indicate that Zarrab’s Florida lifestyle and his horse business are being financed by international wire transfers from dubious companies and people in Turkey with no known connection to the money launderer.

In July 2020 a man in Turkey, Suat Aktas, wired $78,000 to the owner of Zarrab’s former rental home, who lives in Portugal. That wire passed through the Manhattan branch of Standard Chartered Bank, a British lender that processed more than $1.2 billion for 10 Zarrab-linked companies between 2007 and 2015.

Five days later, Aktas wired $10,000 on Zarrab’s behalf to a South Florida interior designer who decorated his condo and house in Davie, a town northwest of Miami. The interior designer said Zarrab identified himself by yet another name, John Kaplan, and said he was from Turkey. She said she dropped him as a client because he was slow to pay and “things just didn’t seem right.”

Aktas’ wires list two Istanbul addresses where he isn’t registered. He could not be further identified by OCCRP or located for comment.

Zarrab arranges even small payments directly from Turkey. In July 2020, for example, a Florida man Zarrab hired to transport horses received a $1,600 Western Union wire transfer initiated by Uğur Kolcu, an Istanbul-based accountant for an automotive company.

The following month, a man named Erhan Okcuoglu wired $3,350 from Turkey to Wellington, Florida horse trainer and riding coach Endel Ots, who confirmed that he had received the payment for riding lessons he provided to Zarrab’s former girlfriend.

Reached in Turkey, Okcuoglu said he doesn’t know Zarrab and never transferred him money. When pressed, he stopped replying to messages. OCCRP also contacted Kolcu through social media, but he immediately deleted his account.

When not paying with international wire transfers, Zarrab has used a high-limit platinum American Express card bearing the name Erich C. Ferrari, the attorney whose firm handles the sanctions violation portion of Zarrab’s defense. The Escalade Zarrab uses is also registered to Ferrari in Washington, DC.

“Mr. Zarrab is my client and my relationship with him is an attorney-client relationship, and not personal in nature,” the attorney said in a written statement. “Further, any financial arrangements between Mr. Zarrab and myself were proper and lawful, were in connection with my representation and/or to protect his safety, and the government is aware of them.”

Anello, Zarrab’s New York-based attorney, agreed with his colleague, saying: “There has been no financial impropriety and the government is aware of Mr. Ferrari’s representation of Mr. Zarrab and his assistance.”

The U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, which oversees Zarrab and the Halkbank prosecution, declined to comment.

But attorneys who were briefed by reporters about what’s known of Zarrab’s financial entanglement with Ferrari questioned its propriety.

Jennifer Rodgers, a former prosecutor in the Southern District of New York, said there can be legitimate reasons for a defense attorney to help a client with expenses, often adding it to their bill later. But she said the financial dealings involving Zarrab's lawyer appear to be “weird stuff" that suggests prosecutors were "not being as careful as they should be.”

“Maybe they were more lenient than they should have been in terms of letting him keep more than he should,’’ she said.

Sprung, who spent more than a decade in the Justice Department public integrity section, said the arrangement could come back to haunt Ferrari.

“When he [Ferrari] stands up and addresses the court, he's got to speak with authority and impartiality,” Sprung said. “If [Ferrari’s] getting involved in seemingly sketchy financial transactions with his client, then he's undermining his ability to do that.”

Reza Zarrab’s Legal Dramas

Comes A Horseman

Today Zarrab is living the good life. His picture for his WhatsApp account shows him prominently displaying a Richard Mille Swiss watch that sells for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

As of July this year, he was living in a Miami condominium designed by famed architect Rem Koolhaas and described in marketing materials as part of “an ultra-luxury condo building” with 12-foot-high ceilings, elegant bathrooms, and rooftop pool deck.

Zarrab’s three-bedroom unit has been offered to rent at $10,000 per month in the past and is now listed for sale at $3.65 million. Advertising by a Miami real estate agent shows multiple interior photos, including one in which a framed photo of Zarrab and his daughter is visible. The agent declined to say if Zarrab still lives there. The identity of its owner is shielded by a Florida limited liability company that bought it a few weeks before Zarrab was allowed to move to Florida in 2018.

Outside of the condo, much of Zarrab’s Florida life revolves around horses. Multiple racing association websites show he has ridden in several cross-country endurance races in the state and as far away as Montana, competing under the alias Richard Ferrari.

Zarrab has bought several horses in Florida, including Sonata MF, a sleek $300,000 show horse. In August, photographs showed Zarrab ringside when Sonata MF won a dressage national championship in an arena not far from Chicago.

Zarrab also is building a commercial stable complex in Davie. Property records show that in September 2020 a newly formed company, Pegasus Equestrian Davie, Inc., bought the five-acre Twin Horse Farm for $1.2 million.

