Medical masks and protective equipment made by Uighur laborers in China are being sold across Europe by at least two major distributors, and have been bought by governments and health bodies in at least five countries, an investigation by OCCRP and partners has found.

The workers are ethnic Uighurs from the western Chinese region of Xinjiang who have been sent to factories in other parts of the country under a controversial “labor transfer” program that experts say is coercive and prone to abuses.

China’s government has embarked on a campaign to stamp out unrest among Uighurs in Xinjiang via a campaign of mass surveillance and detention.

The labor transfer program ostensibly provides Uighurs in Xinjiang with new opportunities to leave home for factory jobs in other provinces. But rights workers say they are often coerced into complying, amid a crackdown that has seen over a million Uighurs and other Muslim minorities sent to re-education camps. Campaigners have been pushing for Western companies and governments to stop buying products made with Uighur labor.

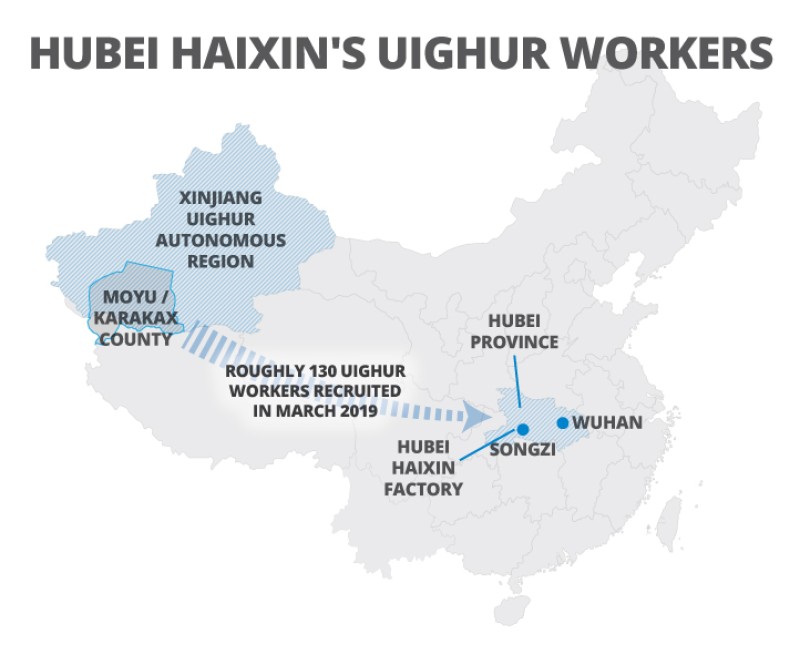

Earlier this year, the New York Times revealed that medical masks made by Uighurs at a factory in Hubei province were being sold in the U.S. Now, OCCRP and its partners have found that some of Europe’s biggest medical distributors are also selling masks and protective equipment from this manufacturer, Hubei Haixin Protective Products. Publicly available documents show that Hubei Haixin until recently employed at least 130 Uighur workers transferred from Xinjiang.

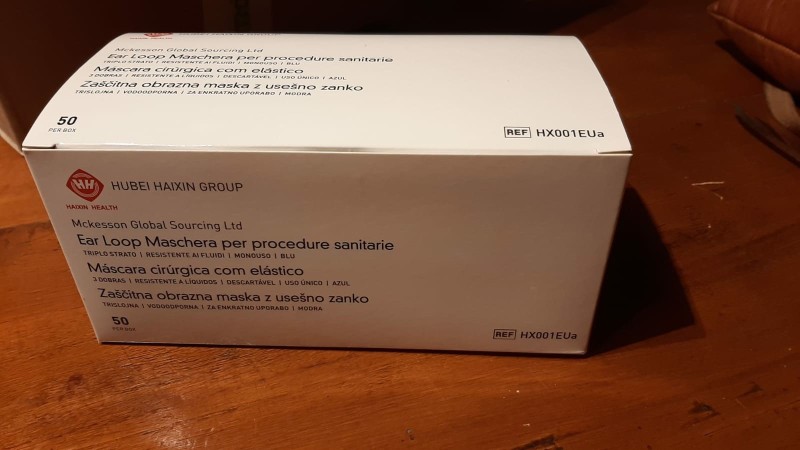

The distributors include local branches of McKesson, a multinational giant that owns some of Europe’s largest pharmacy chains and medical wholesalers, and Swedish medical supply firm OneMed, which sold masks to health authorities and national stockpiles across the Nordic and Baltic regions.

