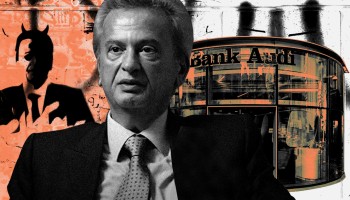

Offshore companies owned by the governor of the Central Bank of Lebanon have quietly invested in overseas assets worth nearly US$100 million in recent years, even as he has encouraged others to invest in his economically devastated country.

Rumors of Central Bank Governor Riad Salame’s offshore wealth have swirled around Beirut for years, but the extent of the investments by one of Lebanon’s most prominent public officials has remained secret — until now.

OCCRP and its Lebanese partner, Daraj.com, tracked Salame’s vast overseas investments, finding multiple real estate deals in the United Kingdom, Germany, and Belgium made over the course of a decade. Company accounts suggest the investments were often financed by borrowing, with tens of millions of euros in credit sometimes secured without collateral.

Much of his money went to the U.K., a favorite destination for overseas investors looking for a discreet place to make their money grow. Foreign corporations with undisclosed ownership now hold property valued at more than 84 billion pounds ($104 billion) in England and Wales, which has prompted calls for greater transparency in the U.K.

When contacted by OCCRP, Salame said he has broken no laws — that he amassed “significant private wealth” before he joined the central bank in 1993, and that “nothing prevents me from investing it.”

It’s unclear if the offshoring violates any Lebanese laws, but revelations about Salame’s investments come amid a financial crisis that many in Beirut blame on his management of the Banque du Liban (BdL). In a recent Financial Times analysis of leaked audit reports, the governor was accused of using dubious accounting measures to artificially boost the institution’s assets by at least $6 billion. Salame attributes any criticism to politics and a “systematic campaign” against him.

A group of Lebanese lawyers in July formally accused Salame of various violations of Lebanon’s penal code, including embezzlement of BdL assets and mismanagement of public funds. A judge has set an October hearing date. Salame’s assets, including properties and several vehicles, have been ordered frozen.

In an email to OCCRP, Salame described the lawsuit and decision as “groundless.”

Governor Under Fire

In Hamra, a bustling central business district near the American University of Beirut, newly installed heavy concrete blocks mounted with barbed wire signal a new normal. The wall around the Banque du Liban building protects a financial institution — and a man — now under public attack.

For nearly three decades, Salame was seen as a financial genius and undisputed guarantor of a robust Lebanese economy, a national hero often discussed as a candidate for the presidency.

That image has been tarnished in recent months.

“Riad Salame is a thief” and "down with the governor" are common themes among the countless slogans and caricatures sprayed on walls and windows across Beirut.

Raoul Nehme, Lebanon’s economy minister until this week, described Lebanon in July as a “failed state,” in reference to the ongoing economic crisis.

Anger boiled over into violent street scenes in central Beirut following last week’s devastating explosion of abandoned ammonium nitrate stored at the port. Protesters stormed government buildings and erected gallows to hang effigies of the president, the parliamentary speaker, and the leader of the Hezbollah military group and political party.

On Monday, Prime Minister Hassan Diab and his entire cabinet resigned. Salame, who is not a cabinet minister, remains in office.

But the port disaster is seen by many as only the latest outrage suffered by a country already grappling with an array of crises and an economic collapse blamed on endemic corruption and the negligence of ruling politicians.

In November, the World Bank warned that half the Lebanese population could fall into poverty. The crisis has triggered economic disarray, a first-ever sovereign debt default, yawning unemployment, and soaring food prices. The Lebanese pound has lost 70 percent of its value against the dollar since October. Street demonstrations have raged for months. Protesters hurl Molotov cocktails at banks and ATMs. Security forces respond with rubber bullets.

Among the complaints: Salame for years has backed bank loan policies that drove excessive government borrowing, leaving Lebanon unable to make crushing debt payments. When the economy collapsed in 2019, the country’s elites transferred their fortunes to offshore accounts as restrictions on transfers and withdrawals left ordinary people cut off from savings and struggling to survive. Alain Bifani, who resigned as director general of public finance in June, says that up to $6 billion has been “smuggled” out of Lebanon since the crisis began.