Pegasus, recently renamed Next Level Performance Center, Inc., lists as president Aaron Goldsmith — Zarrab's government-approved alias. Its owner is not known.

Zarrab is now finishing a major, likely multimillion-dollar redevelopment of the old stables, adding a large covered arena with an attached office building, a 32-stall horse barn, and other high-end facilities. According to a news release from a public relations firm hired by Next Level Performance, the company “will also operate a world-class sales program featuring some of the best talented, young dressage and show jumping prospects in the country.”

Until recently, a sign at the entrance to the stables listed two contact numbers: Zarrab’s own cell phone and the number for a closed hookah bar in Springfield, Virginia, once operated by Manuchehr Negahban, a known friend of Zarrab’s family in Iran who relocated to Florida to oversee construction and serve as a Next Level company director. He did not respond to messages requesting comment.

OCCRP found no evidence of illicit dealings at Twin Horse Farm, which has yet to open for business. But the horse racing industry has long been used to launder criminal profits.

Unlike banks or other financial institutions, the equine industry is not required to have anti-money laundering compliance programs. And the value of a horse, like a fine painting or sculpture, is both highly subjective and easily manipulated to wash dirty funds.

Cecilia Farfán-Méndez, a University of California at San Diego researcher who studies drug trafficking and money laundering, said the large amounts of money involved, the ease of entering the industry and the difficulty of seizing animals as assets made horses an attractive prospect for people trying to conceal illicit funds.

“The equine industry, in particular those sections that are not regulated, are good options to launder money because there is a lot of cash and money that moves but they are not obligated [to follow anti-money laundering rules],” she said.

It’s unclear when Next Level Performance will begin business, though the stable’s Instagram page was recently updated to say “Opening in December.” When a Miami Herald reporter visited the future stable complex following Turkish media reports about Zarrab’s location in late October, a man at the closed front gate recorded potential visitors with his cell phone while shooing them away. New “no trespassing” signs were posted around the property.

Is That You, Reza?

Hiding In Plain Sight

OCCRP obtained a photo of a U.S. Employment Authorization card dated May 8, 2020. The card, issued by the Customs and Immigration Service and mailed to the FBI’s New York field office, bears a photo of Zarrab in blazer and tie with his actual birth date and true country of birth, Iran.

The name on the card: Aaron Goldsmith.

Florida issued a driver’s license to Aaron Goldsmith, and Zarrab used the name to open bank accounts and to incorporate his horse business.

Yet Zarrab does a poor job of hiding. The Cadillac Escalade registered to Erich Ferrari still bears the same District of Columbia license plates it had when a Turkish newspaper published photographs of Zarrab using it in New York City three years ago, making it easy to determine Aaron Goldsmith’s true identity.

Around Miami and in the horse world, Zarrab usually goes by the name Richard Ferrari. Zarrab listed what appears to be a combination of the two names, “Aaron Goldsmith (Richard),” on a recently deleted Facebook page that displayed photos of himself and several associates or employees at equestrian competitions. Among Aaron’s social media friends and Next Level Performance followers were a celebrity once engaged to Zarrab, his relatives, and associates in Turkey.

His true identity and his Richard Ferrari alias have also appeared in public records.

While keeping his Miami condo, Zarrab lived for eight months in Davie, sharing an upscale home with a 29-year-old professional horse trainer, whom OCCRP is not identifying for her safety. On May 13, 2021, the woman contacted Davie police to report that “she is concerned that something might happen to her because of Reza.”

The woman told officers she met the man she knew as Richard Ferrari in mid-2020. They were soon living together in a sprawling five-bedroom home with a pool on Jockey Circle, in the Woodbridge Ranches gated community a 10-minute walk from his stables.

The relationship soured in February when she “came across Reza’s personal identification and learned of his real name,” a Davie police officer wrote in a report. “She then did some research and learned Reza had been arrested in the past for money laundering and other charges.”

The officer put Zarrab’s true name, date of birth, and cell phone number in his report. Davie Police wouldn’t say if there was any follow-up investigation.

After the breakup and Zarrab’s move back to his Miami condo, the woman twice called police to Jockey Circle to investigate suspicious activity or noises, and told officers that she believed Zarrab was stalking her. She declined to comment for this article.

When Zarrab started Facebook accounts for Aaron Goldsmith and for the Next Level Performance Center in July, one of his first posts was a declaration that he was in a new relationship with a 22-year-old horse trainer. She did not respond to requests for comment.

Additional research by Sharad Vyas and Lara Dihmis of OCCRP, Jay Weaver of the Miami Herald, and Denise Hassanzade Ajiri.