Both McKesson and OneMed continued selling Hubei Haixin products throughout 2020, even after the Chinese company was named earlier this year by the New York Times and a think tank, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), as using potentially forced labor by Uighurs.

Reporters also found McKesson and OneMed sold products made by Zhende Medical, a publicly traded Chinese company that has been flagged as risky by rights experts because it has supply chains and subsidiaries in Xinjiang.

In a brief response sent to reporters, McKesson Europe’s public affairs director, Ronan Brett, said: “McKesson Europe is committed to good corporate citizenship and ethical sourcing. Suppliers must agree to McKesson Sustainable Supply Chain Principles (MSSP) which covers compliance with appropriate laws along with adherence to our strict policies on protecting workers, preparing for emergencies, identifying and managing environmental risk, and protecting the environment.” He did not respond to a request for further comment.

OneMed’s head of operations, Robert Schmidt, said the company found out in late 2019 that the Hubei Haixin factory employed workers from Xinjiang, but continued its relationship with the producer after finding no evidence they were being coerced or mistreated.

"OneMed's overall assessment is that there is no forced labor or discrimination against the Uighur minority population in our supply chain,” he said. “But we will of course continue to follow the issue and act if we should receive any new information."

According to documents obtained by reporters, OneMed contacted Hubei Haixin with concerns about Uighur workers in January, and the Chinese factory promised to return them to their homes in Xinjiang at the end of their contract in March. But in reality, the factory continued to employ them until this September, claiming that pandemic movement restrictions prevented the workers from going home. OneMed continued buying the products.

Neither Hubei Haixin nor Zhende Medical responded to requests for comment, but in a statement sent to one of its European distributors, and obtained by reporters, Zhende said, “It is not acceptable in Zhende to engage in or support the use of forced or compulsory labor.”

“The so-called ‘human rights abuses’ in Xinjiang or ‘persecution of ethnic minorities’ are lies of the century made up by extremist anti-China forces,” a representative of the Chinese Embassy in Oslo, Yang Yiding, wrote in a statement to reporters.

China’s Foreign Ministry did not respond to requests for comment.

“Violation of Virtually Any Kind of Ethical Policy”

Over a million Uighurs and other Muslim minorities are believed to have been detained in newly built detention camps in recent years. China describes the camps as re-education facilities intended to combat Islamic radicalism, following a series of deadly inter-ethnic riots in Xinjiang and attacks by Uighur militants on ethnic-majority Han throughout China.

Uighurs have been documented working both in factories within Xinjiang’s detention camps, as well as being sent to regular factories throughout China via labor transfer programs, which are billed as a way of alleviating poverty and countering religious extremism.

But Adrian Zenz, an expert on China’s Uighur crackdown, said the labor transfer programs are rife with forced labor, “starting from recruitment to training in militarized closed settings, a highly coercive indoctrination and brainwashing, a very tight and matching transfer process that is closely supervised by government minders and cadres.”

Uighur workers sent to other parts of China often end up in “segregated dormitories that have cameras, that have guards, that they cannot leave at will,” Zenz said.

“And anybody who has any of that in their supply chain is in violation of virtually any kind of ethical policy, of ethical supply chain policies,” he said.

The use of Uighur labor by Hubei Haixin — which produces items such as masks, bandages and gowns distributed by both OneMed and McKesson — was first documented internationally in March by ASPI, the think tank.

Chinese reports describe the Uighur workers as earning an average of 2,800 yuan ($414) per month, relatively high by local factory wage standards. The women are housed separately, fed according to Uighur Muslim dietary customs, and taught Chinese, one news report said.

It cited one Uighur worker’s Chinese language class composition: “The water, soil, and air here are all very clean. In just 3 months, I’ve gone from being dark and skinny to paler and well-fed, and my skin is looking radiant!”

But international human rights and labor analysts are not sold on this rosy picture.

Given the crackdown in Xinjiang, and the widespread threat of detention, it’s impossible to be certain that the factory’s use of Uighur workers doesn’t involve coercion, said Penelope Kyritsis, the director of strategic research at the Worker Rights Consortium, an international labor rights monitoring group.