Lebanese prosecutors in January asked a central bank investigation commission to determine how much money had been sent to Switzerland since last October, and to determine whether the source of the funds was suspicious.

Salame launched an investigation but said nothing publicly about his own substantial wealth, safely invested in Europe well before the current crisis and the period covered by the probe.

Family Affairs

Just six days after the central bank’s investigation was announced, a Luxembourg company beneficially owned by Salame pocketed 11 million pounds ($14.3 million) through the sale of a core U.K. asset acquired in 2013.

The deal went unnoticed in Lebanon. Riad Salame’s name appeared nowhere in the land records.

For years, the central banker has been able to shield investments like this from public scrutiny, often by placing them in the names of close family members who manage companies on his behalf.

Other Salame investments are handled through companies incorporated in offshore jurisdictions that require little or no public disclosure of beneficial ownership.

One property reviewed by OCCRP involved both family and concealed beneficial ownership: A 3.5 million pound ($4.1 million) apartment in Broadwalk House, which overlooks Hyde Park near the Royal Albert Hall in one of London’s most enviable postcodes.

The spacious apartment made an impressive home for Nady Salame, the son of the bank governor, but the 26-year-old was not the legal owner of the apartment that he listed as his address in official documents in 2013.

The property was owned by Merrion Capital S.A., an obscure company registered in Panama that bought the luxury apartment early in 2010. This company’s real owners were hidden behind Panamanian subscribers — stand-ins who executed the articles of incorporation of thousands of companies on behalf of clients — and the founder of a Liechtenstein trust company, who was listed as Merrion Capital's director and president.

Nady Salame became a director of Broadwalk House Residents Ltd, the building’s management company, in 2014. He wasn’t the legal owner of the flat until January 2017, when the unmortgaged property was transferred into his name exactly a month after his 30th birthday.

Title transfer documents filed with the U.K.’s Land Registry show that Merrion Capital transferred the property on January 3, 2017, to Riad Salame, who signed a statement saying the transfer was “not for money or anything that has a monetary value.” Given that no money changed hands, the statement suggests that Merrion Capital was connected to Salame.

The following day Riad Salame transferred the property to his son. Merrion Capital was dissolved two months later.

OCCRP asked Riad Salame if he was the beneficial owner of Merrion Capital. He did not answer.

The property at Broadwalk House was not the only example of a mingling of assets between Salame and his son.

Beginning in 2011, Nady Salame was appointed as a director of several European investment companies. He approved a slew of property investments across Europe, including a prime office building in London’s legal district.

The real beneficiary of these deals was his father, Riad Salame, who invested tens of millions of euros in real estate opportunities in three European countries under his son’s signature.

Riad Salame’s ultimate interest in the deals is now public because Luxembourg in 2019 changed its previously opaque corporate registry law to comply with EU standards for disclosure of beneficial owners.

According to the Luxembourg registry, Riad Salame owns or controls three companies: BR 209 Invest S.A., Fulwood Invest S.a.r.l., and Stockwell Investissement S.A. Since 2011, his son has been a director of two of these Luxembourg companies, as well as five subsidiaries of BR 209 Invest in Luxembourg, Germany, and Belgium.

Nady Salame has experience in managing the wealth of high-net-worth individuals. Three years before he started handling deals for his father, he took a job with Crossbridge Capital, a London-based company started in 2008 by former members of Credit Suisse’s U.K. wealth management unit.

Crossbridge Capital had strong ties to Lebanon’s banking and business elite. Its founding shareholders included Nabil Aoun, former president of the Lebanese Broker Association. Rami El Nimer, chairman and general manager of Lebanon’s First National Bank (FNB), and Roland El Hraoui, another FNB shareholder, later invested in the firm. Banque Audi Suisse S.A., a Swiss subsidiary of Lebanon’s Bank Audi, invested in about 2016 and Philippe Sednaoui, the Swiss subsidiary’s CEO, became a director.

Nady Salame, then 21 and fresh from internships at Merrill Lynch, Credit Suisse, and Julius Baer, was among Crossbridge Capital’s early employees. Within three years he was credited with attracting 100 million pounds ($158 million) in assets to the firm’s $2 billion portfolio, according to a 2011 wealth management industry publication. The origin of these reported funds is not known.

