The Caribbean island nation of Dominica may have sold thousands more citizenships to foreign buyers than it has publicly disclosed, research into the country’s budget figures shows.

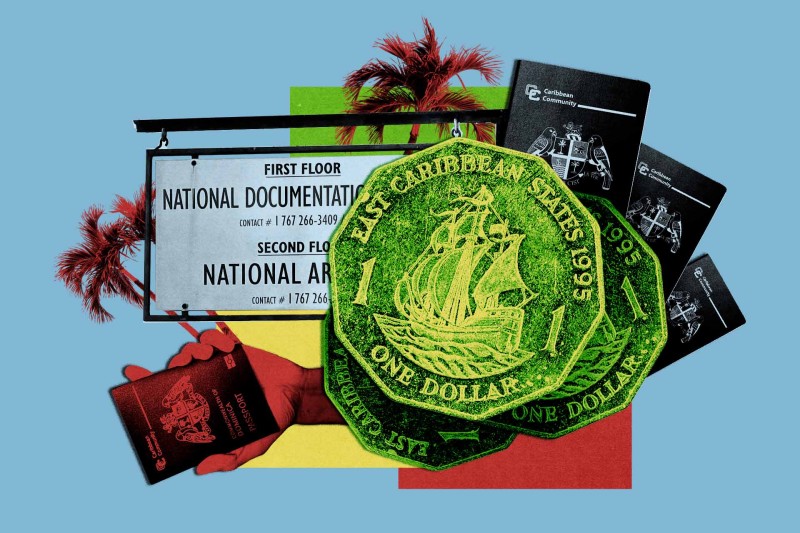

Reporting by OCCRP and partners, published this week as part of the Dominica: Passports of the Caribbean project, shed light for the first time on who has come to hold the country’s passport in recent years. The list includes oligarchs, officials from repressive regimes, and people who were later accused of crimes and became fugitives from the law. For a base price of $100,000, buyers get visa-free or “visa-on-arrival” access to much of the globe.

One of the world’s biggest citizenship-by-investment programs, the scheme made the island $1.2 billion between 2017 and 2020 alone, according to Dominica's government. A boon since its inception in the early 1990s, it now makes up a significant portion of state revenues.

But when reporters compared the names of new Dominicans published in the country’s weekly national gazettes with names uncovered in separate leaks, as well as with published budget figures, they found serious discrepancies that have not been explained by the government.

These show that, at best, the island’s reporting system may offer an incomplete picture of just who acquired Dominican nationality. At worst, the findings call into question the transparency of the program’s finances and whether islanders are benefiting to the degree they should.

The national gazettes, which span the years 2007 to 2022, include the names of roughly 7,700 new citizens. But a line item for naturalization in Dominica’s national budgets that covers the period from mid-2016 to mid-2022 suggests that the government collected enough naturalization fees to account for more than 19,000 new citizens in those years alone.

Missing Citizens

Dominica’s political opposition has long highlighted what it says is the government’s failure to release complete data on both the number of passports issued and the exact revenues raised.

Thomson Fontaine, leader of Dominica’s opposition United Workers Party and a former economist with the IMF, told OCCRP partner Heidi.news that the program “has exploded in the last 10 years,” but disparaged its “absolute lack of transparency.”

Sarah Kunz, a University of Essex sociology lecturer who researches the global citizenship industry and who reviewed reporters’ findings, told OCCRP that the sale of citizenship relies on secrecy. “CBI programs often sit outside democratic structures of governance, such as budgetary mechanisms,” she said.

“As with any valuable resource, the absence of democratic oversight and transparency over how many citizenships are sold, and to whom, enables abuse by governments, private sector intermediaries, and clients,” Kunz added.

Dominica’s government did not answer detailed, repeated questions on its citizenship numbers, and did not say whether it would publish the names of those individuals who do not appear in the gazettes.

Instead, in a press conference in which he addressed the upcoming reporting, Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit lashed out, without evidence, against what he said was an opposition-funded attack by international journalists bent on destroying the passport program.