Any foreign company buying goods from a company like Hubei Haixin should act by “immediately ceasing its relationship with any companies that are located in Xinjiang and/or use inputs from Xinjiang,” Kyritsis said.

Zhende Medical, which sells to both McKesson and OneMed, is a less clear cut case, but experts say its supply chain is tainted with coerced labor.

Listed on the Shanghai stock exchange, Zhende Medical dwarfs Hubei Haixin in scale. In 2019 it was the country’s third highest exporter of medical goods, including medical dressings, masks, scrub suits, and compression stockings.

The company operates a Xinjiang-based subsidiary, but it also sources cotton and raw materials from Xinjiang, including from state-affiliated companies.

In response to questions, OneMed’s Schmidt told reporters that Zhende had sourced some components of wound care products from a factory in Xinjiang, but that Zhende claimed the raw cotton had been farmed in neighboring Kazakhstan and the United States. Zhende also told OneMed that the factory did not employ Uighur workers.

”There is a very strong and clear moral obligation by Western governments and companies to avoid companies like Zhende, which has both sourcing and manufacturing in Xinjiang. Full stop,” China expert Zenz said.

“We Take Responsibility for the Entire Value Chain”

Both McKesson and OneMed are major suppliers of medical and protective equipment to Europe, including some used in the battle against COVID-19.

Listed on the New York Stock Exchange, McKesson is a behemoth that earned over $200 billion in 2019. The company was tapped earlier this year by the U.S. government as a key distributor of COVID-19 vaccines. Its European division is run out of Stuttgart, Germany, and is active in 13 countries. The branch operates more than 100 distribution centers in Europe, and owns or co-owns thousands of pharmacies, including the international LloydsPharmacy chain.

Located in Stockholm’s affluent northern outskirts, OneMed is one of the largest distributors in northern Europe, operating across Scandinavia and the Baltic region.

McKesson has publicly committed to a “stance against forced and child labor” and its European operation asks its suppliers to agree to strict “Sustainable Supply Chain Principles.” OneMed, for its part, states online that it takes “responsibility for the entire value chain. We do this by ensuring that our products are produced under fair conditions."

Despite this, reporters were able to find multiple instances of McKesson and OneMed selling Uighur-made goods throughout Europe during the pandemic, even after Hubei Haixin’s use of Uighur workers became public record in March. (For complete details, see the graphic below.)

In some cases Hubei Haixin products formed a major part of national responses to the pandemic crisis, which in the early months of the outbreak saw panic buying and competition between countries.

Most strikingly, Hubei Haixin products imported by OneMed were among an airlift of 100,000 masks to Norway that was welcomed by the country’s prime minister, Erna Solberg, in March. The company ended up supplying at least a million masks and 2.3 million gowns to the country. Reporters also found Hubei Haixin goods were sold to governments and health bodies in neighboring Sweden, as well as Lithuania, Estonia and Denmark.

Reporters also found that both Hubei Haixin and Zhende products were sold online by OneMed, and were distributed and sold by several subsidiaries of McKesson. In Italy, reporters were able to order Hubei Haixin masks online from local McKesson company LloydsPharmacy, which arrived with packaging stating that they were imported by a U.K.-based subsidiary of the multinational. McKesson was also found to be distributing Hubei Haixin and Zhende products in Sweden, Norway, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

Louise Brown, a Sweden-based expert on corporate social responsibility and China, said that widespread human rights abuses and extremely limited access for independent auditors to assess local conditions make it unlikely that any buyer can ensure that suppliers in Xinjiang are not associated with forced labor.

”If a company chooses to source from Xinjiang region, it is a matter of judgment whether you are willing to risk actively supporting production involving human rights violations and forced labor, clearly against international recommendations. If you do, on what principles or corporate values is your business based?”

Sarunas Cerniauskas, Liucija Lenkauskaite, Anna-Klara Bankel, Mikkel Jensen, Alexander Hecklen, Martin Laine, Dennis Mijnheer, and Lars Bové contributed reporting.

This story was done in collaboration with SVT (Sweden), NRK (Norway), DR (Denmark), IRPIMedia (Italy), Follow the Money (Netherlands), De Tijd (Belgium), Eesti Päevaleht (Estonia), and Siena.lt (Lithuania).