Nady Salame was awarded a minority share in the company’s Maltese parent company, Crossbridge Capital (Holding) Co Ltd. He remains a shareholder, though he left the firm in 2015. Nady Salame declined to comment when contacted by OCCRP. Crossbridge Capital said in an email that “at no time was Mr. Riad Salame directly or indirectly responsible for any client assets.”

‘A Penchant For Secrecy’

While something of an international banking superstar, Riad Salame has been criticized for his management style. U.S. diplomatic cables made public by Wikileaks reveal deep concerns over the possibility that Salame might be elected president of Lebanon.

In a March 2007 cable, former U.S. Ambassador to Lebanon Jeffrey Feltman was critical of Salame's "penchant for secrecy and extralegal autonomy at the Central Bank, past closeness with Syrian leaders, unwillingness to disclose the amount of Lebanon's net foreign exchange reserves, and resistance to the oversight of an IMF program.”

Feltman concluded that “aspects of Salame's record may not bode well for a transparent presidency.”

Recently contacted by Daraj.com about these remarks, Feltman said only, “I prefer not to comment on information that was intended to be private.”

Presidential Aspirations

Salame never ran for president. Complaints about his secretive management increased after his name appeared in the Swiss Leaks, a cache of bank records made public in 2015 by an HSBC whistleblower.

The leak exposed his beneficial ownership of an account at HSBC’s private banking arm in Geneva. The account was registered to a British Virgin Islands company, Naranore Limited, and had a balance of nearly $4.6 million in 2006–2007.

Salame’s profession was listed as “Director de Merill Lynch a Paris,” though the files indicate Naranore’s Geneva account was opened in 2003, a decade after Salame left Merrill Lynch for the central bank.

Asked about the discrepancy, Salame said via email that the account was opened in 1989 — apparently a reference to a separate personal account, also exposed in Swiss Leaks, that he opened in 1988. Naranore did not even exist until 2003. He declined to answer additional questions about the account, saying only, “Your information is inaccurate.”

Swiss Leaks also revealed that Raja Salame, the governor’s younger brother, was the beneficial owner of an HSBC Geneva private account opened in early 2002.

That account belonged to Forry Associates Ltd, a company established in the British Virgin Islands in 2001. Forry’s account balance was more than $5.8 million in 2006–2007.

Both Naranore and Forry were owned by the same nominee shareholder, Nomihold Securities Inc. Both were administered by Mossack Fonseca, the infamous and now-defunct Panamanian company formation agent exposed in the 2016 leak of documents known as the Panama Papers.

In an email to OCCRP, Raja Salame said, “I own private businesses and investments in the real estate and hospitality sector, locally and internationally, using solely my own private funds.”

‘A Well-funded Private Investor’

Speculation about Riad Salame’s personal finances exploded earlier this year when Lebanese media outlets reported claims that his close associates helped move a massive fortune offshore.

The reports were based on a dossier said to have been compiled by Cristal Credit, a French business intelligence company.

Cristal Credit did not respond to OCCRP interview requests, but in press reports the company has denied any involvement in producing the dossier. While widely reported, the unsubstantiated dossier cannot be independently verified. Salame calls it “forged.”

But it is true that Riad Salame has invested a fortune offshore.

Described as a “well-funded private investor” by one business associate, Salame has spent the past decade snapping up investment opportunities across Europe.

By the end of 2018, the assets were valued at more than $94 million, according to balance sheets for Luxembourg companies controlled by Riad Salame. The assets have been acquired with borrowed money, reflected as liabilities, though the source of the funding is not revealed in company filings.

Appearing on television in Beirut on April 8, after the reputed Cristal Credit dossier went viral, Salame said his net worth was $23 million when he went to work for the central bank in 1993. He said that included earnings from his successful commercial banking career and inheritances in 1978 and 1982.

He didn’t address the offshore investments, and it’s unclear if the $94 million in investment assets are related to the $23 million he spoke of.

“As the law stipulates, I cannot engage in any [business] activity as I need to dedicate my time to my work as central bank governor,’’ he said in the interview with Lebanese broadcaster MTV. “I gave this money to people with expertise and people I trust who invested them over the last 27 years.”