Dominica’s citizenship-by-investment scheme “underwrites a significant part of our economic and social development [and] the full cost of the national employment program, close to $5 million every month,” Skerrit said in its defense. “[It] has been used to build thousands of homes, improve health care, help with national security.”

Gazette Gaps

Much of the available documentation in regard to passport buyers sits in Dominica’s National Archives in the capital of Roseau, a city of about 15,000 people made up of roughly a dozen square blocks filled with aqua, lime and pink colonial-era buildings.

At the archives visited by reporters, copies of weekly, string-bound government gazettes can be seen: thin magazines that name thousands of citizenship buyers.

Last year, the Government Accountability Project, a U.S.-based whistleblower and advocacy group, managed to procure dozens of these gazettes from a number of sources both inside and outside of Dominica. As well as libraries and private collections, many were obtained from the University of the West Indies Mona in Kingston, Jamaica.

The data was then provided to OCCRP and partners.

The gazette filings are meant to offer a comprehensive overview of new Dominicans.

“Dominica’s CBIU [Citizenship by Investment Unit] … publishes its economic citizens’ names in the official quarterly gazette and provides a detailed budget of where CBI funds are invested,” said a report from CS Global Partners, the official marketing promoter of the Dominican government.

But, aside from the discrepancies between the gazettes and Dominica’s published naturalization fee numbers, a review of several independent leaks containing Dominica passport information confirms that some names are missing.

These leaks contain over 100 individuals who obtained Dominica citizenships, but were not listed in the gazettes.

And for unexplained reasons, Dominica’s gazettes stopped publishing the names of new citizens in March 2019. Between then and December 2022 — the last gazette seen by reporters — the gazettes didn’t include the name of a single new passport holder. (It’s unclear if any new lists have been published since.)

Muddy Budgeting

Our reporting suggests that the number of people who acquired Dominican citizenship is considerably higher than what has been publicly disclosed.

But another line item in Dominica’s budget, which adds up the $100,000 base “investment” paid by each new citizen, cuts in the other direction: These revenue figures are considerably lower than expected.

Take for example the gazettes which show that 382 people acquired citizenship in 2010 and 2011. At a baseline price of $100,000 per investor, this could produce some $38 million in revenues. In reality, the true figure would be somewhat lower, because family members of primary applicants receive their citizenships at a discount.

But the citizenship revenues listed in the country’s budgets for that time are far lower than that. For the period between July 2009 and July 2012 — six months longer than those two years — they amount to just $15.6 million.

There are other reasons to question these figures. In 2011 and 2012, the national budget reported the exact same amount of passport program income down to the dollar, just over $6 million.

Jessica Tillipman, Associate Dean for Government Procurement Law Studies at George Washington University called that an unlikely coincidence.

“Anytime you come across an account anomaly like this, you need to stop and investigate further,” Tillipman said, calling the duplicate numbers a “red flag.”

More recently, Dominica’s government has also publicly contradicted itself on citizenship revenue.

In parliament, Prime Minister Skerrit said that between June 2018 and July 2019, Dominica sold just under 2,000 citizenships and had received about $170 million. But the national budget records just $80 million of passport revenue for the same time period. The gazettes, meanwhile, show almost 4,000 people obtaining citizenship between August and December 2018 –– about twice as many as Skerrit admitted to in parliament.

Kristin Surak, author of a new book The Golden Passport, said several countries have problems with how the revenues from their citizenship-by-investment programs are reported. Beyond smaller nations like Dominica, she said critics should also call into question other, bigger nations that also sell passports or visas, like the U.S. or Turkey.

“In a lot of countries, the data are not as clearly reported as they should be,” she said. “It can be challenging to get basic numbers and sometimes they don’t always add up.”

“It varies country to country, and it also varies over time,” she said, citing improvements in Malta, Grenada and St Lucia. “Compared to some other countries, Vanuatu and Dominica lean toward the ‘having issues’ side of the spectrum.”