The law in question is Article 20 of Lebanon’s Money and Credit Law, which states “The governor and his deputies are banned during their tenure to keep or to take any gains from a private company.”

“Gains” are defined as “any participation or membership in any form or manner even if it is a small loan.” The governor is allowed to hold a portfolio of securities issued by anonymous companies.

Ali Zbeeb, a Beirut-based lawyer and expert in international banking and financial regulation, said he believes Salame’s offshore investment violates the law and raises “suspicions over a Politically Exposed Person (PEP) holding such investments since it insinuates and reflects malicious intentions and attempts to hide actual sources of money.

“The Lebanese law is very clear and concise in terms of banning the governor and his deputies from engaging in any type of business and from having, acquiring or receiving or enjoying any benefits, which includes but not limited to offshore investments,” Zbeeb said.

Nizar Saghieh, a Lebanese lawyer and founder of the Legal Agenda, a Beirut-based law and public policy monitor, agreed with Zbeeb’s assessment.

“The mere fact of owning an offshore company in countries largely perceived as tax havens is in itself a suspicious act and raises questions about the intention behind making secret and opaque investments that are much lacking in transparency,’’ Saghieh said.

But Ibrahim Najjar, Lebanon’s former justice minister, told Daraj.com that he does not think Riad Salame violated Article 20 by offshoring his wealth. But he faults Salame for being too bullish about Lebanon’s economy when trying to win financial support from international investors and expatriates.

Concealed Interests

When it comes to business, Riad Salame’s identity and the relationship between his corporate interests are obscured in various ways.

Established in mid-2015 with a share capital of 5 million euros ($5.5 million), Stockwell Investissement S.A. looked like any other Luxembourg investment company. The profession of its sole shareholder, Riad Salame, was recorded only as “directeur de banque,” without naming the bank.

Four months later, Stockwell Investissement paid 6.38 million euros ($6.76 million) for upscale commercial properties and four parking spaces at Feilitzschstrasse 7-9 in Central Munich.

The firm made its second property investment in January 2017, paying 3.4 million euros ($3.64 million) for a retail property in Munich’s trendy Gärtnerplatz neighborhood.

At the end of 2018, Stockwell Investissement declared 14.4 million euros ($16.4 million) in current assets — almost all invested in securities, its balance sheet shows. Including the Munich properties, Stockwell Investissement’s total assets approached 24.2 million euros ($27.6 million).

Big as they are, Stockwell Investissement’s deals are eclipsed by those of Fulwood Invest S.a.r.l., a Luxembourg company owned by Riad Salame, whose involvement was first disclosed in 2019 when the country’s law on beneficial ownership changed. Until then, company documents showed only its directors, including Nady Salame and Marwan Issa El Khoury, Riad Salame’s nephew.

Nady Salame and El Khoury each manage several investment companies now known to be beneficially owned by Riad Salame. Together, they hid the governor’s involvement through Fulwood Invest in more than 30.8 million pounds (about $39.15 million) in U.K. commercial property investments.

The investments included Fulwood House, a prime office building in the heart of London’s legal district acquired in 2012 for 5.9 million pounds ($9.44 million), and an office building in Bristol for which Fulwood Invest paid 10.5 million pounds (nearly $16 million) in 2013.

Both deals were approved by Nady Salame, as was the purchase of a seven-story commercial property in Leeds for just over 10 million pounds (about $16 million) in November 2013. The company also bought an office building in Birmingham for 5.45 million pounds (almost $6.9 million) in 2016.

In January the company sold the Leeds property, with El Khoury signing off on the 11-million-pound ($14.3 million) deal.

Stockwell Investissement is linked to other Salame family investments through its manager, Gabriel Jean, the Belgian owner of CFT Consulting, an audit firm in Luxembourg. Before Stockwell Investissement, Jean also managed another company with ties to the family, Bet S.A.

Established in early 2007, Bet S.A. owned 99 percent of ZEL, a French property investment company. Riad Salame’s brother, Raja, was ZEL’s sole director, owning 1 percent.

Records show ZEL bought property worth 2.4 million euros ($3.23 million) in Paris’ posh 16th arrondissement, but ZEL shareholder’s filings suggest the deal was just a fraction of its investment activity.

Over several years starting in 2007, Bet S.A. loaned millions of euros to ZEL. During Raja Salame’s eight years as ZEL’s sole director, the total ballooned to 17.2 million euros ($18.8 million). With interest, ZEL came to owe its parent company more than 20 million euros ($22 million) by 2015.

The purpose of this funding was not disclosed in available filings but ZEL’s legal form suggests it was for investment in property assets.

Riad Salame never held shares, directly or indirectly, in Bet S.A. or ZEL. Raja Salame, in an email to OCCRP, called himself a “completely independent investor” who owns companies “using solely my own private funds.”

Continental Operations

Running almost 3 kilometers from central Brussels to Bois de la Cambre park, Avenue Louise is lined with Art Nouveau buildings, embassies, and shops selling luxury fashion brands. That’s where a subsidiary of one of Riad Salame’s Luxembourg companies saw money to be made in 2012.

“[We] received a very fair offer from a well funded private investor,” Ardstone Capital, a European property investment management company, said in a news release about the sale of a seven-story building on the Brussels thoroughfare. “It was sold to a private Middle Eastern buyer.”

The sale price was about 8 million euros ($9.5 million), Ardstone said.

The buyers were Louise 209A 1 and Louise 209A 2, Belgian companies created a few months earlier with Nady Salame and El Khoury as directors. The real beneficiary of both companies was Riad Salame, though his name appeared nowhere in company documents.

The companies’ shares were owned by BR 209 Invest S.A., a Luxembourg firm beneficially owned by Riad Salame but directly owned by Cometec S.A., another Luxembourg company that shared an address with BR209 Invest and was managed by employees of an audit firm.

On its website, Ardstone shows another transaction linked to Riad Salame.

Speditionstrasse 13a is a striking red-brick office building in a sought-after commercial redevelopment area in Dusseldorf’s traditional Rhine River docks.

The property was acquired for 4.85 million euros ($6.3 million) “on behalf of a private client,” according to an Ardstone news release in October 2012. Ardstone also said it had acquired Fulwood House in London on behalf of the same private client. That was the year Riad Salame’s Fulwood Invest bought Fulwood House. Ardstone declined comment for this story.

The Dusseldorf building appears linked to Dock 13-Villa GmbH, a Germany company first established in 2005 by a Swiss real estate investment company.

In 2012, 94 percent of shares in Dock 13-Villa GmbH were acquired by BR 209 Invest. Nady Salame and El Khoury acquired the remainder.

Dock 13-Villa GmbH’s latest balance sheet shows total assets of 4.03 million euros ($4.7 million), of which 3.12 million euros ($3.6 million) are fixed assets.

BR 209 Invest is also majority shareholder in H-Invest GmbH, another German company directed by Nady Salame. H-Invest GmbH’s most recent balance sheet lists total assets of more than 8.9 million euros ($10 million).

Accounts for BR 209 Invest made up to December 2018 suggest that the company has secured tens of millions of euros in credit without putting up collateral on the loans. The source of the financing was not disclosed.

Offshore Associates

Marianne Houwayek has been a public figure in Beirut since 2007, when the one-time Miss Lebanon runner-up was appointed to lead Salame’s Executive Office at age 27.

Described by the Lebanaese lifestyle publication Official Bespoke as Salame’s “right hand” and “protégée,” Houwayek landed the prestigious post after an internship at the central bank. Her stated responsibilities included “any specific task upon the request of his Excellency.” In April, Salame announced Houwayek’s appointment as his senior executive adviser, a position specially created to implement “any project the governor finds suitable.”

The purported Cristal Credit dossier claims that Houwayek helped Salame offshore a massive fortune to private banks in Switzerland and Liechtenstein. In an email to OCCRP, Houwayek called the dossier a “fabricated false report.”

But Houwayek has been involved in other offshore financial activity. Documents leaked in the Panama Papers seen by OCCRP and Daraj.com reveal that she was sole shareholder of Rise Invest S.A., a company formed in Panama late in 2011.

Rise Invest was designed to be secretive. The company issued bearer shares, a type of equity security that allows the owner to remain anonymous. The practice has since been banned in Panama.

One month after Rise Invest’s incorporation, Houwayek was granted general power of attorney. Weeks later, Rise Invest authorized the opening of an account with the Geneva branch of Banca della Svizzera Italiana (BSI), a Swiss private bank. Minutes of a company meeting in Panama on February 17, 2012, show Houwayek was to have “sole discretion” over the account.

The leaked documents don’t show a balance or purpose for the account, but such accounts typically require a minimum deposit equaling hundreds of thousands of dollars, a Zurich-based banker told OCCRP. By contrast, Houwayek recently disclosed that her monthly central bank salary was “not more than 12 million Lebanese pounds,” or about $8,000 per month.

The Swiss bank account has never been declared by BdL as part of Houwayek’s official duties or those of the Executive Office, nor has she publicly disclosed her connection to any Swiss private banking assets

An unsigned Rise Invest document submitted in 2011 to Mossack Fonseca said the company’s purpose was “holding of shares.” Houwayek later signed a statement describing the company’s activity as a “personal holding company holding my investments in bonds and shares.”

In an email to OCCRP, Houwayek said she reported her ownership of Rise Invest to BdL in 2012, and that “my personal wealth is from my family and my own resources.”

The leaked documents show that Rise Invest’s bearer shares were reported “lost or destroyed” in 2015 and a new share certificate was issued in Houwayek’s name.

The company remains active, but the status of its Swiss account is unclear. BSI was taken over by another Swiss bank, EFG International, following a criminal investigation in 2016.

Houwayek’s husband, Alexandros Andrianopoulos, is the founder of Onima, a high-end restaurant in London’s Mayfair neighborhood. Onima promises diners “five dimensions of pleasure” in a venue that includes a private members’ club and a rooftop terrace.

Lemonthree Limited, a U.K.-registered company, appears to stand behind the restaurant. Documents filed with U.K.’s Companies House list Houwayek as a “person of significant control” over Lemonthree, while another document filed in 2018 shows she and Andrianopoulos each owned half of the company.

Despite this, Houwayek denied holding any interest in Lemonthree.

“I do not have any business activity outside Lebanon including my husband's business,” she wrote in an email.

As of late 2018, Lemonthree’s total assets, less current liabilities, topped 1.8 million pounds ($2.36 million), according to unaudited accounts approved by Andrianopoulos. The company also reports a bank loan of 4.2 million pounds ($5.4 million). Company documents do not specify the terms or the lender.

Houwayek was not the only senior colleague of Riad Salame named in the 2016 Panama Papers leak. Saad Andary, second vice-governor to Salame from 2009 to 2019, was revealed as a shareholder in Finavestment Holdings S.A., a British Virgin Islands company.

Under Lebanese law, the central bank governor’s deputies are also prohibited from holding interests in private companies. Andary did not respond to OCCRP requests for comment.

A Call For Transparency

Greater transparency of property ownership in the U.K. is seen by civil society activists as one of the most urgent reforms needed to prevent financial crime.

Like Luxembourg, the U.K. has in recent years introduced a register of beneficial owners of companies. In 2019 it committed to a similar public register for real owners of U.K. properties.

More than 96,000 properties in England and Wales are owned by overseas companies, according to data published by Her Majesty’s Land Registry in July. The names of the ultimate owners of these properties are not published.

Many of the corporations are domiciled in tax havens like Panama and British Virgin Islands, where no ownership information is available. Many others are registered in low-transparency jurisdictions like Luxembourg that are only now beginning to open up.

While providing secrecy, offshore ownership can also enable financial crime such as money laundering and tax evasion — one of the key reasons behind campaigns to open up information on ownership in the U.K.’s property sector.

"The ability to acquire U.K. property anonymously is one of the main reasons Britain, especially London, is a destination of choice for those seeking to conceal their assets," said Ben Cowdock of Transparency International U.K.

Last December, in the Queen’s Speech to parliament, she proposed legislation that would close the loophole allowing anonymous companies to own property by introducing a public register of beneficial ownership.

<STRONG>This story drew on data from the Panama Papers, a set of documents that were leaked from an offshore services provider called Mossack Fonseca to the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ).</STRONG>